Hi there, it’s Adam King again, back to continue my course on Canada’s welfare state.

In the last lesson, I gave you a brief history of the welfare state and social democracy in Western Europe and North America. We also conceptualized the purpose and politics of the welfare state.

In this lesson, I’ll be going over Canada’s existing welfare state to give you a better understanding of what we currently have, and how it has been shaped by federalism and eroded by neoliberalism

As you’ll see, although aspects of the welfare state are worth celebrating, in many other ways it falls far short of what workers and their families need.

Social Welfare and Canadian Federalism

In the first lesson of this course, I gave you an overview of sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s three types of welfare states: liberal, corporatist and social democratic. You’ll recall that Canada is a country with a liberal (or “liberal market”) form of welfare state. This means that Canadian social policy tends to target benefits to the poor (rather than pursuing universality), rely on the private sector and employers to provide many benefits (such as extended health care plans and pensions), and, overall, maintain comparatively low levels of social expenditure.

However, Canada’s welfare state also has an additional debilitating feature: the division of powers and responsibilities between levels of government. Most notably, this takes the form of federalism, wherein the federal and provincial governments have distinct and mutually exclusive legislative powers.

This division of powers is largely the result of the ‘bi-national’ and bilingual composition of Canada — i.e., accommodating Quebec’s desire for political autonomy. However, the result is that all provinces ended up with power over vast areas of governance, which has often created a lack of uniformity across the country on social policy.

Without delving too deeply into federalism’s legal intricacies, we can note that “interjurisdictional immunity” dictates that where one level of government (e.g. provincial) “occupies” a legislative “head of power,” the other (e.g. federal) has no jurisdiction. Canada’s constitution, for example, gives legislative power over “property and civil rights,” which is interpreted to include employment and social policy, to the provinces, except in a few select areas.

At certain points in Canadian history, federalism produced progressive outcomes. For example, in 1962 public health insurance covering all medical services was first introduced in Saskatchewan, where the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the precursor to the NDP) had held power since 1944. In this way, universal health care was first rolled out in the provincial homebase of “agrarian socialism” before being implemented nationally. By 1971, after the passage of the National Medical Care Insurance Act a few years prior, each province had its own single-payer, Medicare program, funded collaboratively with the federal government.

However, such examples are rare. It has been more common for the lack of federal authority over social policy to impede the growth of the welfare state. For example, the political scientist Barbara Cameron details how the Canadian state struggled throughout the Great Depression to introduce progressive economic policies on the order of the “New Deal” then being implemented by United States President Franklin Roosevelt. Again, the reason boiled down to provincial authority over most legislative aspects of the welfare state.

This partly explains why many of the key social policies of New Deal-style social democracy were introduced much later in Canada than in the U.S. Perhaps most noteworthy is the case of unemployment insurance. Initial attempts to create a national unemployment insurance program were struck down as unconstitutional because they supposedly overstepped the federal government’s legislative authority. It wasn’t until the program could be framed as a matter of ‘monetary policy’ (where the federal government has clear authority) rather than social policy, that Canadian workers across the country gained access.

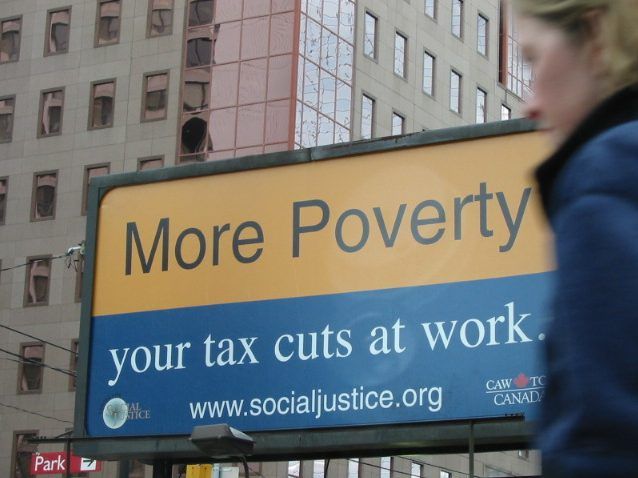

The Impacts of Neoliberalism

More recently, the growth and spread of neoliberalism have further undermined federal and provincial governments’ commitment to social reform. Before turning to the various programs and policies that constitute Canada’s remaining welfare state, we should, therefore, first take stock of how neoliberalism has eroded social welfare.

The first thing to note is that rightward political and economic shifts have been especially harmful to the labour movement — historically, the social base responsible for expansions of the welfare state. Although Conservative and Liberal politicians haven’t completely undermined the labour movement in Canada, they have nevertheless significantly reduced its power, through free-trade policies and deindustrialization, the use of back-to-work legislation and other draconian curtailments of collective bargaining rights, and a refusal to reform labour law to address the growth of hard-to-organize service sector employment.

Second, neoliberalism has transformed the overall orientation to social welfare, in Canada and beyond. Rather than view the social welfare state as a set of institutions meant to create a foundation of material security and economic rights, neoliberal politicians view it as an economic burden to private sector innovation and a barrier to labour market activation.

Across the country, we’ve seen governments privatize areas of social welfare provision, shift responsibility for unemployment or other social hardships onto workers, and generally cut back on social expenditure. What’s commonly referred to as “workfare” — making social support so meagre that people are forced to accept whatever work they can get in order to survive — now seems to be the guiding orientation of a once more generous welfare state.

As we review the various public services and income supports still present in Canada’s welfare state, what neoliberalization looks like in practice will become clearer.

Last — and directly related to the problem of federalism — neoliberal changes to the welfare state have been facilitated by restructuring and reducing the social and health transfer payments that the federal government provides to the provinces.

In a country as geographically and economically disparate as Canada, federal transfer payments are a vital revenue source for many provinces. As these are cut, cash strapped provinces then download responsibility for various areas of service delivery to local municipalities, who have very limited revenue generating capacities (outside of property taxes and minor things like parking fees).

The result is one big responsibility shift, wherein lower levels of government must take on greater service provision without the funding or revenue to do so. Of course, the whole arrangement ultimately leads to service cuts, which is likely the point.

Canada’s Liberal Welfare State

Despite these quite serious structural weaknesses, Canada nevertheless retains features of a successful welfare state.

In the previous lesson, I made a distinction between the two main functions of the welfare state: non-market public services and income transfer programs. Let’s look at a selection from each category and see how they stack up, comparatively.

Public Services

In many respects, Canada maintains fairly strong commitments to our vital public services, such as healthcare and education, despite them facing political attacks and budget cuts from various levels of government over the past several decades. They are both overwhelmingly popular with the public, making it quite difficult for governments to dig the knife of austerity too deep.

It’s safe to say the pillar of Canada’s welfare state is the single-payer, Medicare system. Medicare developed in two stages: first, public insurance and funding for hospital and other diagnostic care in 1957, and eventually full public insurance for all doctor and medical services in 1966, as noted above.

However, many problems persist in healthcare funding and policy. Most importantly, key areas of care, such as dental, optometry, pharmaceuticals, mental health services and many forms of necessary physical therapy, aren’t covered by provincial health insurance plans. As well, elderly care remains a patchwork of public and private providers, with awful outcomes for some of Canada’s most vulnerable seniors (more on this in the next lesson).

Reforms to the cost-sharing agreements between the federal government and provinces over the years have also caused major issues, particularly for hospital funding. The move away from 50-50 cost-sharing toward lump sum federal payments based on average gross national product has been in keeping with the general trend of reducing federal social welfare funding.

Canada’s healthcare spending remains among the highest in the world, comparable to other developed countries with universal healthcare systems. Many of these countries, however, also cover services Canadian Medicare does not.

Let’s turn to education. Public education funding levels and formulas vary across the country, with some provinces providing greater contributions for disadvantaged students and communities, while others allocate more for capital investments.

On average as of 2020, the provinces and territories were spending about 4.09 per cent of their GDP on public education. This represents a considerable drop from previous decades: According to the World Bank, in 1971 Canada was spending 7.7 per cent of GDP on education. Canada’s education spending also lags compared to other developed (and more social democratic) countries. As of 2017, Norway was spending 7.9 per cent of GDP on education, while Denmark and Sweden were spending 7.8 and 7.6 per cent, respectively.

Additionally, our current national funding average somewhat hides the reality of spending cuts because Canada’s northern territories spend disproportionately high levels on education (5.8 per cent of GDP in the Yukon and Nunavut, and 4.8 per cent in the Northwest Territories.) When the territories are excluded, the national average drops to a low of 3.68 per cent.

The national spending average also obscures considerable funding variation across the provinces, from a high of 4.7 per cent in Manitoba to an embarrassingly low 2.6 per cent in British Columbia. In B.C.’s case, years of spending cuts have produced serious problems in education.

Moreover, once this type of public austerity becomes embedded, it has far-reaching and long-term negative consequences. For example, as of 2019, per-pupil funding in B.C. sat at approximately $1,800 less than the national average, largely the result of education funding dropping from 20.3 per cent of the province’s annual budget in 2000-01 to only 11.3 per cent in 2019-20. As a result, by July 2017 B.C. had a repair and maintenance backlog of more than $5 billion. By 2019, 87 out of the 110 schools in the Vancouver District School Board were classified as in “poor” or “very poor” condition.

When it comes to higher education, the picture is much worse. Unlike many European countries with tuition-free higher education, Canada persists with a subsidized model wherein government revenue and student tuition fees (often financed through public and private student borrowing) fund post-secondary schools.

The general trend in higher education funding has been to shift more of the cost onto students and their families through increased tuition fees. In 1990-91, the average tuition in Canada was $1,464. As of 2020-21, that figure had jumped to $6,580, a nearly 450 per cent increase over 30 years.

This significant rise is the result of federal and provincial government neglect. Despite huge growth in student enrolment, federal government transfers to the provinces for post-secondary education have declined from 0.5 per cent of GDP in 1983-84 to 0.19 per cent in 2018-19. Meanwhile, the provinces themselves are spending far less on higher education, both as a percentage of GDP and as a share of total government expenditures.

Much like other educational spending, provincial variation creates uneven services, in this case in the form of much higher tuition levels in certain provinces. For example, average tuition in Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan in 2020-21 was $8,757 and $8,243, respectively, while Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador charged on average $3,155 and $3,036 respectively.

The most glaring absence when it comes to public services in Canada is the lack of a universal childcare system. In their most recent federal budget, the Liberal Party promises to spend $30 billion over five years to create one. We’ll see.

Income Transfer Programs

In the previous lesson, I argued that we can conceptualize income transfers as a way to redistribute labour income from those currently working to those who aren’t in paid employment — whether labour market exit is temporary or permanent.

The primary program for accomplishing this income transfer has been unemployment insurance (UI), called Employment Insurance (EI) in Canada since 1996. The EI program also pays out maternity and parental benefits, as well other long-term sickness and care benefits. Although EI establishes a decent floor of income security, in many respects the program is seriously inadequate and compromised.

Throughout its history EI (and previously UI) has undergone a series of changes dealing with eligibility criteria, coverage and benefit levels. When UI was created in 1940, the eligibility rules meant that it covered about 40 per cent of workers who experienced unemployment. After expansions in the '50s, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government reformed the program to cover more than 95 per cent of workers in 1971, while adding maternity and sickness benefits for the first time.

However, beginning in the late '70s, governments started to raise the number of “insurable hours” workers needed to qualify for benefits. As well, eligibility rules were changed to reflect differences in regional unemployment. Workers in regions with lower unemployment then had to have more insurance hours to access benefits, a practice which continues today (these can range from 420 to 700 hours, depending on your location).

The EI funding model was also changed. Prior to 1990, EI was funded through employer and employee premiums (paid as a percentage of gross income) and general federal government revenue. However, in 1990 the federal government stopped contributing to the fund, while both the Conservative Brian Mulroney and Liberal Jean Chrétien governments progressively reduced benefit levels over the course of the decade.

The cuts to EI went well beyond reduced benefits, however. Governments also started to raid the EI fund, effectively taking employer and employee contributions and using them as general government revenue (to the tune of more than $57 billion by the Stephen Harper years).

The emaciated EI program covered around 42 per cent of workers who contributed to the program as of 2018, paying an income replacement rate of only 55 per cent of prior earnings (up to a maximum of $595 per week). However, we should also note that 36.1 per cent of workers were “non-contributors” to EI in 2018, meaning they were relegated to some type of nonstandard employment where it wasn’t being deducted. They too were ineligible for benefits.

Canada’s system of retirement benefits consists of the Canada (and Quebec) Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS). The former is an earnings-based, social insurance program made up of employer and employee contributions; the latter is a much smaller ($626.49 per month maximum), though universal, payment that is made to Canadians 65 and older. Some low income seniors receiving OAS also earn a Guaranteed Income Supplement (ranging between $563.27 and $935.72 per month), which has contributed to reducing elderly poverty, though more could be done.

The CPP functions as a retirement benefit based on a worker’s average previous income and contributions to the program. Currently, these payments range between $679.16 and $1,154.58 per month, for those 65 and older. “Enhancements” passed in 2017 will raise the percentage of employer/employee contributions as well as the level of earned income subject to CPP premiums. These changes are meant to expand and improve the program. As we’ll see in the next lesson there’s still much to be done on this front to make retirement secure.

Next, we have social assistance (or “welfare”) and disability support programs. These are administered by the provinces in concert with municipalities, and with reliance on federal social transfer payments.

Social assistance programs are perhaps the weakest aspect of Canada’s welfare state, which is in good part the result of how stigmatizing it is to be poor in this country. Benefits levels are shamefully low and geared largely toward pushing people back into the low-wage labour market, irrespective of their life circumstances.

For example, recipients of “Ontario Works” receive a basic benefit of $733 per month, usually with various “work ready” requirements attached, such as attending resume writing or job counselling workshops. The Ontario Disability Support Program, on the other hand, provides $1,169 per month in basic benefits to those with an “assessed disability” and demonstrated financial need. In both cases, additional support is provided when children are in the household.

Such programs clearly fall far short of providing any semblance of economic security. They are, rather, creatures of neoliberal austerity and the shift toward “workfare.” The story is much the same across the country.

Finally, there is the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), paid for every child under 18. The CCB amount is based on the number of children and their age, as well as the applicant’s marital status and net family income. The maximum benefit level is $569.41 per month for each child under six, and $480.41 for those between six and 17. Additionally, some families are entitled to the Young Child Supplement (a maximum of $1,200 per year per child) for children under six, while children with “severe and prolonged” disabilities may also receive a Child Disability Benefit of up to $242.91 per month.

It’s unsurprising that our most robust and successful income transfer program is the child benefit — it’s as close to a universal benefit as we have. Because it has no work requirement or income threshold, all families with children receive it, which ensures the poorest children gain access. Were it targeted specifically at the poor, like most other income transfer programs, it too would probably be stingy and ineffective.

Although there are some solid foundations on which to build, Canada’s welfare state is in significant respects structurally limited and enfeebled by underfunding and neglect. Core programs like Medicare and public education remain popular but need protection and expansion. Some income transfers, such as the CCB, pursue universality and greatly help in the fight against child poverty, while others, like provincial social assistance, are so low that immiseration is all but guaranteed.

Federalism and neoliberalism pose challenges to reform, but they aren’t insurmountable. Labour and the left have successively won life-saving social democratic programs in the past and could do it again, with sufficient organization and power.

In the next lesson, we’ll explore how we could reform Canada’s current welfare state, and what policy principles should guide those changes.

Thanks for reading,

Adam