Canada is facing a housing affordability crisis. There is perhaps no issue on which greater numbers of people agree.

More than one in five people are living in an unaffordable home. Rents have become completely “untethered” from wages, making housing costs unmanageable for low-waged workers in every province. Millions of houses are either damaged, over-crowded or too expensive for people to live in them. People often wait years for affordable housing. The number of homeless encampments has grown rapidly across the country. In Ontario, municipalities counted at least 1,400 encampments in 2023.

To say the situation is dire would be an understatement. Who to blame and what to do about it generates less agreement, however.

Rather than direct the focus where it belongs — on the real estate sector, landlords, private developers and the governments who serve them — politicians and policymakers have taken to scapegoating new immigrants for Canada’s lack of affordable housing. This is both dishonest and dangerous. While Canada’s population has surged recently, immigrants are not to blame for skyrocketing housing prices and rents. Rather, our housing crisis has been decades in the making.

For years, governments have abandoned any serious commitment to building and financing public and other affordable housing. In the 1990s, the federal government dumped its housing responsibilities onto the provinces, who in turn further devolved them to cash-strapped municipalities.

In keeping with their general program of public austerity, the Liberal governments of Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin divested the federal government of its public housing stock and cut funding for new construction. In the years since, lower levels of government, lacking revenue raising capacities comparable to the federal government, have not adequately built or maintained social housing.

According to some experts, Canada would now have to double our number of social housing units to even reach the average among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development peer nations.

Beyond public housing, governments have also neglected to use the tools necessary to ensure sufficient numbers of “purpose-built” apartment buildings with affordable units are built. Instead, with government encouragement and subsidies, developers have built an oversupply of unaffordable condos in urban centres, offering a place for investors to park cash, but leaving families struggling to find suitable accommodations and pushing greater numbers of working class people out of major cities.

Yet despite public pronouncements and budget commitments ostensibly meant to address it, the housing crisis has only grown more dire. Higher interest rates following the post-pandemic inflation in particular put additional pressure on housing costs, exacerbating a more generalized affordability crisis. While much attention was understandably focused on homeowners whose mortgage payments shot up, higher borrowing costs were also bad news for tenants.

As Ricardo Tranjan, a researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, argues, many landlords passed the costs of higher interest charges on to tenants in the form of rent increases, particularly those landlords whose buildings were exempt from rent control laws. Moreover, units that turned over saw rent increases as much as 40 per cent in 2023. Yet as the Bank of Canada begins lowering its policy rate and homeowners breathe a sigh of relief, many tenants will continue to pay inflated prices.

Even when interest rates were lower, between 2009 and 2018, tenants in many cities saw cumulative rent increases well above inflation. Tranjan notes that over this period rents went up by 35 per cent, while inflation grew by 17 per cent.

To the degree that they have addressed housing issues at all in past years, governments have largely tinkered around the edges, with the ultimate objective of increasing homeownership through greater access to credit. The contradiction here is that these policies, while facilitating mortgage access and home ownership, also contribute to housing price inflation by increasing demand and deepening housing financialization. The Liberal government’s various saving plans and tax incentives are a prime example of this approach.

Despite beginning to publicly acknowledge the extent of our housing problems, the federal government has remained steadfast in its commitment to home ownership and the promotion of market-based solutions. While it passed legislation recognizing housing as a human right in 2019, and has since increased funding for various forms of affordable housing, these gestures have paled in comparison to the demand-side policies meant to increase access to mortgages. The government has consequently received poor performance reviews from the Federal Housing Advocate whose office was created by the 2019 legislation.

Moreover, promoting private home ownership without dealing with the affordability crisis may in fact further contribute to generational inequality. As Tranjan again points out in the Toronto Star, growing housing values have generated $3.2 trillion in capital gains for homeowners since 1977. That is capital income taxed at much lower levels than income from employment. Moreover, according to Statistics Canada, the children of homeowners are twice as likely to own their home as the children of tenants. If social mobility is slowing and inequality is deepening in Canada, housing is part of the explanation.

It’s easy to get lost in the nuance and complexity of housing policies, financial regulations, zoning laws, and the various other areas of governance that shape housing. Yet the primary issue is this: Canada’s housing system is geared toward profit-maximization. It’s the return on investment that drives decisions about what kinds of housing gets built and for whom. Under these conditions, it’s extremely difficult to reorient decision-making to prioritize social needs.

They may not be easy, but there are things that can be done to not only make homes affordable but to also change our relationship to housing.

At a bare minimum, governments must stop creating, and starting closing, the loopholes that allow landlords to escape rent control. Capping the annual growth in the price of housing is a proven method for generating stability in the rental market and protecting tenants. It also does not negatively impact the supply of housing, as some critics suggest. In fact, rent control could be strengthened and extended to contain price increases on vacant units and to prevent landlords from passing the cost of renovations on to their tenants.

Further, as the Canadian Union of Public Employees argues, we need to secure universal pension coverage with adequate benefits for all so that housing assets do not function as retirement plans. Without the guarantee of a secure retirement, it will be difficult to galvanize the public support necessary to bring down the price of housing and solve the affordability crisis. Abandoning home ownership under current conditions largely amounts to leaving workers exposed to the private rental market and the rapaciousness of increasingly corporatized landlords and developers.

The primary way to dig ourselves out of the housing crisis, however, is to build public, affordable housing, which requires taking on the vested interests that benefit from our profit-driven housing system.

There are plenty of examples from which to draw.

In the 1960s, the Swedish Social Democratic Party, through its “miljonprogrammet,” built a million homes in less than a decade to respond to the affordable housing needs of an urbanizing working class. Drawing on worker pension funds, the government constructed not just homes but whole communities as part of a vision of democratic socialism. One in four Swedes still live in one of these units today.

Closer to home, though admittedly less impressive, Canada itself used to build and maintain many more affordable housing units of different varieties. From 1964 to 1978, Canada constructed around 205,000 units of public housing, and from 1975 to 1984, encouraged the construction of 382,000 apartment units through rental supply incentive programs. Between 1973 and 1994, Canada then built or acquired roughly 16,000 not-for-profit or cooperative housing units per year.

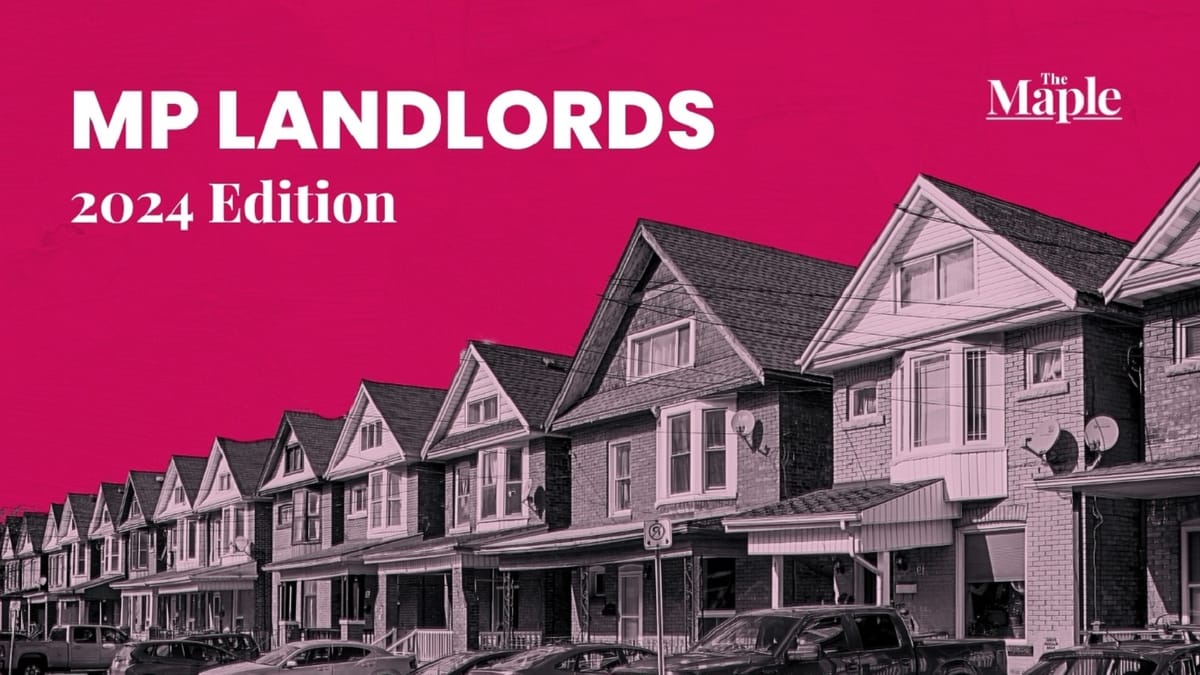

Yet, when 40 per cent of sitting MPs have real estate investments, it will require more than good arguments to return us to these levels of affordable housing construction and to win lasting change.

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- September 30 | A Strong Labour Movement Must Fight For Indigenous Workers

- September 24 | McGill Law Professors Have Launched An Unlimited Strike

- September 17 | Liberals Are Finding New Ways To Undermine The Right To Strike

- September 10 | Attacks On Fred Hahn Are Intended To Divide The Labour Movement