In June, the police services board in London, Ont., passed a motion calling on the federal government to “define femicide in the Criminal Code.” As it stands, there’s no difference in a murder charge if the victim was targeted for being a woman. The argument from the board is that by defining femicide, Canadians can “see it labelled and addressed as a hate motivated crime.”

The Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability (CFOJA) has played a vital role in femicide awareness, publishing information about homicides that involve women, including releasing annual reports documenting numbers of victims. They’ve also been a vocal advocate for the change the London police board is calling for, pointing to similar moves in other countries, and writing, “These are positive steps because it is recognized that those who impose the law must recognize the seriousness of violence before society can effectively respond.”

This all sounds fine, unless you think about it for a little bit. Would making femicide a hate crime change anything? Would making murdering a woman extra illegal decrease rates of femicide in Canadian society? Is amending the Criminal Code the best way to combat violence against women?

For carceral feminism, the answer to these questions is yes: more police resources, better data tracking mandated by the Criminal Code (and not, say, by a statistics agency), and more awareness, are what’s necessary to address this crisis. Carceral feminism sees the prison system as one solution to fighting violence against women. If perpetrators are properly criminalized, they argue, there will be both deterrents and punishments for the men who murder women.

One problem with this logic is that in 2021, 24 per cent of men accused of intimate partner femicide in Canada killed themselves after, meaning deterrence wouldn’t have made a difference for them. But the broader problem is that carceral feminism simply perpetuates the criminal (in)justice system.

Intimate partner violence is complex and usually escalates from more minor incidents before it results in murder. The presence or absence of social factors such as poverty or financial dependence on a partner, housing, access to schools and childcare, the ability to drive and access to the shelter system as well as a supportive family or friend network can all make leaving a relationship difficult. If someone does manage to leave, the paltry support services available to them often means that they’re still not away from danger. The root causes of these problems aren’t going to be solved through changing the Criminal Code.

Further criminalizing femicide would, however, probably result in giving police more resources. This is why it’s not surprising that this call is also coming from a police services board. But the police have demonstrated that they’re not the right body to manage violence against women in the first place, which is reflected in the fact that a 2018 survey of survivors of intimate partner violence in Canada found that just 35 per cent reported it to them.

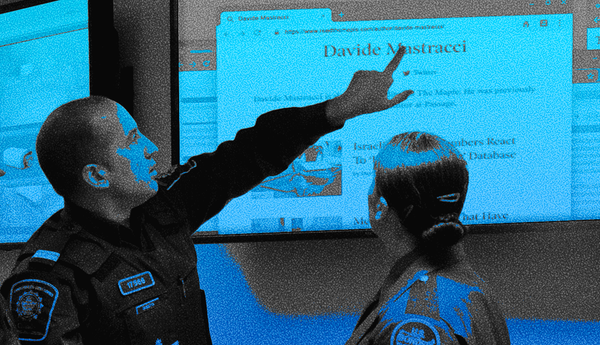

In 2017, The Globe and Mail published an investigation by journalist Robyn Doolittle into how seriously police forces across Canada take sexual violence. She found that the London Police Service had an especially high number of “unfounded” cases (i.e., cases where police determined that charges aren’t warranted). In 2020, the citizen-led coalition in London who worked to help re-examine unfounded cases reported that they only got through fewer than 20 per cent of cases in the past year. Are we supposed to believe that one of the barriers to the police taking violence against women seriously is that it isn’t considered a hate crime?

Hate crime language is also hardly the panacea that some might hope. Consider the case of the man behind the 2017 Quebec City mosque massacre. He was ultimately charged with first degree murder — not a hate crime or terrorism — for the murder of six men inside the mosque. The man was obviously motivated by hate, but the Crown’s logic was that seeking hate crime or terrorism charges was a riskier strategy than striving for first-degree murder, as a judge might not agree with the burden of proof necessary to achieve a successful conviction. By charging the man with first-degree murder, the Crown would have a straightforward path to a conviction. That’s what he was charged with and ultimately pleaded guilty to.

In 2021, 173 women and girls were murdered in Canada, according to the CFOJA. About 5 per cent of them were murdered by a stranger, while about 35 per cent were murdered by a current or former intimate partner. In cases where the victim’s identity was known, about 51 per cent were racialized and/or Indigenous women. This reality clashes with the idea that justice for these women can be achieved through the system as it stands.

In a 2021 report prepared for Women’s Shelters Canada, authors Amanda Dale, Krys Maki and Rotbah Nitia write, “For the small percentage of survivors who go to the police, reporting is a painful retelling of trauma even if it is in the presence of an advocate. Victims who make a police report may also experience secondary victimization that can be more harmful than the victimization itself. Despite the predominance of carceral justice, many survivors want their offenders to be rehabilitated rather than incarcerated. People of colour are disproportionately charged, convicted, and imprisoned. Incarceration doesn’t always or often address survivors’ other needs for healing, or the structural root causes of [Violence Against Women/Gender-Based Violence].”

Rather than achieving what proponents hope for, the struggle to have femicide written into the Criminal Code is, at best, a distraction, and at worst, a move that will bolster systems already over-incarcerating, over-policing and under-serving racialized and Indigenous communities.