Journalism in Canada has suffered countless setbacks over the past decade.

Postmedia has tightened its grip on the industry, scooping up publications and chains, imposing its toxic ideology on them, and then stripping them for parts to pay off its owners. The industry has shrunk significantly, with news outlets across the country cutting staff, reducing publishing volume, moving online and, at the end of the road, shutting down entirely. Most remaining publications, ranging from major corporate outlets to independent alternatives, rely in part on money from the government and/or funding from Big Tech corporations.

The problems unfortunately aren’t limited to the business side. Since late-2016, journalism in Canada has been obsessed with the threat that disinformation from foreign actors allegedly poses. And yet, this shift has little to do with any changes in the real world, is disconnected from what readers care about, and serves journalists more than their audiences, all the while tapping into decades of anti-communist propaganda and Cold War rhetoric, holding Canada’s enemies to standards never applied to the government at home or to allies.

Disinformation journalism is one of the most toxic editorial developments in the media. Here’s where it came from, the problems with it and why we need to move past it.

In November 2016, Donald Trump stunned much of the world by defeating Hillary Clinton in the United States presidential election. Many people in North America reeled in shock at the result, and desperately searched for answers as to how it came to be. Shortly after, an explanation was put forward that was convenient for anyone not willing to take a hard look at the U.S.: Russian interference. A popular allegation made against Russia was that it had used disinformation (false information deliberately spread for political purposes) to sway some Americans into voting for Trump, which ultimately allowed him to prevail. As a result, disinformation (what it is, what impact it has had, who is behind it, how to spot it, how it can be fought, etc.) emerged as a buzzword and focus of media and politicians alike.

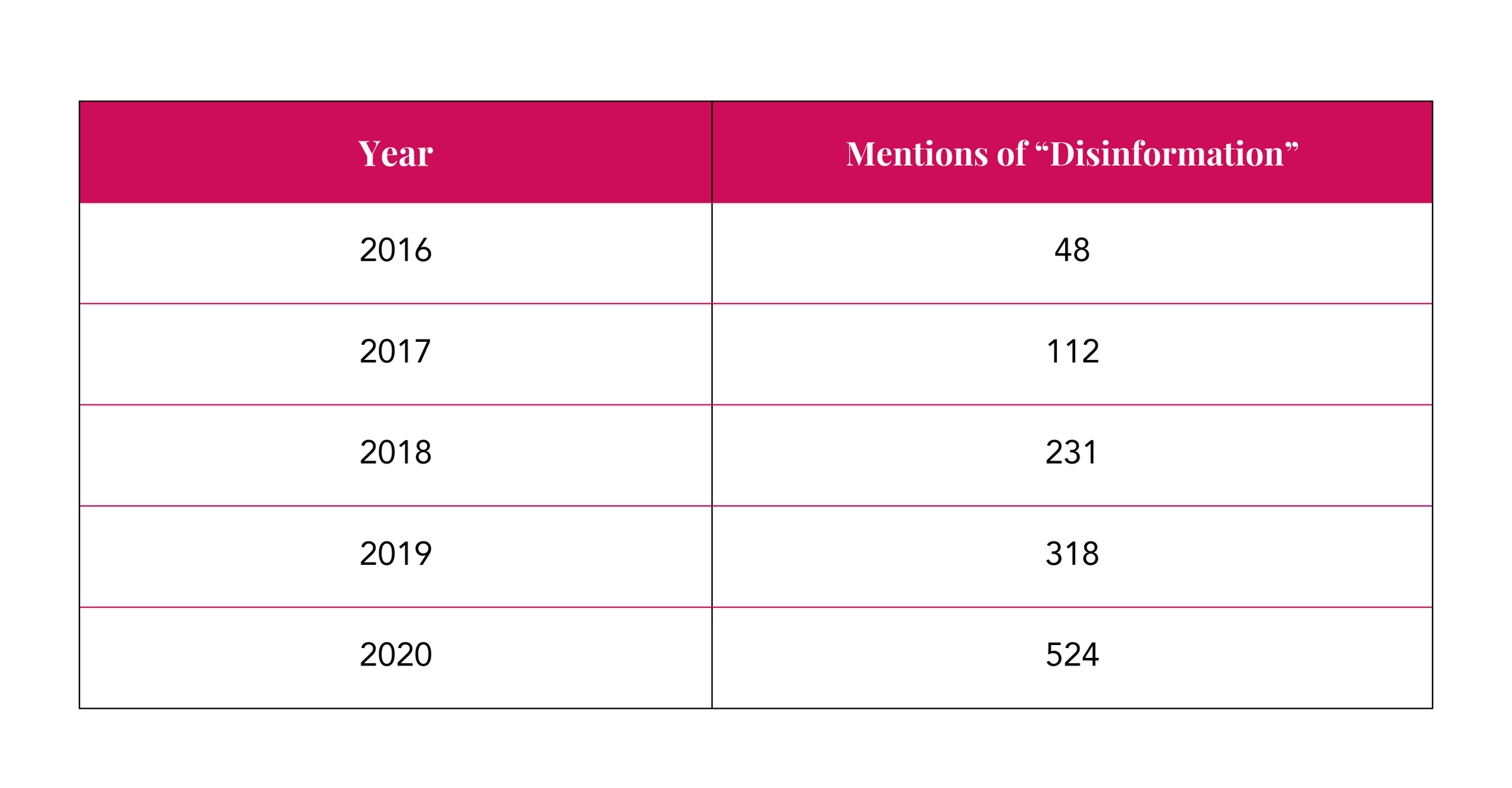

Take The New York Times: from 2008 to 2015, the word “disinformation” was mentioned an average of 21 times per year in the paper’s print edition. Once the claim of Russian interference began circulating, use of the word “disinformation” at the paper quickly multiplied.

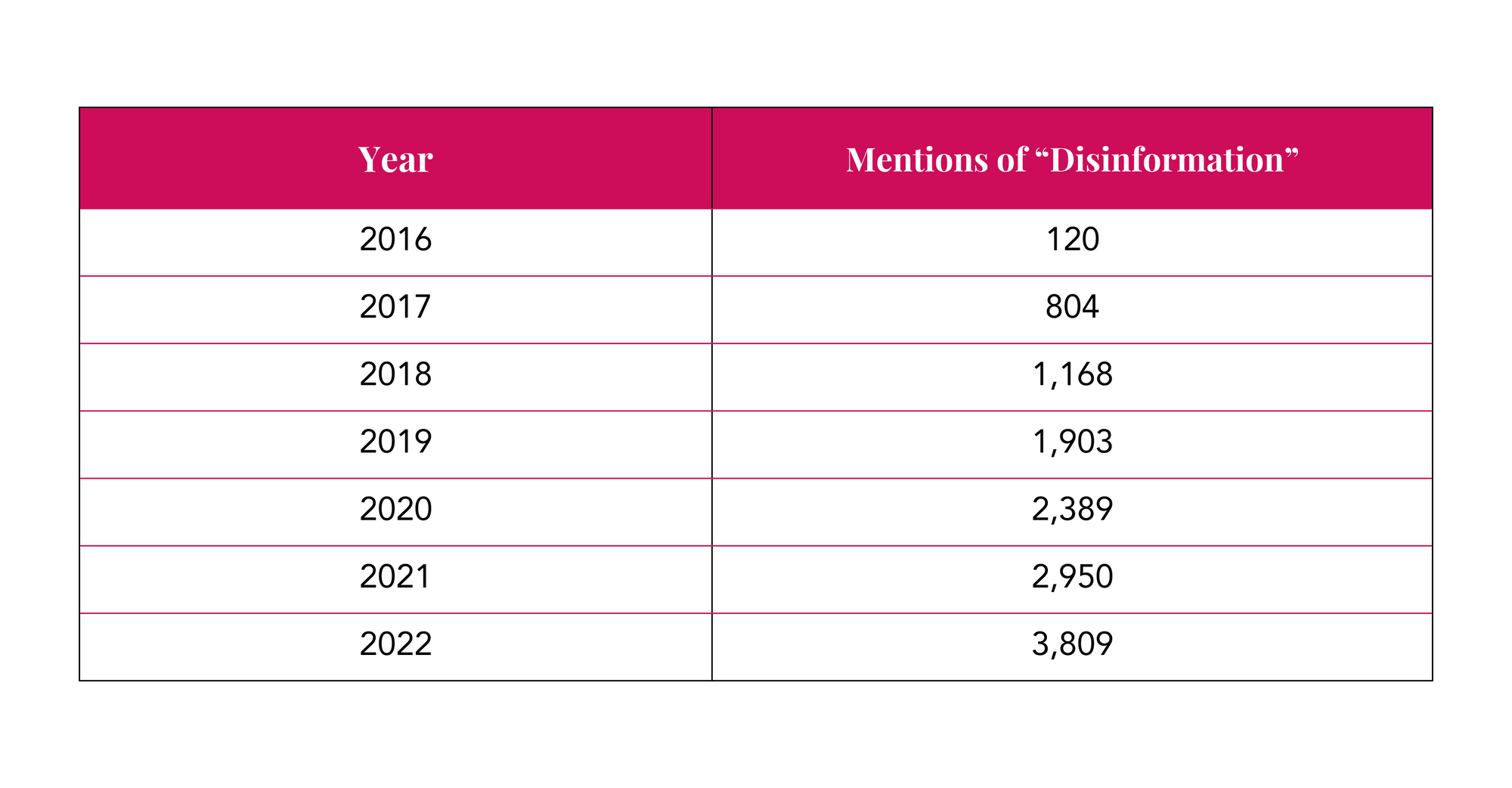

And like so much else of what’s discussed in the U.S., the conversation was picked up in Canada as well. Mentions of “disinformation” in the Canadian Newsstream database skyrocketed from 2016 onward. Taken together, there were about 13,000 mentions of the word “disinformation” in Canadian newspapers in this seven-year period. This was significantly more than the 2000s (2,323), 1990s (1,894) and 1980s (813).

The issue goes beyond mere media mentions, however, and is apparent in journalistic organizations in Canada. For example, Canada’s major journalist advocacy group, the Canadian Association of Journalists, launched a “misinformation training program” in early 2022 with the intent of providing “training for post-secondary students in every province and territory on disinformation and misinformation.” It held 13 sessions in 2022 alone, featuring some senior journalists as instructors. Journalism For Human Rights has launched several disinformation-themed programs. In 2019, the “Fighting Disinformation through Strengthened Media and Citizen Preparedness in Canada” project was launched to “train both working journalists and the general public in strategies to recognize, track and expose disinformation campaigns on social media.” They boasted that they planned to work with 300 journalists for the project. These efforts were continued with the “Combating Misinformation Project” (2020) and the Misinformation Project (2021). Toronto Metropolitan University and Carleton University, two major journalism schools in Canada, also hopped on the trend. Other schools joined in as well.

Russia And The Soviet Union

It’s not a coincidence that the obsession in Canadian journalism with disinformation began in response to an alleged action from the Russians.

The word “disinformation” is often attributed as having come from a Russian word, dezinformatsiya, supposedly coined to describe a new form of propaganda. Accounts on when it first appeared and from whom vary, with some pointing the blame at Joseph Stalin after the Second World War and others looking further back to the early 1920s. The Washington Post writes that in the Western world, the term “came into use in the early 1960s, and came into widespread use in the 1980s.” The earliest mention of the term I could find in Canadian media was in 1969, and over the next couple of decades it mostly appeared in articles about intelligence agencies, either to describe something they had done or accused a foreign adversary of doing. As such, the concept is a carryover from the past century, when Western governments accused the Soviet Union of being the creator of disinformation and oftentimes the sole practitioner of the practice (though then and now it’s more accurate to view it as a tactic used by all sorts of governments).

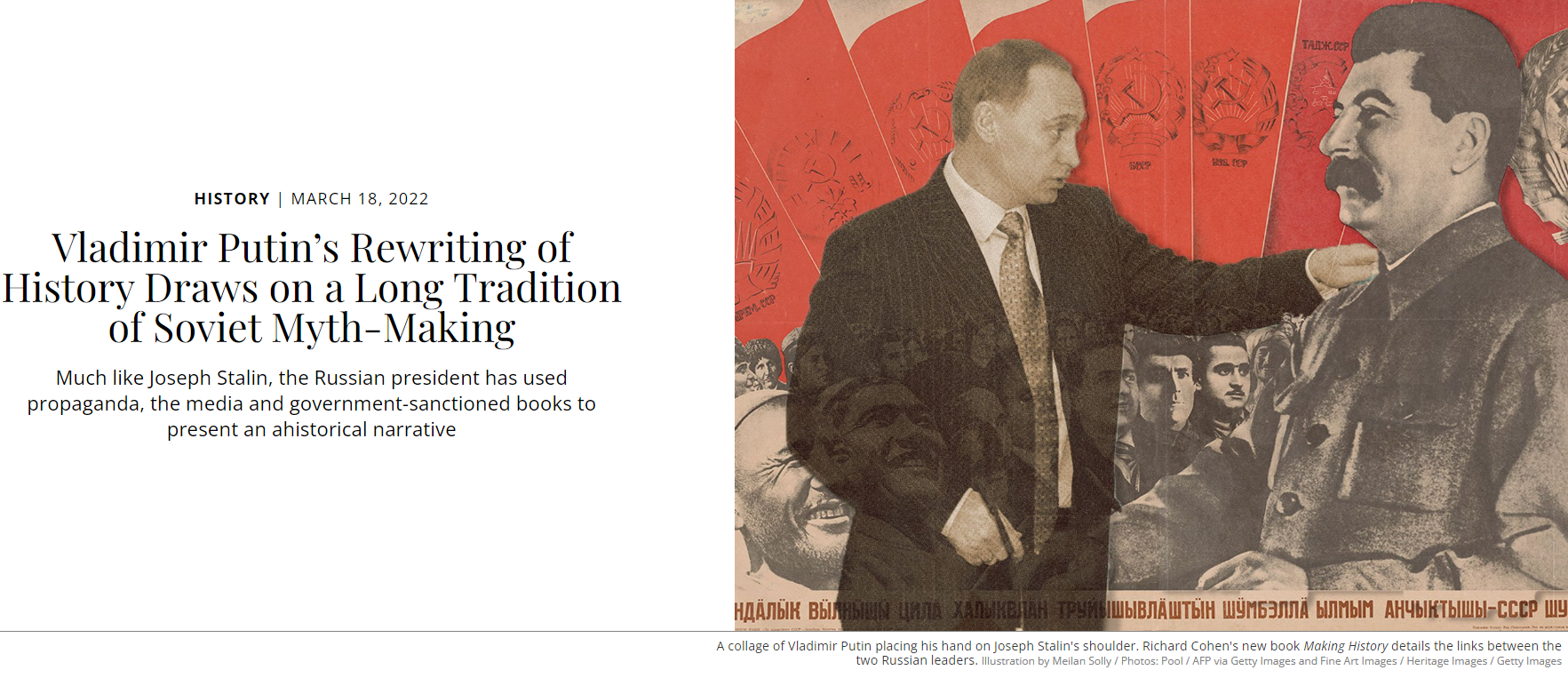

Today’s Russia — the Russian Federation — of course, is not the Soviet Union. But the media has maintained a habit of equating the two, so it’s no surprise that modern disinformation reporting portrays Russian disinformation as a return to the past or a sign of a failure to ever abandon a supposed intrinsic characteristic of the Soviet era. This is highlighted by early reporting on alleged Russian disinformation, where readers needed to be reminded of the Cold War era framing.

A Jan. 11, 2017, article from The Globe and Mail, for example, was titled, “Russian ‘dezinformatsiya' throws U.S. politics into chaos.” A March 9, 2017, editorial from the Toronto Star, meanwhile, claimed that concerns about then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland’s affinity for right-wing forms of Ukrainian nationalism were “the type of misleading dezinformatsiya (disinformation) that Russian sources have trafficked in for years, during and after the Soviet era.” Reporting since then, in Canada and abroad, has also routinely equated Russia with the Soviet Union, including through its use of manipulated imagery, with examples (included as screenshots below) seen in The Globe and Mail (Aug. 23, 2019), Smithsonian Magazine (March 18, 2022), Washington Post (May 9, 2022) and ABC (May 23, 2022).

This linking of the Russian Federation and the Soviet Union, and disinformation with the Soviet Union, was ostensibly done to offer context to readers in order to give them a better understanding of the issue at hand. In reality — whether intentional on the part of the journalists or not — it instead had the effect of both misrepresenting who practices disinformation (the earliest Canadian reporting on it from the 1970s actually focused on CIA activities) and tapping into existing anti-communist and Cold War sentiment for propaganda purposes. With this in mind, it’s no surprise that disinformation journalism ended up looking the way it has.

At Home

As mentioned above, the recent disinformation craze largely started with Trump’s electoral victory. The ensuing desire to determine how Trump had won and what could be done about the further-rightward shift of American politics was commendable, and some valuable work on this front was published. As a whole, however, the main takeaway was that a foreign adversary was to blame for an American problem. This explanation was convenient because it allowed those in the establishment to ignore their own culpability, and the serious problems within the Democratic Party.

This approach has since continued, including in Canada. Take, for example, the so-called Freedom Convoy. The event, in which thousands of people travelled to Ottawa in the winter of 2022 ostensibly to protest vaccine mandates and restrictions, got a great deal of coverage in Canadian media, including from well known disinformation reporters. Canada’s National Observer (CNO), for example, published a three-part series in February claiming that Russia was responsible for “whip[ping] up support for the ‘Freedom Convoy’ and undermin[ing] the Trudeau government.” This angle was also explored at Global News and the CBC. This same sort of framing was applied to the issue of vaccines in general, including at the Toronto Star and National Post.

The articles from CNO and Global don’t investigate what led to the creation and success of the Freedom Convoy. In fact, they seem uninterested in this question entirely. Instead, they focused on Russia’s supposed role in either instigating the Convoy or creating support for it. Their evidence? RT, Russia’s state media outlet, covered the convoy more than other outlets the reporters, or the researchers they spoke with, examined, and this supposedly means the Russian government was trying to “destabilize western democracies.”

One of the articles from CNO, which uncritically cited the U.S. Department of State twice, portrayed Convoy participants as unwitting victims of Russian activity. A CBC reporter, meanwhile, took it even further in an interview with a government official, stating: “There is concern that Russian actors could be continuing to fuel things as this protest grows, or perhaps even instigating it from the outside.” It’s difficult to imagine these disinformation reporters ever accusing the CBC’s extensive coverage of protests and riots in Hong Kong and Iran as examples of the Canadian state trying to destabilize those places or even actually being responsible for the protests in the first place.

This sort of coverage is a standard example of disinformation journalism when it comes to domestic issues. It looks at a problem, blames its existence or spread on an outside actor, often with accusations that would never be wielded against the establishment at home, and avoids examining the real, more difficult and complicated, factors at hand. It both misrepresents the problem and hampers the process of finding an actual solution.

Double Standards

Then there’s the matter of how this journalism handles international issues.

As noted, the narrative offered is that “disinformation” is a Soviet invention, practiced almost exclusively by that country and its allies, which now lives on in Russia. This narrative leaves out all or most of the examples of Western governments and intelligence agencies, and their allies, engaging in this sort of behaviour, as well as the disastrous impacts that doing so has had.

Worse, when it’s not ignoring these examples, it sometimes actually goes out of its way to make excuses for them or to portray them as somehow more noble, necessary or enlightened than when Canada’s enemies supposedly do it. This has become especially apparent since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. After years of concerns about Russian disinformation, false propaganda stories originating from Ukraine were spread gleefully and widely by Western media, with little if any follow up corrections or retractions.

Take, for instance, Jane Lytvynenko, a researcher who has been involved in the modern disinformation industry since the beginning, with a profile that expanded following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Lytvynenko’s experience in the industry has included being a senior reporter at BuzzFeed News that “focused on dis/misinformation” and a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center’s Tech and Social Change project, where she focused on “developing training on investigating disinformation.” Her website adds, “I’ve lectured at the University of Toronto, New York University, Harvard University, and others. I’ve appeared on television across the globe speaking to the issue of disinformation, from France, to Macedonia, to the US’s CNN, to my first home in Ukraine and my second home in Canada. I’ve also helped educate Canada’s teachers and students about the issue of disinformation through the Civix program.”

In a March 2022 interview with Tech Policy Press, Lytvynenko was asked about Ukraine’s baseless propaganda (which the interviewer described as the spreading of “positive energy”), and if it was in tension with the disinformation journalism that she’d helped pioneer.

Lytvynenko replied: “I mean these myths, legends and in many cases, real stories of bravery are crucial during a war. They’re not just crucial now, if I can get a little bit nerdy. These are long Ukrainian traditions of supporting those who fight for Ukrainian freedom because of course, the fight for Ukrainian freedom has been going on for hundreds of years. As a part of that legend-making, myth-making and also support for key historical figures is part of a long tradition.

In the online information environment that is at odds sometimes with the sheer, ‘Only the facts, ma’am.’ approach about the war, but I do think that it has a very important role to play. The important role is first of all, keeping up the morale of Ukrainian people. I think we’re all doing a great job at that ourselves, but we need some memes, we need some memes to share. We need to put Ghost of Kyiv on a T-shirt, even if every Ukrainian knows that it’s a myth, right. Every Ukrainian knows that Ghost of Kyiv is not one dude who’s sitting there in his airplane taking out Russians by the hundreds, right.

What it really is it’s like white propaganda. I think it occupies this really interesting space. A space that helps outline the character of Ukrainian people, even though it doesn’t always contribute to the facts as we understand them on the ground and outlining the character of the Ukrainian people is actually a kind of education because before the war, Ukrainians were not presented in a good light in most cultures.”

This is a stunning quote, indicating a seemingly complete abandonment of the supposed principles of a form of journalism Lytvynenko championed, simply because the cause the disinformation was in service of was one she supported. Later on in the interview she would warn that while “Ukrainians are wielding this power of myth-making with good intentions,” there is a “need to be careful with it.” In other words, every excuse possible, including strange appeals to ethnonationalist essentialism, was made to justify what was clearly false propaganda deployed in the most dangerous sort of context.

Later that month, Lytvynenko’s boss at the time, Joan Donovan, the director of Harvard’s research project on “disinformation campaigns,” retweeted a GIF from the “Ukrainian Memes Forces” Twitter account of a man at a computer reacting in joy, with the caption: “When a Russian streamer gets a $1 donation (he’s now the richest person in his country).” As I wrote at the time, Donovan had shared a meme that “mock[ed] average Russians suffering under sanctions imposed due to decisions out of their control.”

These two examples, from prominent figures in the industry, shed a lot of light on the disinformation field as a whole. The goal has never been to see supposed disinformation in and of itself as something to be countered, but rather something to be opposed based on who the disseminator is, and in the service of broader geopolitical aims — aims that just so happen to line up with what Western governments also support.

Government Support

Disinformation reporters often see themselves as holding the powerful to account in a battle for truth and democracy. They certainly aren’t the only journalists with grandiose visions of the work they do that are largely out of touch with reality. However, in their case, their governments are happy to support them and the work they do in many ways, including politically, ideologically, and often materially, sometimes even explicitly identifying them as partners in their geopolitical aims.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2022 statement on World Press Freedom Day is a telling example. Trudeau states, “In the age of disinformation and misinformation, independent, fact-based reporting is vital. We must all come together to support the work of journalists and double down in the fight against disinformation.” Trudeau explicitly identifies journalists as partners in the government’s campaign to combat disinformation, focusing exclusively on this aspect of the industry as opposed to any of the far more important ones. He also mentions Russia as a specific enemy to combat. This is by no means a unique statement, instead being an accurate summation of much of his praise of journalists. His identification of journalists as partners is also not unilateral, with, for example, Journalism For Human Rights identifying a 2019 disinformation project of theirs as a “response to the Government of Canada’s plan to safeguard our democratic processes from threats of interference.”

Trudeau’s statement identifies two government programs in particular as “addressing the challenges and the spread of disinformation online”: the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) and the Digital Citizen Initiative (DCI). In June 2018, the G7 launched the RRM, which Canada, president of the group at the time, describes as “an initiative to strengthen coordination across the G7 in identifying, preventing and responding to threats to G7 democracies.” The government announced that the RRM’s coordination unit would work closely with federal departments, including the Communications Security Establishment and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. Canada’s specific branch of the RRM would also monitor “the digital information environment for foreign state-sponsored disinformation,” a project which it said needed “a truly whole-of-society approach” including the work of media organizations. In his 2022 statement, Trudeau noted that the government was “providing $13.4 million over five years to bolster the [RRM],” with the 2022 budget framing it as part of an effort “to push back against the forces that challenge the rules-based international order,” namely Russia.

The DCI, meanwhile, is “a multi-component strategy that aims to support democracy and social inclusion in Canada by building citizen resilience against online disinformation and building partnerships to support a healthy information ecosystem.” The government notes that in 2019-2020 “as part of Canada’s approach to protecting its democracy, Canadian Heritage contributed $7 million over 9 months to 23 projects delivered by Canadian civil society stakeholders that strengthened citizens’ critical thinking about online disinformation, their ability to be more resilient against online disinformation, as well as their ability to get involved in democratic processes.” These projects included funding to several media organizations for disinformation efforts, such as the Canadian News Media Association ($484,300), Journalists for Human Rights ($250,691), Magazines Canada ($63,000) and New Canadian Media ($66,517).

The DCI, through a $2.5 million funding agreement over the course of four years, also aided the Public Policy Forum (PPF)’s Digital Democracy Project, which was “a multi-year project to analyze and respond to the increasing amounts of disinformation and hate in the digital public sphere.” The PPF notes that in May 2019, they hosted a media workshop on disinformation that “brought together approx. 75 participants, including 50 Canadian journalists representing traditional and digital newsrooms from across Canada.” They add, “Journalists were introduced to the scale of the disinformation challenge, the impact it has had on previous elections (incl. in Brazil and Europe), and global best practices. Following the workshop, PPF established and coordinated a network of journalists with which to communicate the findings from phase two.”

Additionally, the 2022 federal budget included providing “$10 million over five years, starting in 2022-23, with $2 million ongoing for the Privy Council Office to coordinate, develop, and implement government-wide measures designed to combat disinformation and protect our democracy.” Also that year, the government announced “the launch of a special, targeted call for proposals totalling $2.5 million to fund initiatives that help people identify misinformation and disinformation online,” elsewhere specifically naming Russia.

The examples go on, and make it clear that both government and media treat disinformation with a similar level of importance, frame it in a similar way, and to some extent see each other as partners in a similar fight (with the government willing to put up money as proof). This is an abandonment of what journalists should be doing. So why are they doing it?

Why Journalists Love It

Part of the popularity of disinformation journalism for journalists themselves, newsrooms as a whole and media organizations, comes as a result of material need. As outlined at the beginning of this piece, most news outlets rely to some extent on financial aid from the government for existence in a variety of forms, including tax credits and being designated as “qualified Canadian journalism organizations.” Simultaneously, the government has expressed an interest in supporting journalism that supposedly fights disinformation, and has dedicated an incredible sum of money to journalism in general, amounting to more than $700 million since 2018 for a variety of publications. As such, there’s a vested interest in tailoring journalism to meet what the government is looking for, particularly if jobs, newsrooms and entire companies depend upon it.

Looking beyond the business case, disinformation journalism is attractive to journalists partly because it offers a sense of purpose. Legacy media no longer has a near-exclusive hold on readers, and it’s easier than ever to find a variety of news sources with varying perspectives and approaches. Instead of seeing this as a net positive, disinformation reporting allows journalists to point to it as a problem and hold themselves up as a solution. Their job is no longer to write about what’s going on, but to filter out what they deem to be illegitimate for readers. This has the function of reinforcing the role of legacy media, finding a purpose in the industry (the only “legitimate” source of information you can trust happens to be the sorts of places they work at) and trying to repair relations with readers.

The approach, however, has been a failure. As mentioned at the beginning of this piece, journalism in Canada has been hitting new lows in recent years with regard to its financial state. Things are also looking bad in terms of its perception among Canadians. A 2022 report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that trust in Canadian media from readers had dropped to its lowest point since 2016 (around when the disinformation craze started). At the time, about 55 per cent of respondents said they “trust most news, most of the time.” In 2022, just 42 per cent of respondents said the same.

Interestingly, an article from The Conversation about this report claimed it was especially important due to governments becoming “increasingly active in regulating digital media ecosystems and supporting local journalism to protect democracies from disinformation and misinformation” and the “Russian invasion of Ukraine [and the resulting] rampant misinformation.” The article adds: “During this time of disruption and transformation, surveys like the Digital News Report contribute to our understanding of the relevance and legitimacy of professional news sources from the public’s point of view.”

The Conversation article portrays the decline in trust readers have in the media as being a result of more dis/misinformation in news outlets that readers are identifying and responding to. Another explanation is that the media’s obsession with dis/misinformation is actually playing a role in alienating readers. Part of that is due to the patronizing attitude that has come with disinformation journalism — including that it has increasingly focused on smearing dissenting opinions rather than exposing empirical falsehoods — and a misidentification of how reporters can serve readers. This doesn’t mean there’s no value in legacy media, or that journalists don’t have anything to offer to any readers. It does mean that investing in disinformation journalism has been a mistake.

Finally, there are the true believers, who genuinely perceive the problems at home as coming from abroad, who see these issues as arising due to the spread of lies or inaccurate information and who think that merely debunking or getting to the root of these campaigns will be of great benefit to society at large. They take their interest in disinformation as a marker of its importance, and their focus on it as an inherent sign of reader interest. They propagate a liberal understanding of the world and how things work, deployed in service of Western foreign policy objectives. For them, disinformation journalism is a natural fit.

Disserving Readers

Regardless of their motivation for producing disinformation journalism, journalists and newsrooms as a whole are doing a disservice to readers.

In January, in response to a company laying off journalists, the Canadian Association of Journalists tweeted, “We are disappointed to hear that Overstory has laid off its staff at the Capital Daily. Local news and journalism play an important part in keeping communities informed amidst a disinformation crisis.”

Local journalism is, at its best, valuable for so many reasons. The fact that CAJ failed to list any of them, instead focusing on the fad of disinformation reporting, is a sign of a broader shift away from the sort of journalism that matters to people.

Does supposed Russian disinformation hurt people in their day to day lives? Is that what they go to sleep at night worried about? When they get evicted from their homes or stop dreaming of ever owning one, is it because of disinformation? When their friends die from drug poisoning, was it disinformation that killed them? Is disinformation responsible for the abysmal public transportation they rely on to get to jobs where they are underpaid and working for people and places that can dodge getting taxed with impunity? When they’re sick and go to an emergency room, is disinformation responsible for the astonishing wait times they have to suffer through, if the emergency room is even open in the first place? When they can’t find a family doctor, is it because disinformation consumed all of them?

The examples go on. Disinformation has a negligible impact on the lives of the vast majority of people, and by focusing efforts on it, journalists are missing out on tackling the issues and stories that do matter. Focusing on these issues could help lead to real public change, rebuild trust with readers and actually get to the root of the social issues that make supposed disinformation so attractive to some people. Instead, they fixate on a hobby horse, and at the same time regurgitate old Cold War tropes for a modern era, working in line with the government in a period where it supports a war bringing us closer to nuclear catastrophe than at any point in decades.

If journalism in Canada is to survive in a manner that’s of interest and service to the general public, the disinformation racket has to be shut down.