When M.H. and her neighbours faced regular water shutoffs, they went door to door in their 12-storey condo building. One of her neighbours was involved with the Toronto Centre Tenant Union, and suggested they canvas the building to see if others were also annoyed.

They asked, “Hey, is anyone else unhappy? You want to sign this petition to ask for better communication?,” according to M.H., who is not being identified to avoid being labelled a problem tenant by future landlords. “That was it.”

One woman yelled at them, saying she disapproved of their canvas and found them ridiculous.

Another woman posted in their building’s Facebook group, implying that the tenants’ campaign could decrease the value of her condo, according to a copy of the post seen by The Maple.

M.H. and her neighbours had come face to face with one of the biggest hurdles to organizing campaigns in condo buildings: owners and tenants live in the same building, and their interests are often in conflict.

There are countless other ways that Canada’s condo boom has affected community organizing and political campaigns.

Condo renters tend to be richer, more transient and more apathetic than other tenants, statistics and political organizers say. They cannot be united against a common foe because they all have different landlords.

And condo buildings themselves are often designed to keep outsiders away: some require a different fob to access each floor, and nearly all condo buildings ban door-to-door soliciting. Political candidates are legally allowed to enter condo buildings during election periods, but gaining access is often practically impossible.

“It is changing how our democracy works,” said Dylan Webb, an NDP campaign manager and riding association president in British Columbia.

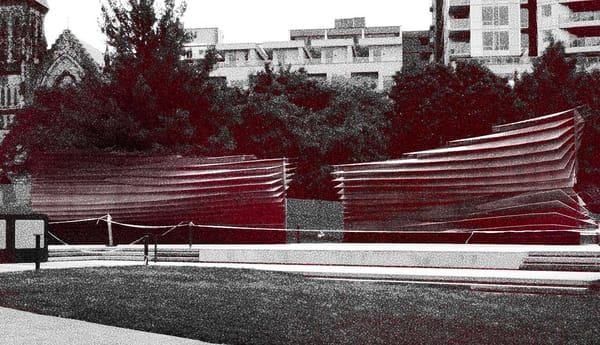

Even the sterile aesthetic of condo buildings can be dispiriting to organizers.

“Personally, I hate canvassing in buildings, especially condo buildings, because they are so monotonous and everything looks exactly the same,” said Nigel Morton, an organizer who has worked with Davenport For Palestine, TTCriders and local NDP campaigns.

But political organizers are adapting, trying out new tactics and persevering through the “bullshit” in condo buildings for rewarding one-on-one connections.

The ‘Condo Class’

At least 15 per cent of occupied dwellings in Canada are condos, according to the latest available data from Statistics Canada.

Condos are concentrated in big cities, making up 32.5 per cent of all homes in Vancouver and 24 per cent of all homes in Toronto.

Smaller cities like Hamilton, Ont. and the Tri-Cities of Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam and Port Moody in British Columbia are also seeing between 1,000 and 4,000 new condo units built every year, according to data from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

The classes of people that own and rent condos are distinct. Those who own condos have historically had lower incomes and fewer assets than people who own detached houses, according to Statistics Canada data from 2000 to 2011.

Those who rent condos, on the other hand, are younger, have higher incomes, higher-status jobs, and more education than typical renters, research from the University of Toronto found, citing 2016 data.

Yet Ontario’s condo renters face more precarious conditions than other renters, the paper noted, because their landlords can kick them out without rehousing them, while owners of large rental apartment buildings cannot.

Condos are “the hyper definition of private space,” said Matthew Green, the former NDP MP for Hamilton Centre who lost his seat in an upset in the April federal election. “Developers, slash landlords, slash the corporate class, have overcome the threat of community organizing for collective good within these spaces.”

Green regularly organized ice cream socials with tenants in traditional rental buildings and even helped organize a tenants’ union while campaigning for city council in 2014. But during his most recent campaign, about six condo buildings in his riding shut him out.

“These aren’t medium-rise apartments. We’re talking 20, 30 storeys. Like, thousands of high-density people we could not get a hold of,” Green said. “There’s no connecting with them except for mass media or digital media, both of which we were just woefully behind Liberals and Conservatives.”

In the riding of Coquitlam–Port Coquitlam, Webb said he sometimes finds it easier to send canvassers to houses than deal with the headache of trying to gain access to condo buildings. “I live in one of these fob buildings. And not one candidate ever has been to our building,” he said.

That lack of in-person engagement is dangerous, he said.

“When you’re out there in the rain, even people that are not of your political persuasion will be more open to hearing you. The reduction of the human element, and replacement of it with the algorithm, is one of the big dangers of this.”

Condo renters have also tested the traditional definition of gentrification.

Historically, gentrification has referred to the process of a neighbourhood’s renters being replaced by owners. But condo renters moving into newly built residences can displace their neighbours by driving up rent prices, the University of Toronto paper explained.

At the same time, the condo renters themselves are often facing poor conditions.

“We have a weird mix of people who’ve been living in the neighbourhood for 20 years losing their homes and people who come into overpriced condos, then find that everything is falling apart,” said Mel B., an organizer with Vancouver Tenants Union’s Joyce-Collingwood chapter.

Mel B., who is not being identified by her last name because she’s trans and not out to everyone in her life, said about five condo tenants have reached out to her chapter of the Vancouver Tenants Union for help with their landlords.

The union tried to help, but hit a number of barriers. Normally, the union uses public records to find out who owns a tenant’s home and then identifies what other properties the landlord owns. But public records only list if a person owns a unit in a condo building, not how many units they own. That means they couldn’t identify other tenants with the same landlord.

“A lot of the tenants end up not wanting to do a bigger fight because they feel so alone,” she said.

The union is brainstorming new tactics. One idea, which hasn’t yet been tested, is to organize around common issues instead of common landlords.

M.H. tried to do that when her water was shut off. But she found that each renter, because they had different landlords, had a different experience.

M.H. and her partner both work from home and went full days without being able to refill their water glasses, use the toilet, make coffee or cook. This happened eight hours a day for almost three weeks in total, spread out over five months.

While some of her neighbours’ landlords gave them a month of free rent, M.H.’s landlord only offered a small discount. She spent months negotiating with the landlord over email.

M.H. even found a condo owner in the building who was willing to write to her landlord on her behalf, sharing that she had paid for alternate accommodation for her tenant during the water shutoff.

Rather than be moved to abate M.H.’s rent, her landlord blasted the person who sent the email in a social media group.

That made M.H. feel “scared, intimidated” and “upset,” she said.

M.H. eventually came to an agreement with her landlord. But she still feels vulnerable in her building because of her experience with door knocking. “I live with these people …. After I knock … after this post, they still will recognize my face, and they can talk to me at any time.”

Chased Out of The Building

The nasty reaction of some of M.H.’s neighbours is typical in condo buildings, organizers say. Because canvassing is generally not allowed, some condo residents become aggressive when political campaigners do show up.

“Like 10 per cent of people are pretty outraged that you’re in the building,” said Webb, the NDP campaign manager in B.C. “There’s people that are literally chasing you out of the building. And then there are people that are like, ‘Oh, my God. This is the first time I’ve ever had a politician come by.’ And that creates an easier win.”

Morton, the community organizer in west Toronto, said that the high turnover in his riding’s condo buildings have completely disrupted the concept of community organizing.

“Community organizing relies on the fact that people are in the same place, are being affected by the same things, and want to make the same changes,” Morton said. “If that’s changing all the time, it makes it tough to build together.”

But he recalls that Davenport For Palestine found a new member during one condo canvas — before they were booted out of the building.

“It absolutely happens and is worth it. That’s why you keep dealing with the bullshit of trying to get into these buildings, because there are people worth reaching out to and talking to, and are ready to engage.”