Although both the Liberals and Conservatives enjoyed their highest vote shares in decades in last month’s federal election, experts say both parties have areas of support that are soft and could shift back to smaller parties in the years ahead.

Ninety-one per cent of MPs in the House of Commons are now Liberals or Conservatives, a nine per cent increase from the results in 2021. The two parties won a combined total of 85 per cent of the popular vote, a nearly 20 per cent increase from the previous election and the first time both parties scored more than 40 per cent each since 1930.

The Liberals won the highest vote share of any single party since the 1984 federal election, while the Conservatives saw their own highest score since the party was formed in 2003.

But experts interviewed by The Maple note both the major parties — particularly the Liberals — drew support from strategic voters who were primarily focused on keeping out their least preferred option rather than supporting a party that they were genuinely enthusiastic about.

That means the high levels of support both the Liberal and Conservative parties received could fluctuate over the coming months and years — and it means smaller parties, like the NDP, which took a pummelling on election night, are likely to re-emerge.

“We have seen parties go through near death experiences before,” said Stewart Prest, a political scientist at the University of British Columbia. “So the NDP can return from this.”

Many voters who were concerned about U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade tariffs and repeated threats of annexation following his inauguration in January likely felt pressure to vote Liberal — far more so than they would have done just a few months prior, said Prest.

On the other hand, for voters who were more focused on decisively breaking with the legacy of the Trudeau government — including some past NDP supporters — the choice was more likely to be Conservative.

Polling by Abacus Data showed that 45 per cent of voters said the cost of living was their top priority in the election, while 30 per cent said dealing with Trump was their main concern.

These circumstances left much less space for “alternate parties,” Prest said, and the NDP’s resulting collapse fed support to both the Liberals and Conservatives. The now-leaderless NDP was reduced to seven seats and will lose its official party status in the House of Commons.

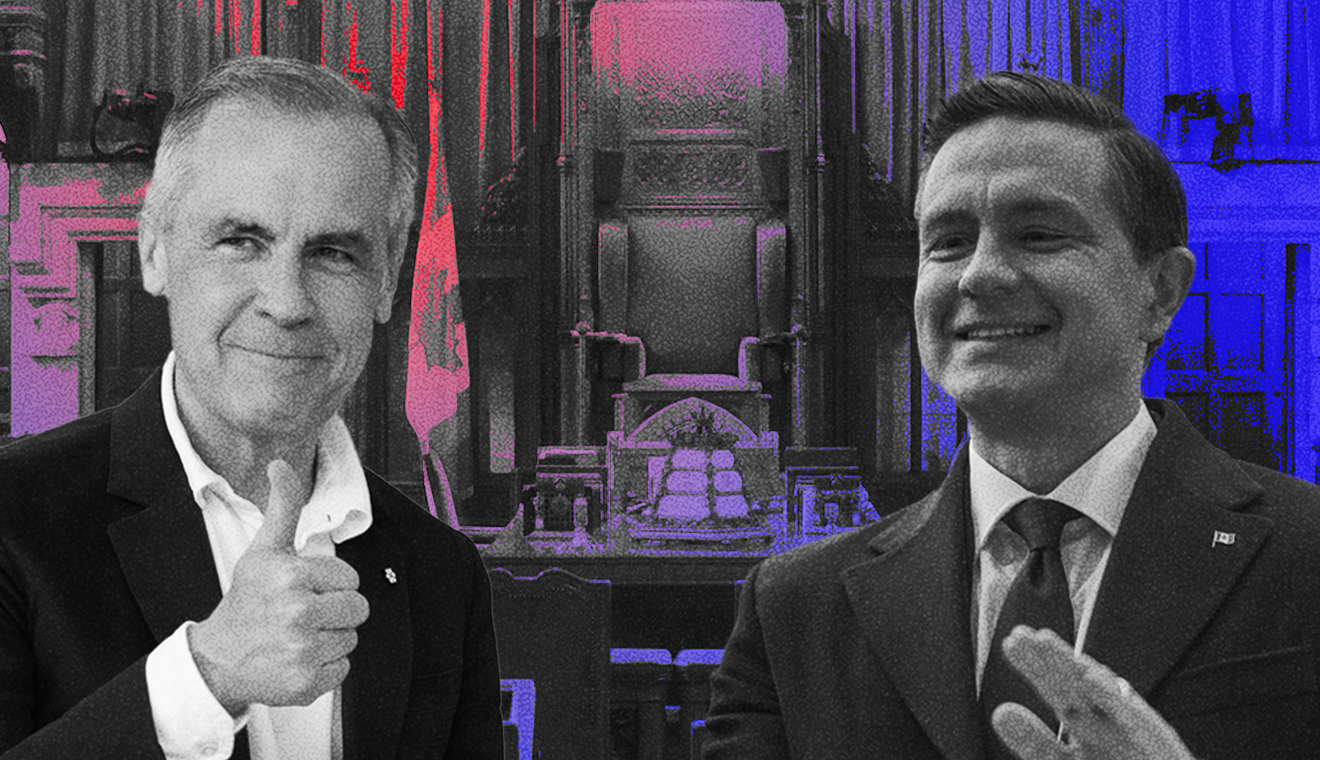

Despite the gains made by the two largest parties, said Prest, neither is likely to be happy with the outcome of the election. The Conservatives blew a more than 20 point lead they held at the start of the year, and their leader, Pierre Poilievre, lost his own seat in Carleton. The Liberals, yet again, failed to win a majority despite being projected to do so during much of the campaign.

Many of those who voted Liberal were likely not keen to do so, but felt it was necessary to keep Trump’s politics — and his threats — out of Canada. It’s unlikely that the Liberals would have won the election were it not for that dominating issue, said Prest, begging the question of what might be in store ahead for the party.

But the Conservatives have to reckon with the relatively soft and strategic basis of some of their support too.

Prest said some of the party’s supporters in this election — particularly younger voters — who helped tip it above 40 per cent of the popular vote for the first time in the modern party’s history are unlikely to be particularly enamoured with Conservative politics or ideology per se.

But many of those voters were frustrated with the current direction of the country amid the cost of living crisis, and simply wanted to see a change.

The party also has its own internal divisions. On the one hand, a large chunk of the party’s base is highly supportive of Trump and Poilievre’s right-wing populist message. Forty five per cent of Canadian Conservatives wanted Trump to win the U.S. presidential election last fall, according to a Leger poll.

But others, including some members of the party who have spoken critically of Poilievre’s failure to win the election, are eager to shake off that association with Trump, who they see as electorally toxic in Canada.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s campaign manager, Kory Teneycke, for example, accused Poilievre’s team of “campaign malpractice” for blowing the Conservative Party’s lead and refusing to focus on concerns about Trump.

On some issues, such as abolishing the carbon tax, Poilievre was adept at bringing mainstream voters over to a populist position. But that was much harder to pull off when Trump began openly threatening to make Canada the “51st state,” said Prest.

“Poilievre was quite slow to turn to really confront the issue of Donald Trump, because he really didn’t want to, because that was, in a sense, alienating to his core positioning,” which, Prest added, emulates Trump’s tendency to denigrate political opponents as not just wrong, but illegitimate.

“Conservatives don’t seem to be able to move away from that [populist] group, and the rest of the country is unwilling to move towards that group.”

Where Now For Smaller Parties?

Historical precedent and the fact that Canada has had a multi-party democracy for decades are other reasons why it is premature to declare that Canada is now locked into a two-party system, said Laura Stephenson, a political science professor at Western University who specializes in political behaviour.

“There are likely a lot of people who still really support the NDP or the Bloc or the Greens or whoever they might have voted for in the past who just this time around decided to make a different choice,” Stephenson told The Maple.

Nonetheless, Stephenson said over the past two decades Canadian politics have seen a polarization between a right-wing side — especially since Stephen Harper united Canada’s conservatives under a single banner in 2003 — and a broadly perceived “progressive” side that she said became more defined after Justin Trudeau became prime minister in 2015.

Under Mark Carney, however, the Liberal Party tacked rightward to its traditionally more “centrist” position. The current prime minister talks of fiscal restraint and making Canada into an oil and gas “superpower.”

Should this have opened up political space for the NDP to fill?

Prest noted that one of the problems the NDP faced in this election is common to junior partners in governing coalitions or, as the case was for the NDP between 2022 and 2024, confidence and supply agreements.

Voters, he said, tend to punish the smaller party in such arrangements around the world.

The NDP’s agreement with the Trudeau Liberals introduced dental care, but overwhelmingly reaffirmed or extended the Trudeau government’s existing promises, leading some commentators to question whether the NDP still had any meaningful reason for existence.

But regardless of the NDP’s ability or not to distinguish itself from the Liberals, all of the experts interviewed by The Maple agreed that one of the main driving factors in this election was the question of who was best suited between Carney and Poilievre to deal with Trump.

Adam D.K. King, a labour studies professor at the University of Manitoba and the author of The Maple’s Class Struggle newsletter, said the U.S. trade war and a desire for stability under Carney was the main story behind the NDP’s collapse on election night.

“Certainly the party has its failures, and one of them is a failure to differentiate itself from the Liberals,” he said. “But I don’t think that this election result is really the kind of existential crisis for the party that some people think it is.”

He noted that minority parliaments open up strategic opportunities for smaller parties like the NDP to extract concessions from the Liberals.

“The trade off of that, of course, is always that come election time, it was going to be very difficult to remind voters that you were, in fact, the ones who got dental care or anti-scab [legislation],” said King.

If Canada was to do away with its current first-past-the-post voting system — as Trudeau infamously promised he would during the 2015 election before reneging on that pledge — and replaced it with a proportional representation system, smaller parties like the NDP would be more likely to run certain ministries in minority governments, said King.

In that scenario, it would be much easier for the party to remind voters of its achievements in power come election time.

Amid the collapse of the smaller parties at the ballot box, last month’s election results have renewed long-standing calls for electoral reform in Canada.

Ted Cragg, an organizer with Fair Vote Canada, which advocates for electoral reform, told The Maple that the circumstances of this election forced voters into a corner, and many voted strategically for parties that they didn’t particularly like.

But even then, the number of seats won by each party didn’t accurately reflect who the public actually voted for. As noted above, the Liberals and Conservatives combined won 91 per cent of seats in the House of Commons with 85 per cent of the vote.

But in some regions, the results were even more skewed. The Liberals won just two seats in heavily Conservative Alberta, or about five per cent of the total number of seats up for grabs. However, the Liberals actually won a much more significant chunk of the popular vote in the province, 28 per cent.

“The results are always skewed under first-past-the-post,” said Cragg. “We never really get what we voted for. Either one party gets too many seats or another party gets too little.”

He said there is a danger in the times ahead that urgent issues continue to pressure the public into strategic voting at future elections, thereby taking Canada down a path towards a more entrenched two-party system similar to what is seen in the United States.

“You can imagine after 10 years or so, that we’re basically reduced to a two-party system,” said Cragg. “Is that really what people want? Because it’s certainly a possibility.”

“If you have proportional representation, it gives voters those choices. You get parties that reflect those choices, and it forces politicians to work together.”

Fair Vote Canada is pushing everyone from party leaders, strategists, candidates and former elected officials to put electoral reform back on the agenda under the new Liberal minority government.

“You need to have as much partisan support and buy in as possible. It’s kind of that cross-partisan lobbying that we work on,” he explained.

Deeper Issues For The NDP

But aside from the problems of Canada’s voting system and the pitfalls of strategic voting, a deeper issue for the NDP, said King, is the phenomenon of “class dealignment,” whereby some working-class voters who in the past would be more likely to vote for left-leaning political parties lend their support to Conservatives instead.

In last month’s election, some seats in the industrial heartland of Ontario’s Hamilton-Windsor corridor — an area at the forefront of Trump’s trade war — flipped to the Conservatives.

“This is related to the larger question of the appeal of right-wing populism to non-college educated working people,” said King.

“To the extent that the NDP was the traditional party of working-class people, particularly in the industrial working-class, the party has shifted away and is increasingly, like social democratic parties the world over, becoming the party of college-educated progressive professionals.”

Reconciling those two groups in a viable electoral coalition is becoming increasingly difficult, said King. The challenge for the NDP, he explained, is to get voters to think of themselves as working-class in a reality where the composition of the working-class itself is much more differentiated than it has been in decades past.

King said that while some may be breathing a sigh of relief that Poilievre was kept out of power, Canada is headed for dangerous times under Carney.

“If you really actually look at what he is proposing, there’s no way around it. There are some, if not straight up cuts, then they are at least sort of preventing growth in a way that kind of amounts to a real cut,” said King.

“I think we’re in for a bit of a dark period here.”

King said — and has argued in his Class Struggle newsletter — that activists on the left need to organize themselves for the “long haul.” An irony of the NDP losing its official party status in Parliament, he added, is that it opens up more opportunities for involvement in the party at the local level.

“When the party loses official party status, the money goes away, and so the party actually becomes more dependent on its members, so local riding associations are going to have to tap their members for funds and to increase their membership base,” he explained.

“That, in and of itself, may encourage some people to get more involved in organizing the party. So there are strategic opportunities.”