Since Russia invaded Ukraine, Canadian media has been filled with articles and videos promoting local Ukrainian businesses and organizations, including restaurants. One restaurant in Toronto has been particularly popular in the media, being mentioned, recommended and/or profiled in several outlets, including CBC, the Canadian Press, Toronto Star, Toronto Life, BlogTO, and the Toronto Sun. None of these publications, however, mention the fact that the restaurant is decorated with fascist flags and portraits, and sells some of them on their website.

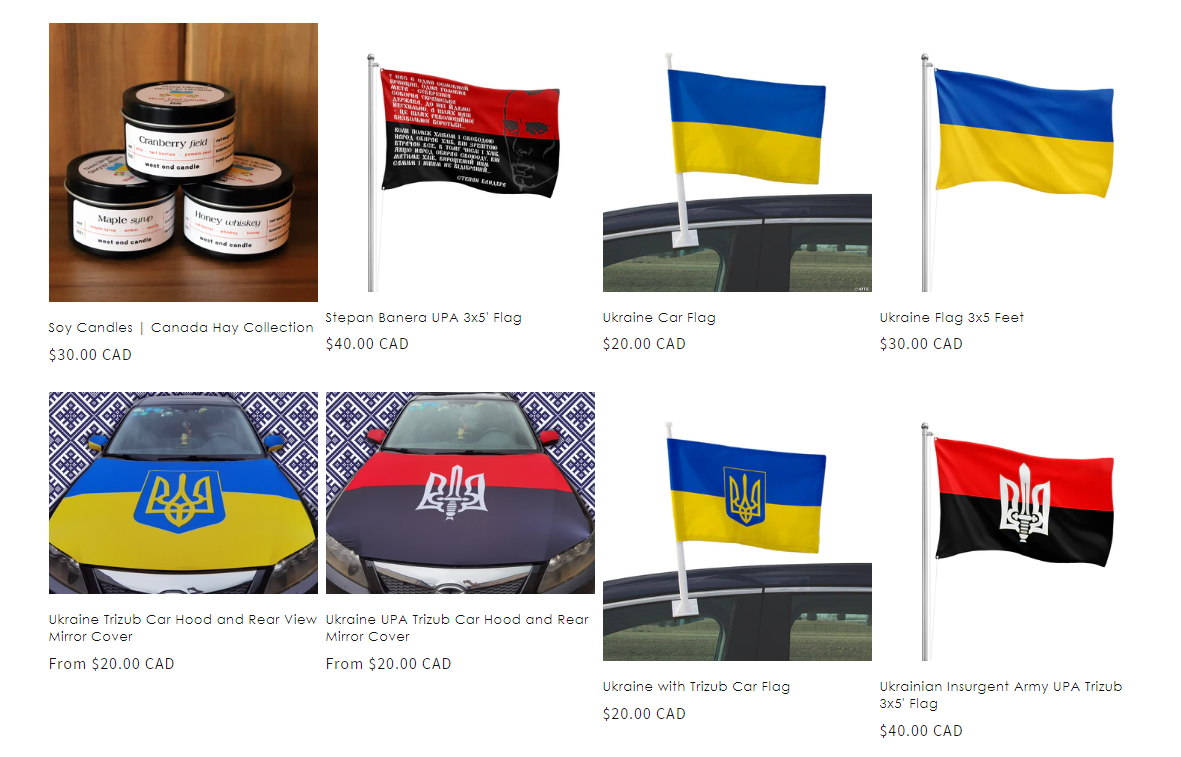

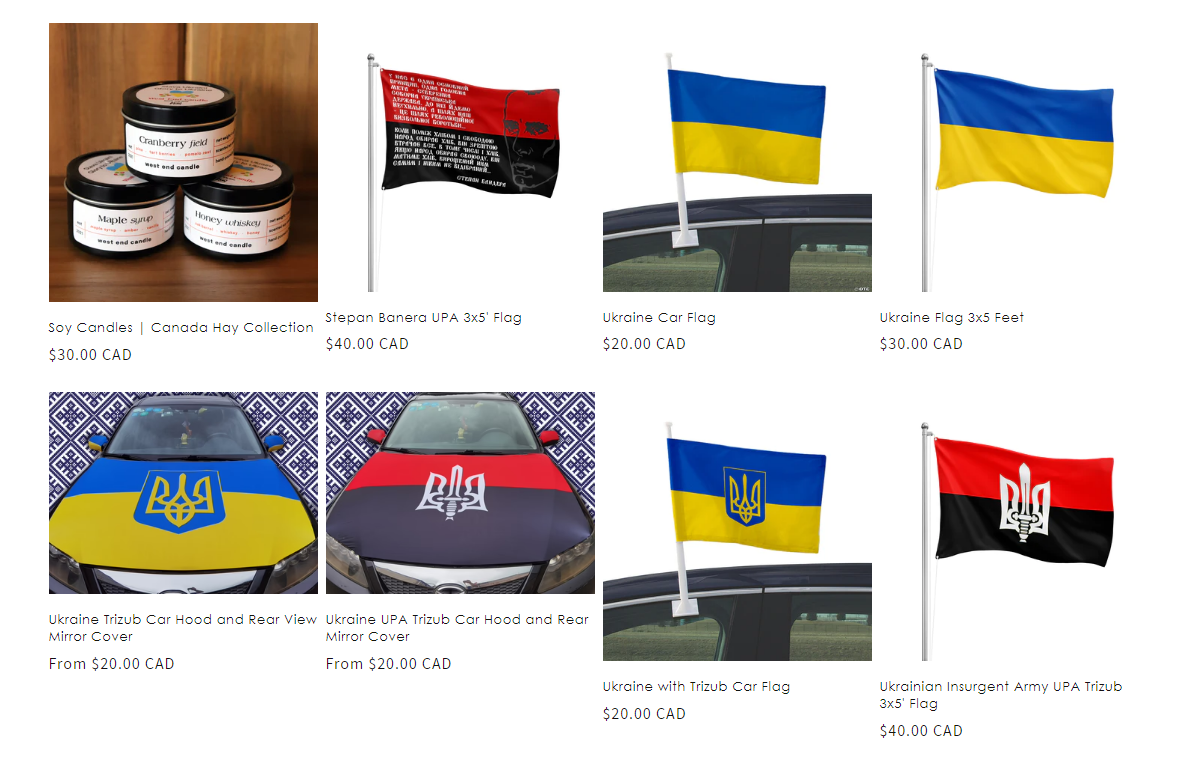

The restaurant’s walls are adorned with the following: several Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) flags, a flag with UPA colours and Stepan Bandera’s face on it, portraits of Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, and an MP40. The restaurant also runs a gift shop, which sells a range of items including a Bandera flag, a UPA flag and car flag, and a UPA car hood cover.

If these names aren’t familiar to you, here’s a quick explainer.

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was a far-right group founded in 1929 that had the goal of establishing an independent Ukraine. The group became increasingly pro-Nazi throughout the 1930s, and eventually collaborated with them. The group split in 1940, and one of the factions became known as the OUN-B, which was led by Bandera.

At Passage, Moss Robeson writes, “The OUN-B hoped to make Bandera the fascist dictator of an independent, ethnically cleansed Ukraine allied to Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler had other plans, but the ‘Banderites’ continued to collaborate with the Germans even after their leader wound up in a concentration camp.” The OUN-B also created the UPA as its military force, which was led by Shukhevych (who had previously been a commander of a Nazi military intelligence formation, the Nachtigall Battalion). To quote from a past article of mine, “In 1943, according to researcher Terry Martin, the UPA ‘adopted a policy of massacring and expelling the Polish population of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.’ Researchers estimate that members of the group killed around 100,000 Polish civilians over the next year.”

The OUN and the UPA also played significant roles in the Holocaust, helping the Nazis exterminate the Jewish population in Ukraine. This is documented in a 2021 book by professor Jean-Paul Himka titled Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust: OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944. A description of the book, published at Columbia University Press, notes: “Triangulating sources from Jewish survivors, Soviet investigations, German documentation, documents produced by OUN itself, and memoirs of OUN activists, it has been possible to establish that: OUN militias were key actors in the anti-Jewish violence of summer 1941; OUN recruited for and infiltrated police formations that provided indispensable manpower for the Germans’ mobile killing units; and in 1943, thousands of these policemen deserted from German service to join the OUN-led nationalist insurgency, during which UPA killed Jews who had managed to survive the major liquidations of 1942.”

The MP40, meanwhile, was a submachine gun invented and used by the Nazis.

The attempted rehabilitation of these groups and figures by Ukrainian nationalists has been condemned by Jewish organizations (both inside and outside Ukraine) and Polish groups, as well as many others.

For example, the director of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee, Eduard Dolinsky, wrote in a 2017 article at The New York Times titled “What Ukraine’s Jews Fear” that, “Government-sponsored institutions are behind the whitewashing. Led by the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, the rewriting of the country’s World War II history is being done to glorify the O.U.N.-U.P.A. while denying the group’s crimes. […] As the historical revisionism has ramped up, so has the desecration of Ukraine’s Holocaust sites and memorials. […] On Jan. 1, a torch-lit march through central Kiev in honor of the O.U.N. leader Stepan Bandera rang out with cries of ‘Jews out.’”

Meanwhile, last year, Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance, an official research institution, tweeted that they were “deeply concerned about Ukraine commemorating the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists ideologue and leader Stepan Bandera: OUN’s armed wing, the UPA, perpetrated the 1943-1944 genocide of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Lesser Poland, which claimed 100,000 lives. In pre-war Poland Bandera organized terrorist attacks, and during #WW2, co-authored the ideology of the OUN modelled on German crimes against Jews.” The glorification of Bandera by some Ukrainians has also caused political spats between the two countries.

On November 24, the restaurant published a since-deleted status on Facebook, noting: “Hi everyone, we are currently being attacked on Twitter for supporting Stephan Bandera, a former OUA leader. As ridiculous as this situation is, we want to emphasize that we ARE NOT NAZIS. We believe Stephan Bandera is a Ukrainian national hero, and his only goal was to make Ukraine an independent state from the Soviet Union. The idea that Bandera is a Nazi collaborator is propaganda to paint Ukraine with a nazi problem. Thank you to everyone who continues to support us. Slava Ukraini.” (This status was posted in response to criticism the restaurant had received, some of which came after I tweeted about it.)

And yet, none of this has been mentioned in media coverage of the restaurant, which instead focuses largely on the donation programs it has set up as well as its supposed role as a spot for the community to gather. The coverage also notes that the restaurant has had a flood of customers since the war began, with patrons who believe spending money there is a way to help out.

The media outlets help bolster this idea, portraying the restaurant as a good representative of the community, and a reputable source on the war. Toronto Life, for example, depicts going to the restaurant as one of “six ways to support Ukraine and a local business, and get a tasty snack while you’re at it.” BlogTO, meanwhile, quotes the restaurant owner as saying, “My advice for anyone that wants to help Ukraine, even if they are not in the financial position to donate money or supplies is to speak up […] Whether that’s in person during the rallies or online, sharing updates and resources. Also, Russian propaganda is widespread and effective. Receiving information from reputable sources is very important to not be conditioned by the pro-Russian narrative.”

The closest we get to any discussion of the restaurant’s decorations is a CBC article published in August. The article features a few photos of the restaurant and its owner, which clearly include the red and black UPA flag as well as the MP40. Despite this, the flags are ignored in the article and its photo captions. A February article at the Toronto Sun notes that “flags drape the walls,” but doesn’t describe any of them. One of the flags is also visible in the back of a BlogTO video shot in the restaurant, but it’s not mentioned by the host.

There are two general possibilities here. First, the journalists may not be aware of what the flags and photos represent, and didn’t bother to ask. Second, the journalists may be aware, but chose to avoid mentioning them. Both are inexcusable.

At this point, journalists should be well-informed on the meaning of symbols such as the UPA flag, or at the very least have editors that are knowledgeable. I argued this back in March when Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland was spotted holding a UPA banner, and shortly after it did seem that some progress was made. Obviously not, though. This is particularly galling in the CBC example, as the flag is completely unavoidable in the photo they chose to include. Moreover, failing to mention the restaurant’s politics would be wrong, in part because apparent support for fascists should always be exposed, and also because these articles talked about the restaurant in a political context already.

This would also be in line with past news coverage of restaurants expressing and/or displaying political views or symbols. For example, after Russia invaded Ukraine, the restaurant Pravda in Toronto became a topic of discussion due to its Soviet theme. Unlike with this restaurant, Pravda made it clear it didn’t endorse these figures or their political views, and yet the media still felt it relevant to report on. Additionally, media frequently reported on restaurants and small businesses that expressed support for the Ottawa Convoy, meaning they don’t hold as a general rule that the politics of businesses aren’t in the public interest.

As a whole, media coverage of this restaurant has been irresponsible. If the media insists on recommending a business that displays symbols of fascist groups it should at the very least make that fact clear to its readers.

The job of the media should be to inform. Instead, in this case they’ve misled the public, sending them somewhere without giving them the facts to make an informed choice, and platforming a restaurant as a reputable voice to readers without describing its political affiliations.