Here we are, once again. Another lawful strike has been crushed, after the Alberta government fast-tracked back-to-work legislation to end a province-wide teacher walkout that began on October 6.

On October 28, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith’s United Conservative Party (UCP) government passed Bill 2, the Back to School Act, ending job action by more than 51,000 members of the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). Rather than bargain with teachers and address longstanding issues of stagnant pay and overcrowded classrooms, Smith and the UCP chose for the legislative hammer.

The Bill quickly received royal assent that day, sending teachers back into under-resourced classes by mid-week under an imposed collective agreement retroactive to 2024. Continuing an “illegal strike” would carry penalties of up to $500 per day for individual members and up to $500,000 for the union, according to the text of the bill.

Knowing that this intervention was wholly unjustifiable, the UCP invoked the “notwithstanding clause” to shield its strike-breaking bill from a court challenge. This rarely used section of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms allows governments to override constitutional rights in limited situations. It’s the first time a government in Alberta has used the controversial clause.

This is a dark moment in Canadian labour history.

Perhaps the most right-wing government in Canada has trampled on workers’ Charter-protected right to strike and taken the dangerous step of insulating its actions from legal scrutiny. What’s more, the UCP government’s intervention may further encourage other Canadian governments to run roughshod over collective bargaining rights, particularly in the public sector. Last week’s events are yet another example of the increasingly authoritarian attacks on organized labour.

Through a union press release, ATA president Jason Schilling indicated the union would abide by the back-to-work order, while continuing the fight through other, unspecified channels: “Teachers will comply with the law, but make no mistake—compliance is not consent. The Association will fight this abuse of power with every tool the law provides and every ounce of conviction we possess.”

As the union further specified, however, compliance with the law will include teachers refraining from all job actions short of a full labour withdrawal, including work-to-rule tactics such as refusing to engage in extra-curricular activities. It’s back to business-as-usual across Alberta school boards, in other words.

Not all was calm in Alberta, however. Students from 45 schools across the province participated in walkouts and sit-ins to support their teachers. For example, at Bellerose Composite High School and St. Albert Catholic High School, students staged walkouts in protest, while hundreds of others in Edmonton joined similar actions.

The union has since announced plans to challenge Bill 2 legally, though how this will be done remains unclear. By invoking the “notwithstanding clause,” the Alberta government has pre-empted a Charter challenge, while effectively admitting that its actions are unconstitutional. Options for legal contestation therefore appear limited, if not entirely foreclosed.

From the beginning, this has been a highly contentious round of bargaining. The ATA and the Teachers’ Employer Bargaining Association had been negotiating since early 2024, with Smith and her government, who ultimately control the public purse, refusing to address teachers’ demands for improved pay and smaller class sizes.

Although Alberta educators earn slightly more than the national average for their profession, teacher salaries have increased by only 5.75 per cent over the past decade, according to their union. The rising cost of living has therefore steadily eroded any advantage teachers in Alberta once enjoyed.

Burgeoning workloads are aggravating this decline in real wages. Alberta stands apart as one of only two provinces in Canada without collectively bargained student-to-teacher ratios.

According to the Teaching and Learning International Survey — a worldwide study of teachers’ working conditions conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development — Alberta teachers experience the highest levels of occupational stress in the more than 50 surveyed countries. Forty-two per cent of teachers in Alberta reported experiencing high stress levels, compared to 19 per cent of teachers globally. Only 13 per cent felt respected by their government, a finding that would now likely be even lower.

Instead of addressing these issues, the Alberta government will now impose a contract that teachers have already twice rejected. A 12 per cent wage increase over four years and a promise to hire 3,000 additional teachers won’t undo years of lagging salaries nor guarantee manageable classroom sizes.

The lack of a militant response from the Alberta teachers’ union and the broader provincial labour movement makes this episode all the more depressing. While provincial and national labour leaders convened to publicly condemn the government’s action, no concerted pushback was forthcoming. Talk of a “potential general strike” has translated into little else for the time being.

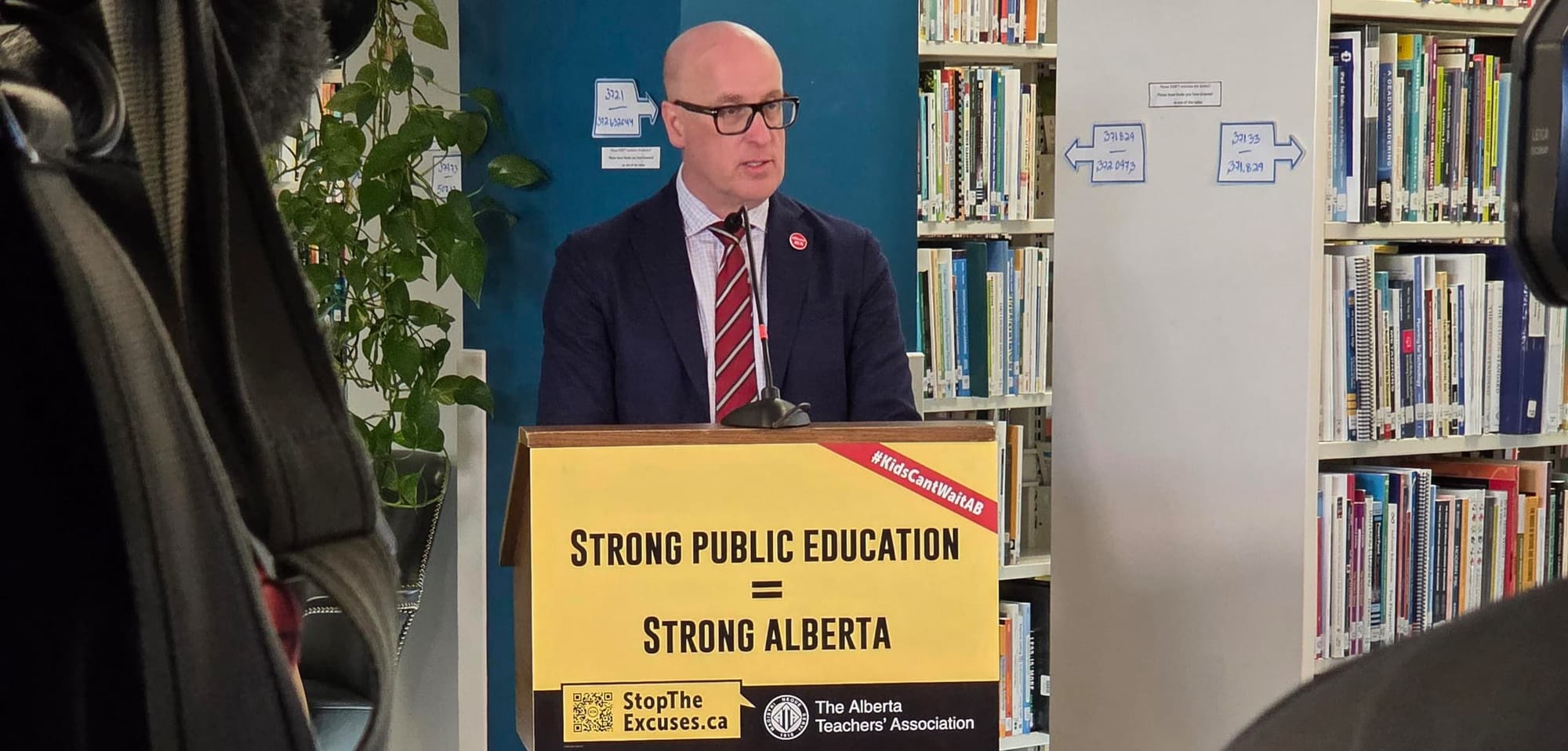

At this press conference of union leaders, Alberta Federation of Labour (AFL) president Gil McGowan indicated that co-ordinated strike action could be forthcoming if other options fail.

“We will begin the process of organizing towards a potential general strike in Alberta,” McGowan told supporters and media at the Ironworkers Hall in Edmonton. Alberta’s finance minister, Nate Horner, dismissively said this sounded like “a plan to make a plan,” suggesting the government isn’t exactly quaking in its boots.

Labour leadership is still gauging interest in a general strike. Yet with teachers and students back in class, the window to mount a fightback is quickly closing. In the long-term, McGowan suggested that labour would instead work toward toppling the UCP government through recall elections. This is not exactly the call to action that mobilizes thousands while the attack is extant.

Leading up to the teachers’ strike, the Alberta labour movement seemed to be building the organizational infrastructure to take on a fight like this.

While 26 unions representing more than 170,000 workers belong to the AFL, a recently formed “Common Front” of unions brings together many more unions, some of whom have a history of militancy. Unions in the Common Front signed onto a “solidarity pact,” committing to take “decisive action” together if any one member organization is attacked by a government or employer.

If there was ever a moment that calls for “decisive action” this is certainly it.

When Ontario Premier Doug Ford attempted to ram through strike-breaking legislation and impose a contract on education workers, the response from the Ontario School Board Council of Unions was immediate and decisive. Defying Ford’s back-to-work order — as well as the government’s use of the notwithstanding clause — education workers, led by current Ontario Federation of Labour president Laura Walton, forced the Conservatives to back down, repeal the legislation, and negotiate with the union. The entire labour movement rallied and credibly threatened a general strike across Ontario.

Similarly, when the federal government invoked s. 107 of the Canada Labour Code yet again to crush flight attendants’ strike against Air Canada, workers and their union refused to stand down and strong-armed the employer back to the bargaining table.

Although the contracts secured out of these episodes are not without criticism, the defiance of workers demonstrated that resistance to unjust government actions is not only possible but absolutely necessary.

The postwar ‘compromise’ between workers and unions on one side, and employers and governments on the other, is on life support. More than a few governments have clearly decided they are no longer willing to be constrained by the legal trappings of Canada’s collective bargaining regime: they’ve unilaterally opted out. Despite the constitutionalization of collective bargaining and the right to strike, governments are willing to break the law now and worry about the consequences later, if at all.

The question before the labour movement then is this: How much longer are we willing to comply with a legal regime wherein governments treat our rights as optional?

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- October 27 | CIRB Rules Against Canada Post Union’s Back-To-Work Challenge

- October 20 | Capitalism And Colonialism: How Modern Canada Was Made

- October 13 | Charges For Workers’ Rights Violations Drop 90% In Ontario

- October 6 | The Minimum Wage Increase In 5 Provinces Isn’t Enough