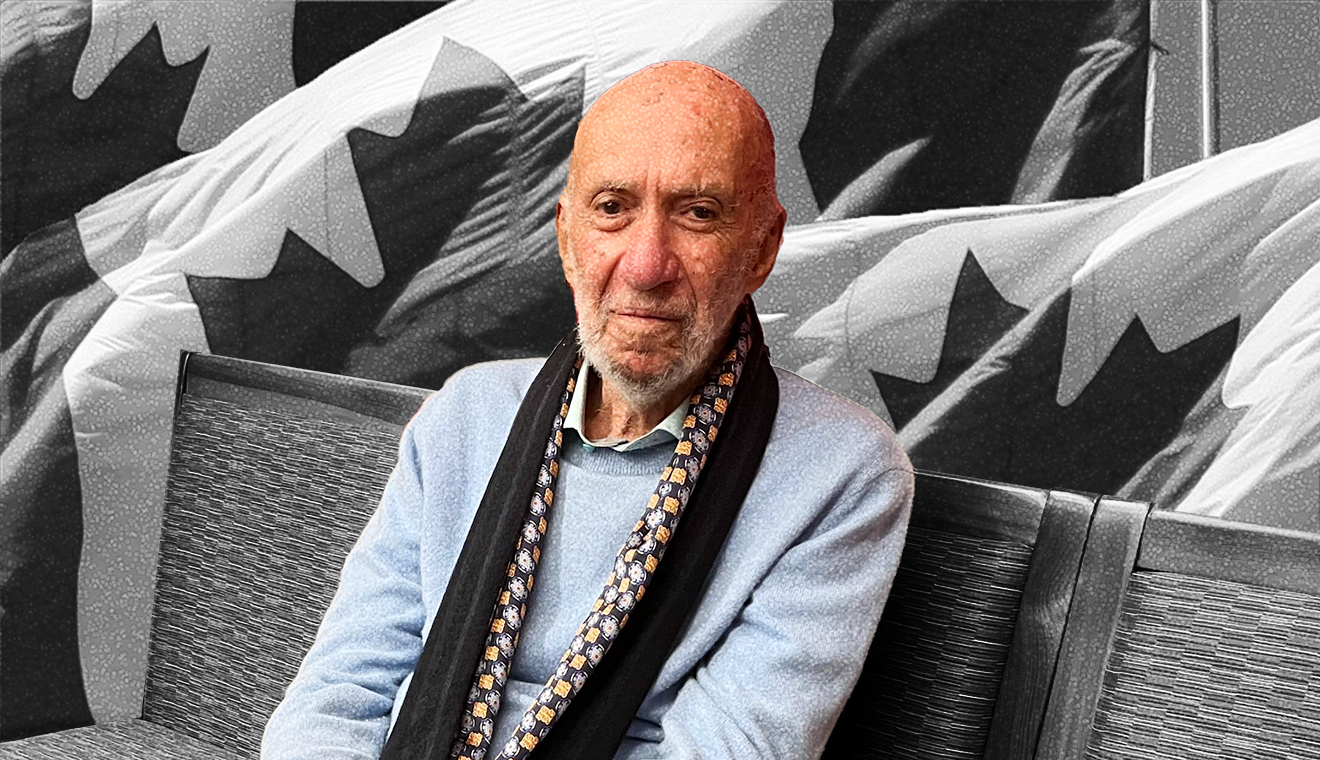

Richard Falk, a prominent international legal scholar and former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories, was invited to Ottawa last week to speak at a “people’s tribunal” on Canadian complicity in Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

A longtime advocate for Palestinian human rights, Falk is no stranger to hostility from Israel and its allies against his work. But what he and his wife and fellow scholar Hilal Elver experienced upon their arrival at Toronto Pearson Airport on November 13 was a first.

The couple were detained and questioned by Canadian border agents for approximately three hours. One immigration officer told Falk that he needed to determine whether or not Falk posed a national security threat to Canada.

November 13 also happened to be Falk’s ninety-fifth birthday.

Eventually, Falk and Elver were released and continued their journey to the conference in Ottawa.

I was also at the conference to provide a testimony on the Canadian government’s purchases of Israeli arms and military equipment. I sat down with Falk to talk about his experience with the Canadian immigration authorities and Canada’s broader complicity in the genocide in Gaza.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Alex Cosh: I wanted to talk about what happened to you and Hilal at Pearson airport. Can you give me a step-by-step of what happened?

Richard Falk: Well, at first, they somehow flagged my passport at immigration. The immigration officer told us, my wife [Hilal Elver] and I, and we went a long way within the airport, and then they put us at an empty desk. No one was there for a while, and they told us to wait. And they had taken our passports at the immigration entry point. And finally, some young, I guess, immigration security person came and said, ‘I have to ask you a few questions,’ or something of that sort, and that ‘we’re trying to,’ he added, ‘we’re trying to inquire whether you’re a threat to Canadian national security.’

At first I was sort of flattered by that. I’d never been told that in my long life. We answered a few questions like had I ever been to Canada before?, and was I being paid to participate in this conference? Who paid for my transportation? You know, questions of that sort. And then he left, as he said, ‘Oh, I have to talk to somebody about what we should do.’ And he left, and we waited there at this desk in a sort of empty room for an hour and a half, something like that. And my sense of being flattered wore off, and we knew we were missing this connection [to Ottawa], and we had been very tired. We had to get up at three o’clock in the morning in Santa Barbara in order to catch the Los Angeles flight to Toronto.

And we didn’t actually know whether there was space on the next Ottawa flight, or whether we’d have to wait until the morning, and we were scheduled to speak in the morning, so it was uncomfortable. Finally [the immigration officer] came back and said, ‘Well, we are still investigating whether you’re … a [threat to] national security,’ and he disappeared again. Another more than an hour passed, for no good reason. There was no complexity. He didn’t accuse us of anything. It was just more or less who we are. He was perfectly polite, but it was a very unusual performance.

AC: I believe they asked you if you support certain groups — did they ask questions of that sort?

RF: They asked me about this human rights group, Euro Med [Human Rights Monitor] where I’m the Chair of the Board of Trustees. [Euro Med has] been collecting useful information. They work basically with volunteer young people who do a lot of gathering data on the ground, and have been providing very useful inputs in various arenas concerned with these issues.

AC: I’ve cited them in my own work. It’s been really tremendous as a resource for data and evidence of what’s been happening on the ground in Gaza. I assume that at no point did the immigration officer specify how you might be a threat to Canadian national security?

RF: I was scared to ask them!

AC: I imagine so. And if I’m not mistaken, this was on your 95th birthday?

RF: Yes.

AC: I can’t imagine this is how you expected to spend your 95th birthday.

RF: It was bad enough making this trip that started in the middle of the night, and we were feeling sorry for ourselves before this all happened, and the only analogous experience I’ve had on my birthday is that once my son’s dog bit me very, very badly. I had to get 10 stitches at the nearby hospital. He’s a husky, and showed his vigour, though he was remorseful afterwards.

AC: Well, talking of otherwise friendly appearing creatures baring their teeth… you were telling me earlier about how Canada has, or had, a reputation of being a more reasonable broker in international affairs when compared with the United States. Would it be fair to say your experience was a first-hand encounter of the ugly truth of how Canada treats advocates for Palestine?

RF: Well, yes, at the interpersonal level. I mean, I was aware that Canada was an accomplice, an enabling accomplice, to the genocide and to generally supporting Israel, and I attributed it partly to its NATO membership and its desire to, in security issues, follow the U.S. lead.

I didn’t give it particular attention, because I was more or less focused on the actual interaction in Gaza and Israel with the U.S. angle.

AC: The immigration officers ultimately let you and Hilal continue your journey to Ottawa. You mentioned earlier that in your many years of speaking up very courageously on this issue, and being hounded by Zionist groups and the State of Israel, and being denied entry to Israel, you’ve never had this kind of questioning in Canada or the U.S. before.

RF: Yes, first governmental questioning, except in Israel itself. I went two or three times before I became [UN] Special Rapporteur [on human rights in the Palestinian Territories]. When I was special rapporteur, they pretended that I could come, but then they detained me in the [Ben Gurion] airport prison, basically, not for very long, and expelled me. And during the six years, I had to go to the countries bordering occupied Palestine: Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon. And it was itself a violation of Israel’s obligation to cooperate with the UN. And they were not so much after me, I think, but they were after the UN for appointing me. And so they tricked me into coming and then lied to the media, saying that they’d warned me not to come when their own ambassador had approved my agenda in Geneva.

And the New York Times published the official version, and when I said, ‘can I respond in some way by a letter or explanation?,’ they refused, which itself is sort of revealing this self censorship.

AC: During your tenure, Canada’s government was a hard-right, very pro-Israel Conservative government. The government of Stephen Harper distanced itself from your appointment as special rapporteur.

RF: They didn’t vote against me. They abstained in the actual vote, because if they had voted against me, it would be like a veto, because you have to be appointed by consensus for the first three years. The second three years is just a majority vote.

AC: You’re obviously paying much more attention to what’s happening in Gaza and the United States’ support for it. But based on what you’ve heard over the past couple of days at this people’s tribunal in terms of Canada’s ongoing complicity in the genocide, do you see anything has changed since those days of the Harper government?

RF: I think that on the issues, particularly that you addressed [on Canadian procurements of Israeli weapons], there isn’t much noticeable change. It may have changed the procedures to make them less visible and less explicit, but the fundamental connections have been sustained on private as well as public levels, and I think that’s true for the other liberal democracies that have tried to step back, but not too far. You know, they need to take about five steps back. And the U.S., of course, refuses to take even the half step. And that distinguishes it negatively from the rest of the West.

And of course, the Arab governments have a lot to be blamed for also because they have been passively complicit, and they have their own anxieties about any kind of people’s movement or popular movement, because they’re all pursuing policies that are not in accord with the views of the population or citizenry. So it’s a kind of series of powder kegs in these countries, and they count on the West, and particularly the U.S., to protect them against their own people.

AC: What do you see for the future of the Abraham Accords?

RF: I don’t know. There are reports that Trump is trying to promote the renewal of Abraham Accords initiatives. And I think there has been one success, Kazakhstan. But apparently the major Arab governments haven’t indicated one way or the other what they’re going to do. I doubt that under the present circumstances, either Saudi Arabia or Egypt will agree to the accords, probably and Jordan too.

AC: You mentioned earlier Canada’s embeddedness with the U.S. on security issues. But there have been signs of some strains with that in the past year or so. U.S. President Donald Trump has threatened to annex Canada. There was this initial rhetoric from Canada’s government; “elbows up” was the phrase. Do you see a future in which Canada and maybe some countries in Europe part ways with the United States, or do you see it essentially continuing as it always has done in the past few decades?

RF: It’s really hard. The crystal ball is very cloudy, and there are so many uncertainties, and I guess one can put that among the uncertainties, that there could be a fundamental kind of realignment. See, I think Trump’s real interest is to have the three geopolitical actors run the world: China, Russia and the U.S., and to bypass Europe and the rest, and this will put pressure, I think, on Europe — and in a different way, on Canada — to whether they should sort of accept this kind of restructuring of international order, which would involve the marginalization of NATO and so on.

And for Canada, they’re caught between following Europe and following the U.S. And how they resolve that dilemma, maybe trying to please both and ending up pleasing neither, is one scenario that shouldn’t be overlooked. Canada in that way has not been challenged to play an important independent role. It has been content to be in the shadow of the U.S., and it reacted a little bit, as you suggested, to Trump’s wanting the shadow to extend to the 51st state, which was, you know, a completely incredible Trumpism. But in addition to MAGA, I don’t know if you heard the acronym “TACO.” Trump always chickens out.

And the Democratic leadership is terrible in the U.S. It’s scared of its own shadow, and tries to please a sort of non-existent centre at a time when the society is deeply polarized on these issues, and has no leadership, no credible leadership.

AC: What did you make of the recent election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York City? Did that give you some optimism?

RF: Yes, his parents are friends of mine. In fact, they rented our house in Princeton when we were still in Princeton. And I’ve known him [Zohran’s father] Mahmood Mamdani for a long time. It was a true glimmer of light in a dark sky. And I was astonished that [Zohran] was successful at the primary stage.

And again, the Democratic leadership failed to take advantage of what he represented, and really alienated rather than accommodated this hopeful development, and we’ll see what happens. I mean, his message is a very important one and he seems very talented as a young political figure.