Almost two years into an ongoing pandemic that has infected 1.7 million Canadians to date, many labour organizers and economists are wondering how anyone could advocate against a permanent system of employer-paid sick leave for workers.

In British Columbia, 53 per cent of workers currently don’t have access to permanent, employer-paid sick leave.

Since May this year, workers who contract COVID-19 may take up to three days of government-subsidized sick leave if their employer does not already provide paid sick days. Employers must cover the cost of the sick days up front, but can then apply to be reimbursed for up to $200 per day by the government.

Meanwhile, the B.C. government is in the process of consulting stakeholders and members of the public as it prepares to establish permanent sick leave legislation, set to be launched in January 2022. However, business lobbyists are pushing against the proposal.

In the past 12 months, the B.C. Chamber of Commerce has been in communication with the government twice on the topic of paid sick leave. Back in May, the organization lobbied to suggest parameters for the COVID-19 paid sick leave program, pressuring ministers to ensure that the program was temporary, government-funded and easy to administer.

As recently as September 8, the B.C. Chamber lobbied in favour of pausing the implementation of the upcoming 2022 sick leave legislation to “extend consultation so that the program’s impact on business is fully understood before a decision is made.”

Some B.C. Chamber members have raked in substantial profits during the pandemic. Shoppers Drug Mart, for example, has been described as a “huge pandemic winner,” with same-store sales increasing more than 10 percent during the first quarter of 2020.

Similarly, B.C.’s Registrar of Lobbyists lists the Business Council of British Columbia as having communicated with Deputy Minister of Labour Trevor Hughes seven times in the past year on the topic of paid sick leave.

Those against paid sick days typically cite alleged employee abuse of time off and financial burdens on employers. However, David Fairey, a labour economist and research associate with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said these concerns are not justified.

“The evidence from jurisdictions where they’ve had paid sick leave legislation for many years is that workers that are entitled to paid sick leave typically did not use all of their entitlements,” Fairey told The Maple. “It’s a very small minority that might abuse them.”

Some business lobby groups want permanent sick-pay legislation to be delayed until after the pandemic, as recently reported by PressProgress.

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business, a non-profit organization dedicated to representing “small” enterprises, has urged the government not to introduce permanent sick days once the temporary program expires after December 31.

In a statement in May, CFIB provincial affairs director Annie Dormuth said: “The economic recovery of small businesses still remains uncertain and asking for their feedback on taking on additional costs right now is bad timing.”

Back in May 2020, CFIB asked federal and provincial governments and all political parties in Canada to ensure that COVID-19 related response measures are not made permanent until we return to “normal times.”

But, Fairey noted, a return to any semblance of normality does not eliminate the possibility of workers falling ill or getting injured. Fairey said COVID has merely opened our eyes to the rights workers deserve at all times.

“COVID has taught us that the issue of paid sick days is a public health issue,” he explained. “It should not be viewed as an employee benefit; it should be viewed as a public health and a human rights issue, because the actions of individuals who go to work sick impacts not only on their coworkers, but also their frontline workers; it impacts on the community that they live in.”

CFIB recently released a survey which suggested that small business owners cannot afford to pay for permanent sick leave programs. However, a May 2021 open letter from more than 60 B.C. employers from across multiple sectors to Premier John Horgan asked the government to implement paid sick leave during the COVID-19 pandemic “and beyond.”

“Please amend the Employment Standards Act to introduce a paid sick leave entitlement (or provision) for all workers, that lasts beyond the pandemic,” the letter stated.

Laird Cronk, president of the B.C. Federation of Labour, said it’s misguided to think that paid sick leave is a problem for businesses.

“It's actually a solution to a problem that never should have been there in the first place,” Cronk told The Maple.

Earlier this month, the B.C. Fed launched a digital campaign advocating for 10 days of paid sick leave.

CFIB’s opposition to paid sick leave is the organization’s latest stand against a long string of initiatives and policies aimed at protecting workers and boosting public programs.

CFIB has lobbied against increased contributions to CPP, as well as a small tax hike to fund improvements to public transit in Vancouver back in 2015.

Meanwhile, the group has lobbied in favour of tax cuts for “small” businesses — a demand called out by Gerard Di Trolio, a labour Ph.D. student at McMaster University, as a “euphemism for tax avoidance on the part of wealthy individuals that have incorporated themselves.”

CFIB members have also repeatedly spoken out against proposed minimum wage increases.

On the issue of Canada’s emergency pandemic response benefits in July 2020, CFIB argued that CERB hurt business owners by incentivizing employees to stay home rather than return to work.

However, Ian Robb, the Canadian director of Unite Here, a North American labour union that represents hospitality workers, attributed health and safety concerns — not CERB — as the main issue keeping employees out of the workplace.

More recently, CFIB also argued against the extension of CRB, one of the recovery benefit programs that replaced the initial $2,000 per month CERB in September 2020.

The Maple reached out to CFIB for comment on the implementation of permanent paid sick leave legislation, but did not receive a response.

In May, the Retail Council of Canada urged the B.C. government to “include all new or increased employer-paid COVID-19 leave” in the province’s temporary sick-pay reimbursement program, and to “create a similar reimbursement program for 2022 and beyond.”

Along with other business lobbyists, RCC signed a letter to the province last month asking that the implementation of paid sick days be delayed until after the end of the pandemic, and that the government provide “6 months or more notice of change to allow businesses to properly plan and budget for the additional costs.”

RCC describes itself as representing “over 45,000 independent, regional, national mass and specialty retail businesses and online merchants in general merchandise, drug and grocery.” While smaller brick and mortar retailers saw a decline in sales during the pandemic, sales for grocery and online merchants spiked significantly.

The Retail Council of Canada declined an interview request from The Maple.

The Need for Paid Sick Leave Done Right

Fairey said big business lobbyists are only considering paid sick days in terms of upfront costs, rather than the public health factor and its impact on workplace productivity.

“People who go to work sick spread infection to other workers and cause more sickness and more absenteeism,” said Fairey. “That reduces the productivity of the workplace. And workers who report to work sick are less productive than they are if they’re healthy.”

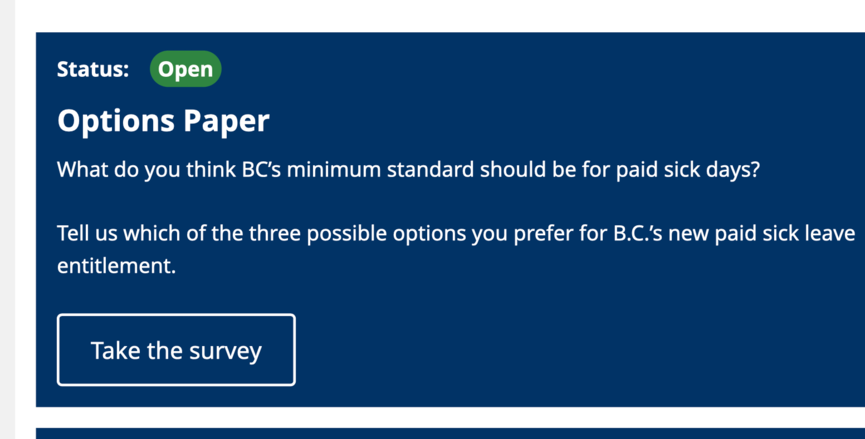

Now in the second phase of public consultation, the specifics of British Columbia’s upcoming sick pay legislation are still up in the air, but those advocating for workers’ rights are excited nonetheless.

“It's an idea whose time is long overdue,” said Cronk. “It's never made sense to have to choose between paying the bills if you don't have sick pay, and going to work and making others sick.”

The public has until October 25 to vote on the minimum number of annual paid sick days they would like to see legislated.

“(The survey) is one way to get opinions, perhaps, but it’s not a good methodology for the development of public policy,” said Fairey. “Public policy should be, in this particular case, based on good public health mitigation measures”

Fairey noted that those who doubt the severity of COVID-19 or other illnesses may be more inclined to vote against paid sick leave. He also highlighted the potential for survey manipulation, which may lead to unreliable results.

“You can respond to this survey as many times as you want to. Even if I am an employee, I can respond as an employer. Statistically, it is not accurate,” Fairey explained.

While Cronk and the B.C. Fed are pleased that the government is reaching out for input rather than writing legislation in the dark, he fears these decisions are being determined by a popularity contest, instead of adequate research.

“(The government) should look at what’s happening in other places where they’ve actually successfully implemented paid sick leave as opposed to relying on who presses a button on their keypad more often than others,” said Cronk.

Most developed countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development provide at least 10 paid sick days, Fairey said.

Additionally, Fairey said many jurisdictions have temporarily increased their sick leave allowances to grant paid time away from work to employees who have contracted COVID-19 — which requires an isolation period of at least 10 days.

“COVID has just put the issue on the agenda, and sparked the realization that our employment standards legislation needs to be modernized and updated to deal with this emergency and the ongoing spread of infectious diseases,” explained Fairey.

Ten days of paid sick leave would align with provisions in countries such as New Zealand and Australia, but fall short of stronger programs like Sweden’s 14 days and Germany’s 30 days.

Jasmyne Eastmond is a freelance writer currently based in Toronto. She received her BSc in Biology and English Literature from UBC and her MPhil in English (Criticism and Culture) from the University of Cambridge.