With Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s minority government recently threatened by the possibility of a Conservative-led non-confidence motion, Canada could be thrust into another election and, with that, an onslaught of campaign ads that will damage the country. We need to prep for what that entails before it gets here.

We all witnessed the carnage caused by the Leave.EU Campaign — championed by prominent conservative politicians — gaming Facebook and Twitter ad platforms in the 2016 Brexit Plebiscite, and Cambridge Analytica doing the same in the 2016 United States election. Both groups microtargeted Facebook users and served them appealing yet incendiary and outright false messages to scare them into voting either Leave or for Donald Trump. Some alleged that these campaigns fundamentally broke the political trajectory of two of the most powerful democracies in the world.

These events proved people are susceptible to out and out propaganda, but also something more sinister: Social media ads are a lawless hellmare where anyone with enough money can essentially buy the eyeballs and emotions of a significant proportion of the electorate.

Steven Bannon, a former board member of Cambridge Analytica and Trump election chief, has given credence to the often floated, though unproven and much criticized, theory that Brexit was ensured by the consulting firm’s approach to microtargeting. Its effectiveness, Bannon claims, led them to immediately roll it out to take Trump’s bid for president from a punchline to a success.

In March 2018, the New York Times published a damning exposé on Cambridge Analytica’s fraud. The firm’s data architect, Christopher Wylie, told the paper that Cambridge Analytica wasn’t concerned with legality, but only with winning for its clients. Wylie noted that the firm pursued its goals by displaying ads that played on voters’ worst fears, which were mined from their “likes” and other interactions on Facebook. It was the equivalent of someone reading your diary, and then manipulating you with that information without you even being conscious of what was taking place.

If you think Canada is immune to this type of interference, you’re wrong. It already happened, to an extent, in the last Ontario provincial election through Ontario Proud, which touts itself as a grassroots organization representing “the people” but is actually run by a former Conservative party staffer and funded primarily by developers and lobbyists.

Ontario Proud sought to hide these associations until they were made public, often trading in a fake ‘folksy’ veneer, but in reality pushing talking points favourable to those who were investing money. Developers who wanted to open up the protected Green Belt, for instance, were primary beneficiaries of Ontario Proud’s consistent ‘climate skeptical’ focus.

More recently, the Ontario government touted the support of many parents and teachers against the ongoing teachers’ strike. However, this support was actually coming from proxies closely tied to the Ontario government. The deception was exposed by reporters, but as of yet no one has been censured or punished for these schemes. We’re conditioned to expect this kind of outright propaganda.

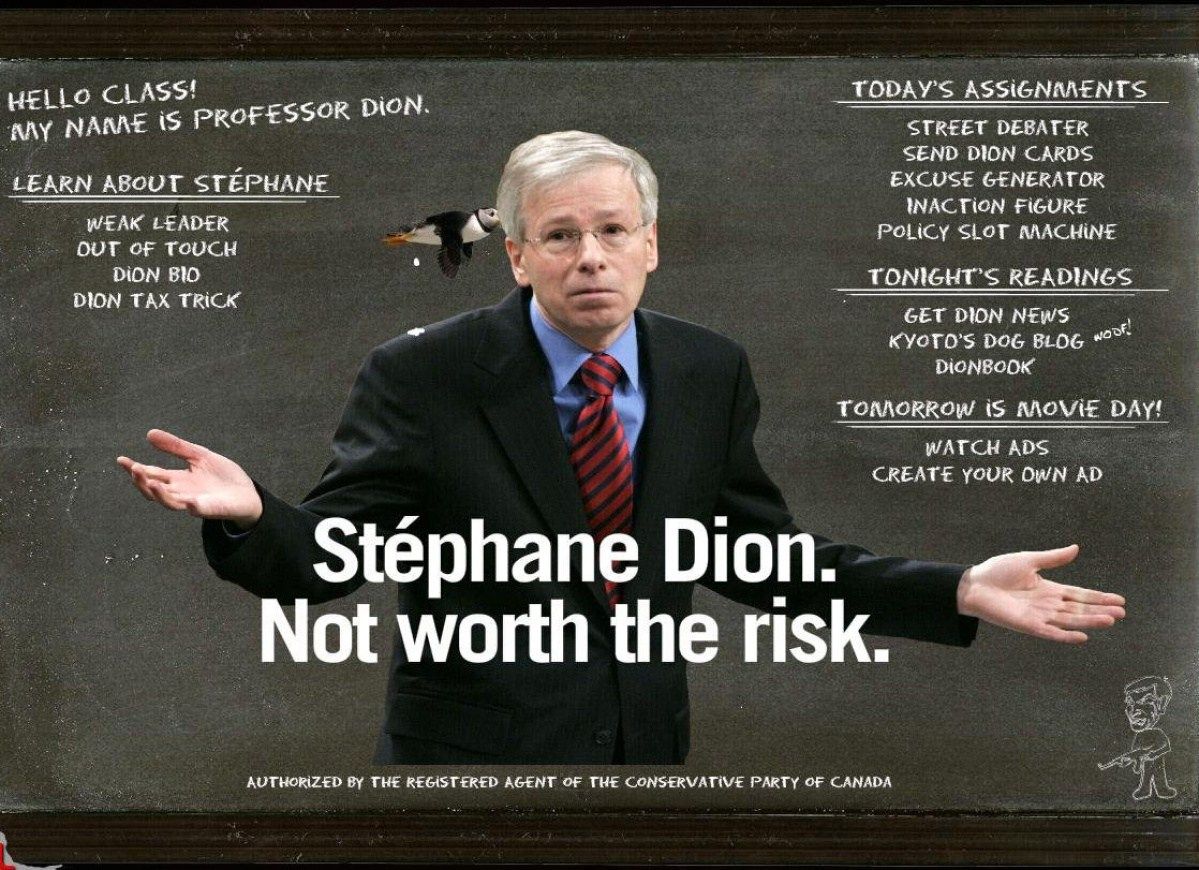

TV ads, while more of a firehose than a laser-sighted gun when it comes to targeting, are no less terrible, and are incredibly unnecessary. We need only look at Canada’s history of negative ads for proof, including such examples as the Jean Chrétien face ad, where his childhood Bell’s Palsy effects were played for laughs, or the Stéphane Dion attack ad, which focused on his sometimes halting speech patterns in English.

If election ads were just about mocking opponents for gaffes or flip flopping on an issue, they wouldn’t be so bad. But consider that this type of thought reform, whereby you can’t ever be sure of the veracity of any claim being made on TV or social media, sets us up for an erosion of democracy.

A recent study on the effect of negative ads on voter turnout in the U.S. found that if no party “went negative” overall, voter turnout went up, but if the Republican candidate went negative, turnout improved solely for them. The reverse was not true for the Democratic candidate. The incentive for conservatives to go negative and win at all costs becomes clear.

Canada can help fix this mess by banning TV and social media ads during elections, meaning any solicitation for votes on behalf of a party or an organization endorsing a party, including unions or political action groups like Ontario Proud. It may sound crazy, but it’s reality elsewhere.

In the United Kingdom, for example, political television ads for elections have always been illegal, and the ban has survived court challenges in the past. Instead of TV ads, parties are allotted time on the BBC for “Party Political Broadcasts,” which are meant to allow candidates to lay out their platforms in a manner they deem fit. There are no guidelines for the format, but the broadcasts are labeled, and widely known, as “Party Political,” so they can’t function as stealth propaganda.

Meanwhile, in October 2019, Twitter announced it will no longer accept political ads on its service, acknowledging that the system can be gamed by the richest or most desperate candidate.

Twitter and Facebook already have different sets of rules depending upon the country they’re operating in. For instance, French and German laws prohibit Nazi propaganda from being displayed, and you’ll find if you change your account’s location to one of these countries, Twitter will show you an error message over the offending material.

While no single country has banned political social media ads, the European Union has been keeping an eye on self-imposed solutions like Twitter’s to see whether they can legislate the use of political ads in member countries, which is an extension of their approach to disinformation and hate speech.

Canada could pass a bill barring Facebook, Instagram and even YouTube from airing political campaign ads, and those companies would be forced to comply or face legal problems.

Instead of using these ads, parties could try to do legwork to build movements, leveraging their followers’ enthusiasm to post on their own social media accounts organically. This is what we saw in 2008 with Barack Obama, and are now seeing with Bernie Sanders.

Alternatively, parties could get out and pound the pavement. Canvassing, going to events and getting out the vote, and just plain visiting voters who never see their representatives, can go a very long way to building support that can sometimes last beyond an election cycle. There is no online or virtual substitute for being with the people and for the people than sharing facetime with constituents and listening.

A ban on political ads could help make these methods more prevalent, and lead to a healthier election climate overall. It is possible, and the time to do it is immediately.