In the early morning of November 27 in downtown Quebec City, Pacifique Niyokwizera was beaten by police. They punched him and kicked snow in his face, leaving him with several broken blood vessels in his left eye. The assault on Niyokwizera, 18, may have never made headlines had it not been for the fact that it was recorded.

Niyokwizera and his friends had just been inside the famous Grande Allée bar Dagobert. They were waiting for a ride when police hassled them to leave the street. The group moved to a parking lot where police followed them and escalated their harassment to violence. Niyokwizera was then put into a cruiser and driven a few blocks away without his coat, cell phone or wallet, according to his lawyer.

The video of the assault went viral. Politicians were quick to react, including Quebec City’s new mayor Bruno Marchand. Having only been elected earlier that month, this incident was Marchand’s first major crisis, but it wouldn’t end there: Five police officers ended up being suspended with pay, and two investigations were started into the events of that night.

The police never could explain why they harassed and detained Niyokwizera. In the press, there were allusions made to something having happened inside the Dagobert, and police claimed they responded to a call from bar staff about Niyokwizera and his friends. But the owner of the Dagobert told Le Devoir that never happened. While he said that Niyokwizera’s friends had been asked to leave after a confrontation, he added that his staff hadn’t called the police. Niyokwizera even came back the day after to apologize to bar staff for his friends causing them trouble the night before.

Two more videos came out that following week, all showing violent altercations between police and people within bars in Quebec City. One of the videos was from the same night as the attack on Niyokwizera but in Sainte-Foy, about a 15-minute drive from the Grande Allée.

And on December 2, a fourth video was circulated, this time showing police throwing a man against the wall in a hallway at a bar located in Quebec City’s lower town on October 16. The incident started with police asking where the man’s mask was (in his coat pocket) and ending with him nursing a serious concussion. One police officer in this video had already been suspended due to his involvement in at least two of the incidents the other three videos captured.

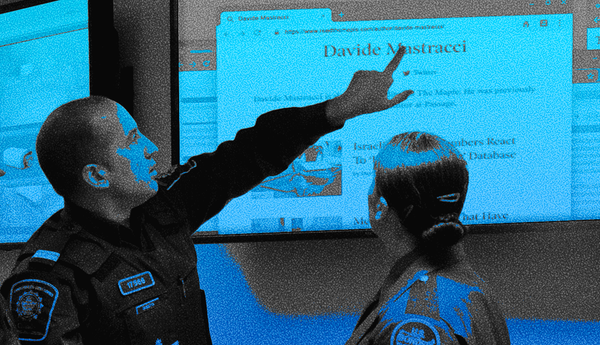

Police public relations wasn’t looking good. The police fraternity insisted the videos were taken out of context. Media attention was universally negative toward the police. A GoFundMe for Niyokwizera had surpassed an initial goal of $25,000 within 24 hours, and a rally was called for December 4 outside the National Assembly to condemn police brutality. So, police did what they usually do in a situation like this: they searched for something they could use to turn the victims into criminals, and they found it with one of Niyokwizera’s friends.

The day before the rally, news broke that a 19-year-old friend of Niyokwizera, who was present when police attacked him and defended him in the media immediately following the event, was arrested. The friend was charged with sexual assaulting two people. Radio-Canada reported that the events in question happened in August, and that the police started investigating a month later, after one of the alleged victims complained.

The next day, the Journal de Québec published an article that included a video clip the friend had posted to social media, showing him posing with a gun. The article also referenced his connection to Niyokwizera’s arrest in the headline.

Public Safety Minister Geneviève Guilbault insisted that the arrest wasn’t in retaliation for the friend’s public profile after Niyokwizera’s detention. She told journalists that if he was arrested, there must be proof, and that her thoughts are primarily with his alleged victims.

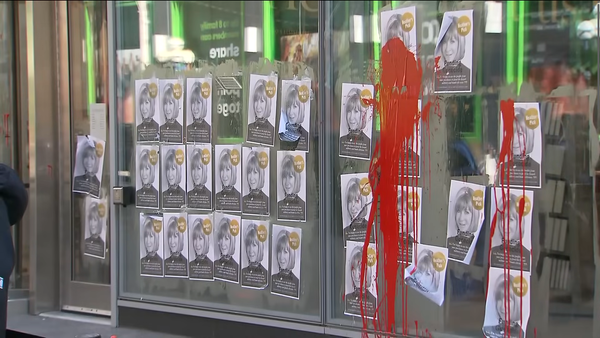

Rally organizers first decided to cancel the event, and then to make it more about police brutality in general and less about Niyokwizera specifically. Sol Zanetti, MNA for Québec solidaire (and a friend of mine) posted on Twitter that he was removing the donation he had made to the GoFundMe. Quietly, in private messages, I heard from people who were worried that the story had completely changed. We couldn’t support an alleged rapist, after all.

About 200 people came out to the event anyway, and marched through the streets of Old Quebec. But judging by the police presence and how many roads they’d closed, it appeared they’d anticipated 10 times as many people to have been there. Their PR campaign worked.

The police demonstrated just how easy it is to turn people’s heads around when they need to distract attention away from themselves. Never mind that Niyokwizera’s friend was not the victim of police violence, and never mind that even rapists and murderers shouldn’t be subjected to it — the police campaign freaked people out enough to convince them to stay home. But let’s remember that not even the shooter behind the 2017 attack on the Islamic Cultural Centre in Quebec City had snow kicked in his face the night of his arrest.

A few days after the protest, even more news came out that was damning for the police. On December 6, after their internal investigation, the Quebec City police said that they believed it was possible a crime had taken place, and referred the investigation to the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes (BEI), the province’s police watchdog. The BEI also opened up another investigation into an incident from July, where a man had asked a passer-by to call 9-1-1 for help because he feared he was in danger, only to end up being beaten by police, landing him in the hospital. Quebec City police failed to report this incident to the BEI, as they are obligated to do.

While it isn’t uncommon for police to employ tactics like the ones used in Niyokwizera’s case to distract from the real issues, it’s rare that we witness them doing so in such a brazen manner. When a Black man faces charges, especially of sexual violence, in an overwhelmingly white city with a nearly all-white police force, we need to be far more skeptical about what we’re being told by police. And it shouldn’t be enough to get us to ignore what is plain as day on camera.

None of this is a comment on whether or not the sexual assault happened, but we have to keep our eye on the ball: police brutality is never justified by someone’s behaviour. Yet in a moment of crisis, the police will do everything they can to change the channel from their alleged crimes, and if it feeds into racist narratives about Black men, I imagine they’d say ‘tant mieux.’