In 2012, the Ontario Provincial Police seized $10,000 directly from the pockets of North Bay, Ont., man, Jason Paquette, during a random street search. He hadn’t been charged or convicted of any crime in relation to the money — his only recorded conviction had been drug possession charges from several years earlier — and there was no evidence of connection to criminal activity. Paquette said he’d been saving the money to buy a car.

Paquette wasn’t charged or convicted of a crime at any point in this process, yet what the Ontario government was doing was legally permissible due to a practice known as civil forfeiture, which allows police to seize cash, property or goods suspected to be associated with criminal activity. It’s part of the legislation in all provinces except for Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland.

Like many carceral policies, civil forfeiture has been presented to the public as something used to punish criminals and keep civilians safe. The Department of Justice, for example, defends civil forfeiture by claiming that it can: “remove the incentive from engaging in unlawful behaviour”; “finance the prevention and control of organized and other crime”; “mitigate the damage to the economy occasioned by the large volumes of untaxed profits in the illicit marketplace.”

In reality, the practice is largely unregulated, as the only justification needed for a legal act of civil forfeiture is for the property in question to have possibly been used by someone, at any point, as an instrument of crime (regardless or whether or not the owner has been charged with, much less convicted of, that crime.)

Police have been known to seize cars, computers, cash and even entire houses. In 2018, British Columbia’s government seized more than $3.3 million in cash alone, as well nearly 300 vehicles, and more than 500 phones, tablets, and computers.

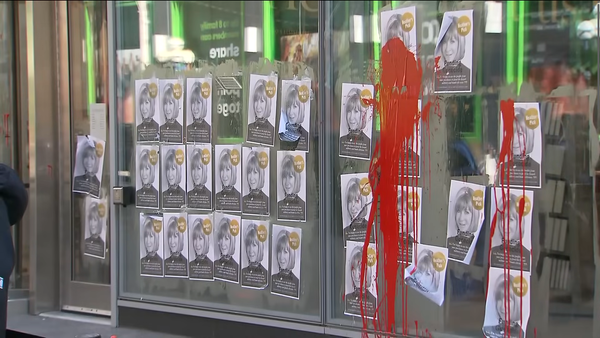

In overpoliced neighborhoods such as Vancouver’s Downtown East Side or Toronto’s Regent Park, where community members, especially racialized people, are disproportionately criminalized, essentially anything is up for grabs.

The most common argument against civil forfeiture is that its vague regulations end up harming innocent people. The most commonly suggested solution is to tighten the requirements for what constitutes a legal forfeiture. However, the reality is that civil forfeiture is fundamentally unjust regardless of who it impacts.

Drug users, sex workers and other criminalized people don’t deserve to have their property stolen by the government. Exacerbating the cycle of poverty in criminalized communities isn’t ever morally or logically justifiable.

In order to justify civil forfeiture, you have to say explicitly what is implicitly written in the letter of Canadian law: Criminalized people aren’t deserving of freedom, autonomy or equality. The only solution to the problem of civil forfeiture is to abolish it entirely.

Civil Forfeiture And The Non-Profit Industrial Complex

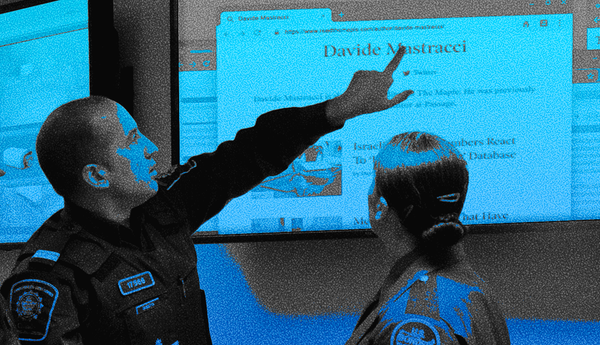

In all provinces where it’s legislation, a significant amount of civil forfeiture money is funneled directly back into the police force for increased manpower, special programs and amenities. Ontario’s civil forfeiture money, for example, is partially used for the Civil Remedies Grant Program, exclusively available to police to fund new initiatives.

However, police and government tend not to publicly focus on this use of the money, instead trying to frame civil forfeiture as a charitable process. Some provinces, like B.C. and Alberta, do redirect the majority of their stolen capital into community organizations and nonprofits through civil forfeiture grant programs. Others, such as Ontario, redirect a negligible amount.

Regardless, police are able to make civil forfeiture more popular than it otherwise would be by entangling it directly with the non-profit industrial complex. B.C.’s grant program, for instance, is a source of funding for organizations across the province, providing 2019-2020 annual grants that ranged from $20,000 to more than $300,000 in categories such as Indigenous Healing, Restorative Justice and Sex Worker Safety.

The ultimate irony here, of course, is that the money being funneled into these government-approved Indigenous and sex worker safety programs has often been stolen directly from the hands of Indigenous people and sex workers. Police have criminalized sex work, stolen the homes, livelihoods and transportation of those sex workers through civil forfeiture, and then proceeded to use a portion of that money to provide institutionalized funding for the problems they caused.

Prominently Indigenous neighborhoods are among the most heavily policed in the country, and the police play a direct role in the colonial destruction of Indigenous culture, and yet provincial governments have the gall to use money stolen from Indigenous people to pretend they care about reconciliation?

The ultimate function of civil forfeiture is not to protect sex workers, drug users, Indigenous or racialized people, or any other marginalized group, but rather to use their continued subjugation as fodder for a police profit machine.

Breaking The Dependency

Many of the nonprofits funded by civil forfeiture money provide essential supports and services. Removing these organizations from the community by defunding them would be harmful, something police cynically use to their advantage. There’s no more effective or cruel way to ensure the continuation of civil forfeiture than by creating a system wherein marginalized communities seem to need it to survive.

By entangling themselves with the police, organizations that engage directly with marginalized and criminalized people are limiting their ability to do meaningful work. They will only be able to truly serve their communities when they aren’t indebted to the police. But this can’t be fixed in half measures: We must demand nothing less than police department budget cuts and ending civil forfeiture for now, with the eventual goal of the total abolition of the prison industrial complex.

For example, the 2020 annual Vancouver Police Department (VPD) budget is more than $314 million, making up 21 per cent of the city’s total operating expenses. Meanwhile, in recent years, between $5 to 8 million has been funneled into community organizations annually through the civil forfeiture program. That means a mere 2.5 per cent VPD budget cut could allow for the elimination of the civil forfeiture program without losing out on any community support.

If we begin to defund the police and redirect funds into specialized care and response networks, there will be more than enough money available for the nonprofits currently caught in a carceral stranglehold to survive. The work to make this possible is already being done across the country, including by Vancouver’s Defund VPD Network, the Toronto-based Black Lives Matter and local organizing.

It’s time for Canada to completely abolish civil forfeiture, reimburse those who it has stolen from, and redistribute police funding to grassroots community organizations as reparations for the incredible damage the project has done.