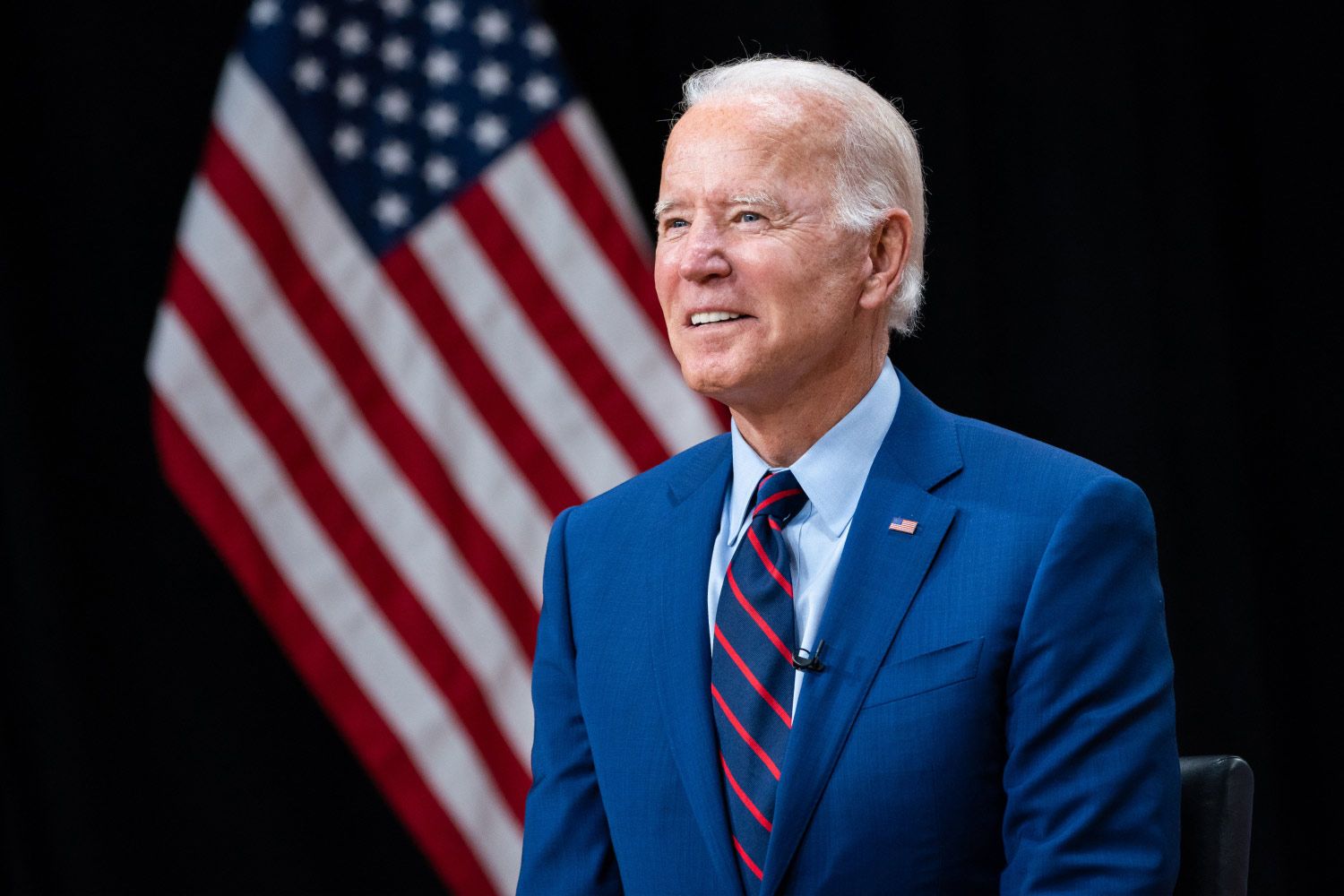

Earlier this month, the White House Task Force on Worker Organizing and Empowerment released its final report to United States President Joe Biden. The report offers proposals for how to strengthen the American labour movement, an objective that it says “is critical to growing the middle class, building an economy that puts workers first, and strengthening our democracy.” The task force is chaired and vice chaired by Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh, respectively.

In his executive order establishing the task force, Biden instructed that, “The Task Force and its members shall identify executive branch policies, practices, and programs that could be used, consistent with applicable law, to promote my Administration’s policy of support for worker power, worker organizing, and collective bargaining.” In its stated objectives, the task force was ostensibly meant to partially make good on Biden’s promise to be “the most pro-union president” in U.S. history.

As a presidential candidate, Biden made several commitments to unions that have yet to materialize. Unions played a critical role in electing Biden, particularly in the midwest rust belt states, where the proverbial “blue wall” was resurrected after Donald Trump was able to peel portions of these voters away in 2016. Indeed, in the November 2020 election, Biden won 57 per cent of union households, compared to Trump’s 40 per cent (a figure that is still, admittedly, embarrassingly high).

The Task Force’s report comes at a moment of historic union weakness in the U.S. Despite the hopes of many last year that “striketober” would mark a seachange in the trajectory of American labour, the latest figures confirm a decades-long story of union atrophy and decline.

Union density in the U.S. hovers at 10.3 per cent nationally, the same as it was in 2019. Unions lost roughly 241,000 members between 2020 and 2021. Public sector union density is now 33.9 per cent, a good deal better than the private sector but quite paltry compared to public sector unionization in Canada, which, at roughly 77 per cent, is basically at saturation. In 1983, the first year comparable U.S. data were collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 20.1 per cent of workers were union members. Some see promise in young workers flocking to the labour movement, yet unionization among workers between the ages of 25 to 34 is only 9.4 per cent, lower than total density.

High-profile strikes, such as those at John Deere and Kellogg’s, enthused labour commentators, but they didn’t have much of an impact on the “work stoppages” data for 2021. Last year, there were only approximately 80,700 workers involved in 16 major work stoppages, which the BLS defines as a strike or lockout involving 1,000 workers or more and lasting at least one shift. Although this is up from the eight stoppages recorded in 2020, it simply brings the number back to the yearly average of the past 20 years. For historical comparison, there were 470 work stoppages involving at least 1,000 workers in 1952, when the workforce was much smaller.

Moreover, 2021 saw only half as many strikes as 2018 and 2019 when large, state-wide teachers’ strikes and strikes at General Motors, respectively, made headlines. What the BLS refers to as “days of idleness,” which measures the percentage of working hours lost to work stoppages, clocked in at 0.002 per cent and was barely noticeable in 2021.

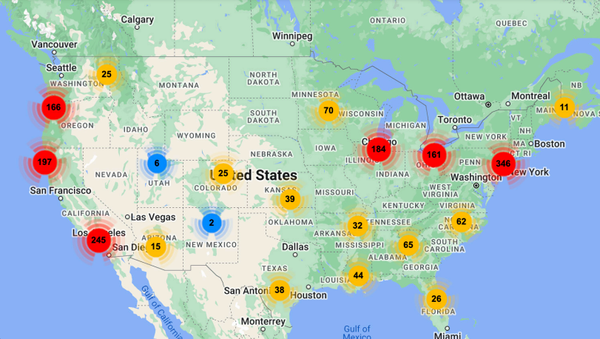

Of course, the BLS only counts work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers, but including data for all other American strikes doesn’t make much of a difference. The Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) previously collected this data, but as Doug Henwood showed in 2018, it mostly tracked the larger workplace trends reported by the BLS. Trump instructed the FMCS to stop collecting these figures and Biden has yet to undo his predecessor’s directive. However, the IRL Labor Action Tracker at Cornell University collects data on all strikes and lockouts in the U.S. They counted just 370 work stoppages in 2021, which is a far cry from the 1,142 strikes with fewer than 1,000 workers recorded by FMCS in 1985.

No matter how you slice it, the American labour movement is in rough shape, and rampant income inequality is one telling consequence.

However, unlike in Canada where labour and employment are mostly provincial matters, there are some things that can be done federally to change the landscape of union organizing and worker power in the U.S. The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act was the great hope of many. Among other things, it would have made it easier to unionize by greatly restricting employers’ ability to thwart union drives, cracking down on employee misclassification and ending right-to-work laws, which allow bargaining unit members to opt out of paying dues. However, despite the Biden administration’s support for the bill and its passage in the House of Representatives, the PRO Act cannot pass in the Senate due to the filibuster rule requiring 60 of 100 votes (which means about 10 Republican votes, presently). With comprehensive labour law reform stalled in the Senate — and the Biden administration unwilling to abolish the filibuster — all that remains are executive orders and tweaks to existing laws.

Although Biden’s National Labor Relations Board appointments have been promising, he so far hasn’t exercised strong executive authority when it comes to labour issues. Most of Biden’s executive orders pertaining to labour have been directed at repealing Trump policies. As this demonstrates, executive orders can always be undone by future presidents, but governing according to what might happen when you next lose an election hardly inspires enthusiasm or confidence among your voting base.

The task force report ostensibly seeks to correct for Biden’s seeming reluctance thus far and makes nearly 70 recommendations for ways to use executive power to strengthen unions and promote collective bargaining. Its suggestions fall into three broad categories: having the federal government act as a model act in its own labour relations; making workers more aware of their existing rights; using federal procurement policy to encourage unionization among government contractors.

Positioning the federal government as a model labour regulator largely involves removing barriers so that federal employees across agencies can more easily unionize and collectively bargain. The U.S. federal government, with 2.1 million employees, is the largest employer in the country. However, only about 1.2 million federal government workers are covered by collective agreements, and fewer than 20 per cent of federal workers are union members. Worse still, since the AFSCME v. Janus Supreme Court decision in 2018 instituted right-to-work in the federal public sector, only about 33 per cent of employees currently covered by a collective agreement pay union dues. That’s around 835,000 federal employees enjoying the benefits of union contracts without paying dues, thanks to the right-wing attack on union security.

The task force recommends a suite of policies to empower federal government workers across agencies to join unions and collectively bargain. Mostly, this involves encouraging union membership in federal agencies and instructing departments to undertake reviews to ensure no federal employees are misclassified as being ineligible for union membership. However, with Janus in force, one wonders how much right-to-work would blunt the impact of many of these provisions.

The report suggests that the federal government should do more to provide workers with information about organizing, and ensure that the process of certifying a union is transparent and timely. This includes using agencies like the Labor Department to ensure workers have greater knowledge about their labour rights. There are, however, significant limitations when it comes to recommendations of this sort. Low union density is not in any meaningful sense the result of a lack of awareness on the part of workers. Rather, it’s the outcome of laws that allow employers to quash union organizing with few consequences, if any. The task force does recognize employer intimidation and reprisals as serious problems and makes recommendations for how to curb this behaviour, yet without labour law reform these would amount to very little.

Along the same lines, the report calls for improvements in the efficiency of the National Labor Relations Board and the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, particularly to ensure newly certified unions are able to bargain their first collective agreements. More than half of new bargaining units aren’t able to bargain a first contract within a year of certifying, largely due to employer resistance and chicanery. There is very little that American unions can do about this through legal challenges. Without robust labour law reform through Congress, the executive branch can make minor regulatory changes to improve the operational functioning of federal agencies, but much more will be needed to rein in the power of bosses to resist first contract bargaining. As in many instances, because the president can’t expressly implement new policies, the most the task force can do is promote better adherence to and enforcement of existing laws and regulations.

Last, the task force makes a great deal of the federal government’s ability to leverage its purchasing and procurement power to favour unionized firms or to at least cease contracting with businesses that engage in labour violations. As the report recognizes, unionized firms are frequently undercut by lower-wage, non-union firms in the federal bidding and contracting process. Only by prioritizing contracting with unionized firms can this be reversed. The report insists the federal government can promote unionization and collective bargaining through its contracting with private firms and through the various grants and funds it distributes and administers. However, it’s also important to recognize that the government has many of these contracting relationships because of decades of privatization and outsourcing. Many former government and public services were handed over to the private sector as part of the overall neoliberal austerity program. Now, the Biden Administration finds itself trying to use government purchasing power to encourage unionization among government contractors.

The power and influence of American labour has been on a long decline since the mid-1950s. Yet, union density isn’t low in the U.S. today because unions are unpopular. As the report points out, the latest polling suggests around 68 per cent of Americans approve of unions, which is the highest approval rating since 1965. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, there are roughly 207.2 million working-age adults in the U.S. With union density sitting at 10.3 per cent, that means there are just under 185.9 million non-union American workers. If polling is correct and 52 per cent of them want to be union members, that’s around 97 million workers who would swell the ranks of organized labour, if given the opportunity. Add them together with the 14 million current union members and the U.S. would have union density just shy of 60 per cent. In other words, if workers’ preferences actually had any impact on policy, the U.S. would have Norwegian or German levels of union coverage instead of being the bosses’ paradise that it presently is.

There’s nothing in the task force’s recommendations that could achieve the above level of union membership. Even if by some miracle the PRO Act passed the Senate, bringing substantial numbers of American workers into the labour movement would likely be a decades-long process. The American labour movement therefore needs to get creative about ways to reach and organize new members. Biden’s worker organizing task force, unfortunately, is mostly tinkering around the edges.

Member discussion