On June 17, Health Canada finally decommissioned the COVID Alert app. Launched nearly two years ago, the digital contact-tracing app was supposed to be an important way to keep ourselves and those around us safe from COVID-19, but that’s not how it played out in practice.

Since its launch, stories of its low adoption have been common, but so have deeper questions around whether it was ever an effective public health response. In April, Digital Public partner Bianca Wylie was already calling for the app to be shut down since provinces had curtailed access to PCR testing in the midst of the Omicron wave. Effectiveness aside, it could no longer even work as it was envisioned. But where does it go from here?

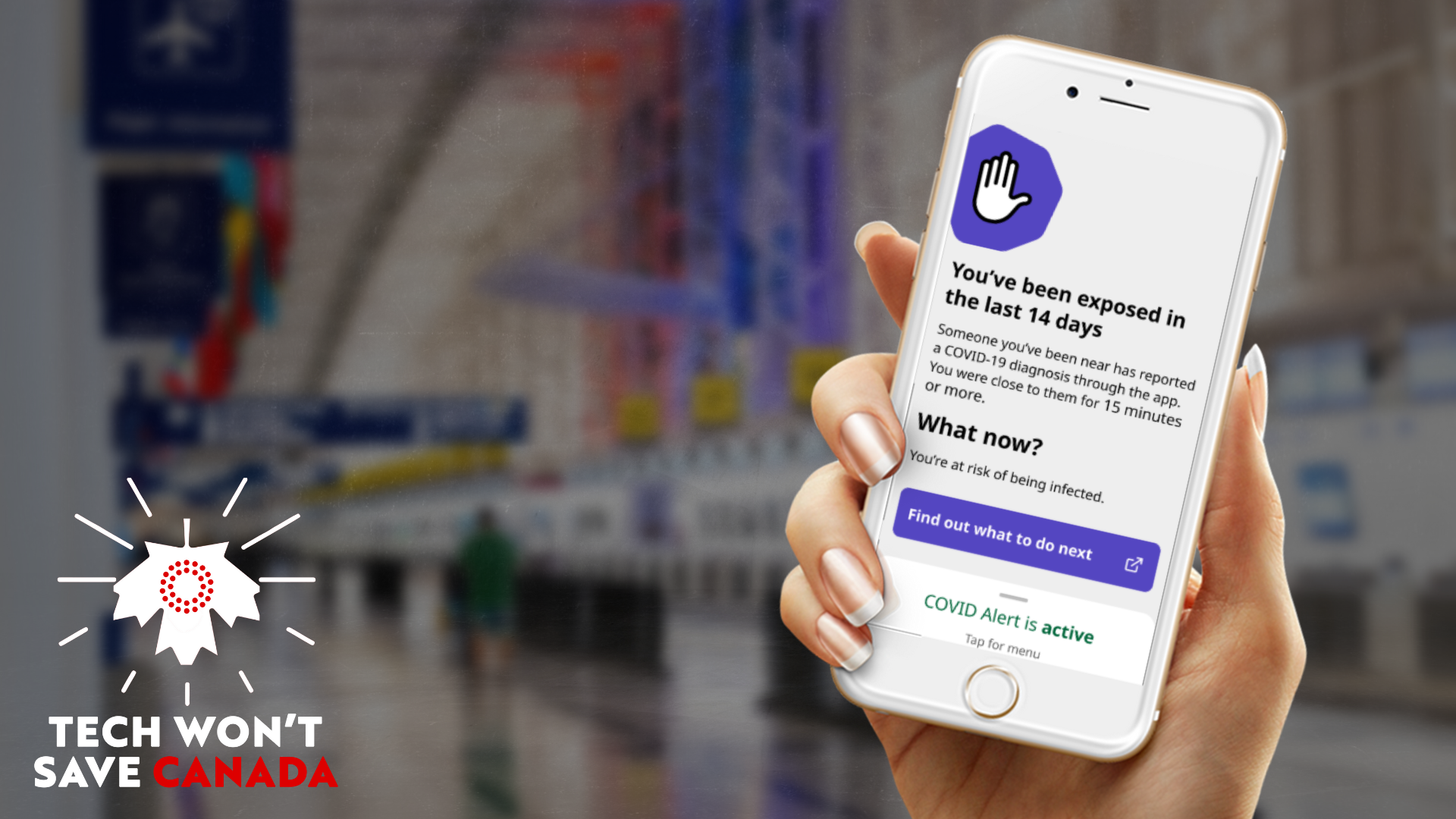

I host a podcast called Tech Won’t Save Us that provides a critical look at the tech industry. It usually has a pretty international perspective, and given that Silicon Valley is in the United States, it focuses a lot on what happens south of the border. But I wanted to do some more digging into tech issues in Canada, so I’m teaming up with Passage on a new monthly series on Canadian tech called Tech Won’t Save Canada.

The idea is simple: have critical conversations with experts on tech issues that are important to what’s going on in Canada. To kick it off, I spoke to Wylie about COVID Alert and what it would actually mean to learn the lessons of what she calls “an experiment done within Canada during a public health crisis.” The full interview can be found on my podcast, but below you’ll find an edited transcript of our conversation focusing on some of Wylie’s key points.

Paris Marx: On June 17, Health Canada finally shut it down and decommissioned COVID Alert. What did you make of that moment? Do you think that happened at the right time?

Bianca Wylie: It is significant that it happened because they could have got away with not decommissioning it. Seeing a government move through that cycle of launching something, maintaining it and then shutting it down means that there is a lot to learn.

In terms of timing, it was late. There are different points, which we can look at, where it likely could have been decommissioned. We can talk about the details of it, but I want to really stress that it’s significant [that it] happened, and it’s great that it happened.

PM: What are you seeing in the statements from Health Canada and in the final Advisory Council report that is standing out to you in terms of how the app is being framed, and how they are trying to have us think about the impact of it?

BW: The framing of the Advisory Council’s final report is really that this is a good idea. It’s good we did it, and then here are the minor tweaks and adjustments. I think that’s, just as a starting point, an incredibly incorrect read.

To me, you come out of this, and you own it, and you say, “This didn’t work.” You can see that the capacity for the government to decommission it is there, but on terms that actually tell a different story than the one that we really should be talking about, which is, “This didn’t work, these are some of the reasons why, so let’s look at those.”

It’s important that we make space for all opinions here. If someone really feels this is something that we should do in the future, let’s look at the pieces of it that didn’t work on a technical level. But it’s just as important for us in our society and our culture, to hold space for the idea that these types of things don’t belong in our public health responses in the future.

If there is one message you hear over and over from across the board in public health, it’s that this is a collective undertaking. And if we hold that truth, which is very important, against the kind of technology that this is, which is an individualistic on-your-phone app, I think it’s reasonable that we should say: this kind of tech does not align with the general precepts of public health. It just doesn’t.

If we want to consider mitigating them and thinking about how we might look at this discussion the next time it rolls around, that’s fine. But I just want to say as a general frame, this report does not say, “This doesn’t work. We are not going to proceed with more of these in the future.” If I would see that high level lessons learned, that’s when my trust starts to increase in government.

PM: I was in Newfoundland and Labrador, which was part of a group of provinces that took a different approach. We did have COVID Alert, but we shut down our borders for much of the early part of the pandemic in order to stop the virus. It was very well recognized that the human contract tracers were essential to keeping us safe, and to finding and identifying those cases that did breach the border restrictions. I don’t know if it existed the same way outside of the few provinces in the Atlantic part of the country.

BW: I keep coming back to this, of this emotional place that we’ve been in and continue to be in — exhausted, grieving, so many things — and the idea that we should be supplanting or switching how we work together and support each other in a really hard moment.

Not just the reduction in the labour and the quality, but the experience of that, and what it means to have no one hold your hand when you’re getting scary news that may then have these knock on effects where you need a wraparound of someone to tell you, “Okay, here’s what you do on this front. Here’s the kind of supports you can have over here. Oh, there’s children in your home. Here’s the thing about this.” You think about what it means to be supported by another person who’s trained to do that work. It’s so important. Losing that piece of it, which is different and related to efficacy, is really dangerous.

What did it mean to flood the province of Ontario with people who were getting these notifications, which were based on science that had already evolved on distancing, vaccines masks, transmission? There were so many things that had shifted, and it’s sending these notifications out. There’s a human impact when you get that notification. But on a systems level, what did it mean that you had people who were taking those tests that for the most part might not have needed to take those tests?

The last thing I want to say on this is something about the influence and impact of industry and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. The people involved in pushing this were really pushing it from an economic development perspective. While we know our whole response to the pandemic has been trying to keep the economy going, no matter the costs, we also need to add this into that frame, which is that this appeared on the scene because Google and Apple had an interest in showing up and saying, ‘Hey, we’re in a lot of people’s phones. What do we have to do here? How do we participate?’ That didn’t come from any of us. That didn’t come from a history of working.

It’s an easy thing for the government to skip over because you’ve got Health Canada talking, but who’s acting? Where did this come from? What does it mean that Shopify is there saying, ‘Hey, want some code?’ What does that mean for procurement? We just have people donate things, and then because they’re free, we’re going to use them for an experiment in the middle of a pandemic?

Honestly, some of these pieces, they don’t snap into each other very easily, but it doesn’t feel right not to acknowledge that the pressure to do this, and the ongoing pressure to do this, again, is coming from industry.

PM: You’ve been saying that what we really need is a public post-mortem of the app that really dives into the impacts that it has had. What should the focus of that post-mortem look like? And what is the risk if it doesn’t happen?

BW: We could think about a policy framework that is based on a life cycle of a technology. There are probably two or three really critical components of what the framework you need to have in place looks like before you launch an app like this.

The first thing has a lot to do with, “Do we do this or not?” I know it was going fast. I know people wanted to try something. I know they were hopeful. That’s all fine. But you still cannot be ahistorical. You have to say, “Okay, hold on. What’s happened so far? These are the potential risks. Let’s look at the trade offs.” And have a very clear way to have that conversation.

Instead of that, what happened with this app was ‘as long as it’s privacy preserving, let’s go.’ That cannot be repeated because efficacy was not discussed — and efficacy absolutely has to be there. Efficacy and privacy have a relationship to each other, particularly if we’re going to talk about public health, where, and I need to be very clear in this, I don’t believe this type of an approach in any circumstance is a good idea, these personalized apps. That’s me — one person — really, who cares about that?

Then, before you get out of there, you have to publish your benchmarks for when you will shut it down or change it or adapt it before you launch it. Because if you don’t do it before you launch it, you will always have a story to tell as to why you should just keep trying or changing or evolving or adapting. This is called path dependency. It’s very difficult if you don’t set that up at the beginning to stick to it.

Following launch, should the decision be made to launch something, you get into maintenance mode and tracking. This is where it is so critical to have this be public: public benchmarks, public publishing of all the things. Not the data that confused us, which is what happened this time.

The numbers we were given were how many people downloaded the app and how many people uploaded a one time key. Neither of those numbers tell us what the app did for our COVID response. They just say whether people downloaded tech. I feel silly looking back at it that I didn’t pop to the like, “Wait a second, this doesn’t even tell us anything.”

The real third chunk is around the shutdown process, and really messaging that clearly so that the government knows it’s okay to shut it down. I’m glad to end on that note because that did happen here. We have very capable people working in technology in the government. This was a difficult thing to watch, knowing that there were really good people who — as technologists — would know this thing should not be here anymore. So at least it’s this proof we can decommission something. It can happen. The world doesn’t fall apart, because we said we’d try something and it failed, no problem.

The only other thing, which is separate, is to do a proper post-mortem because this story is not getting at what actually happened in the ways that we need to think about efficacy and taking this stuff seriously. The government is sticking with this story from the beginning right to the end. And that is not helpful for us to work in real terms in public health with real information. This so far looks like a political undertaking of a lessons learned.

I would suggest we do a proper public post-mortem, driven by the public, and sharing lessons from other places in the world, because some of these things in here are true. Yes, the provinces needed to be held accountable. Yes, there were problems there. But you could have known those things without an app.

What we’re gonna get from the government is not going to be expansive, and it’s not going to get into those issues that we touched on because they don’t track with what the rhetoric is here: that this is a good thing, we just need to try a bit harder next time. Absolutely not.

I’m not saying that it shouldn’t be on the table. But if we want to have a proper conversation about it, we have to be able to say that this didn’t work. So one track is not doing these kinds of technologies again. And if you want to try it again, that’s when we go down that road of, well, what do we put in front? What’s the framework? What’s the maintenance? And what’s the shutdown plan?

PM: What does this whole experiment, this whole saga, tell us about tech governance in Canada, and how the government approaches technology?

BW: What this says about our government to me is ideologically it is pro-technology. It is pro-technology as an economy. It is a way that it wants to be seen. I think this entire app, you could look at it as a public relations campaign to say, “Hey, look at us, we’re doing new, innovative things,” which captures imaginations around the world. This is a long, big problem.

The way that it intersects with holding governments accountable is something that we need to hive off and get out of the technical privacy conversation and get into the like, “No, there’s actually a misalignment here.” If you’re going to be pro-technology, you’re never going to be able to align with what good technology standards look like.

We’ve got ArriveCAN, which is this mandatory app, which is a big problem and different than the COVID Alert one, which was voluntary. We are somehow trying to normalize the idea that for major events like travel or entry and exit to a country, much like public health response in a pandemic, engaging with an app on your phone is an appropriate way to manage such an interaction. We have to keep an eye on that, because we’re creating norms around things that are not actually beneficial to us.

If we don’t challenge that, you can see how the ratchet happens. We can see the enthusiasm for technology, we can see it being applied in different ways and trying just to keep ratcheting it up and normalizing. We don’t have a place to challenge these things in terms other than “go with it or you’re against the technology.” It’s like, no, no, no, we have ways to invest in people, and we have ways to invest in our services to pull off the same outcomes, in terms of like, coming in and out of a country or supporting people during a public health crisis. They do not require apps; they just don’t.

If I think about this too long, it’s pretty dark; this stuff isn’t good. It’s just not good technology, even if it’s deployed properly or accurately or it functions. We need to figure out how to move the priority investments into what we know works. But that’s a long fight. People have been trying to fight for that in so many different ways for so long, and we just have to realize that we need the shared language to challenge this without getting mired in the privacy or efficacy or whatever else.

Even if you think these things are good and they work, that’s not the only approach to our society and culture. We have to protect the space to say, even if they do work, “We don’t want that to be the way that this country operates. We just don’t want it.”

This interview has been edited by Paris Marx for clarity and length.