Hi Passage readers! Welcome to your course on the welfare state.

I’m Adam King, and if you subscribe to Passage’s Class Struggle newsletter you’ll have heard from me before.

I’m currently a post-doctoral visitor in the Department of Politics at York University in Toronto. Generally, I research and write in the areas of work and labour studies, and Canadian political economy. I’ve spent the past several years writing about work in the mining industry, labour laws and standards as well as public policy.

As a democratic socialist, I also spend a good portion of my time thinking and writing about the welfare state.

This course will serve as a primer on the welfare state, and its history, politics and potential. I hope the course will help you think critically about the welfare state, social democracy and capitalism. Understanding the victories and limitations of social reform under capitalism is integral to imagining a socialist politics that, hopefully, moves us beyond capitalism.

In this first lesson, we’ll explore what the welfare state does or should do. In the next three lessons in the course, we’ll look at: the current composition of Canada’s welfare state and the challenges posed by neoliberalism; ways to fix and improve on what remains of Canada’s welfare state; how we might expand the welfare state and pursue reforms that move us in the direction of democratic socialism.

But before doing all of that, I want to take you on a brief historical detour that will help you understand where the welfare state originated, and what its relationship to capitalism has been since then.

In doing so, you’ll also get a better understanding of “social democracy.” It was, after all, mostly parties of the social democratic variety throughout Western Europe and North America who either implemented — or pressured bourgeois parties to implement — social welfare policies and programs.

Let’s begin!

The History Of The Welfare State

Social democracy is and was a unique form of working-class, democratic politics.

Western political parties of the left — whether officially social democratic, socialist or labourist — and their affiliated trade unions were instrumental in achieving mass democracy and universal enfranchisement in many European countries. (In North America, working-class political formations were founded after white, male suffrage was already widespread — in fact, some people argue that this is one reason why working-class parties are weaker here.)

Generally, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, workers could vote and had formed their own political parties in most of the capitalist democracies in the West — though discriminatory exclusions of women, racialized people and immigrants remained in many contexts.

With the electoral arena more open, working class parties found the revolutionary path to power, of which the Bolshevik Revolution is the primary example, off the table. (Although, as the Cold War intensified, fear that workers would demand something approximating “socialism” further pressured Western governments to extend social reform). Consequently, when Western working-class parties formed governments, they were without any electoral mandate to “abolish capitalism.” Instead, socialists with governmental power had to develop a policy program in the context of democracy and capitalism.

Broadly, this package of reforms, including things like unemployment and public health insurance, social housing, and public pensions, is what we now refer to as “social democracy.”

As the political scientist Adam Przeworski argues, European socialist and social democratic parties faced an immediate dilemma once elected to office: they had no explicitly “socialist” economic program. Rather, social democratic governments were in the contradictory position of having to “manage” capitalist economies, while trying to institute a policy program that would satisfy their working-class electoral base.

Social democrats needed to increase government spending on things that workers wanted — such as healthcare, education and other cash benefits — but were also compelled to ensure that businesses remained profitable.

Social democratic governments recognized that capitalists hold the ultimate trump card: the “capital strike.” Tax them too much, spend too freely, give workers too much power and the rich will refuse to invest, tank the economy, drive unemployment up, and, usually, cause enough disruption that even a well-organized working-class electoral base will turn on a socialist government.

So, from the early 20th century, social democratic parties throughout Western Europe set about attempting to “smooth the rough edges” of capitalism. In some countries, particularly in the Nordics, parties of the left, backed by the power of trade unions, passed legislation designed to raise workers’ living standards and make existence under capitalism less precarious and more economically stable.

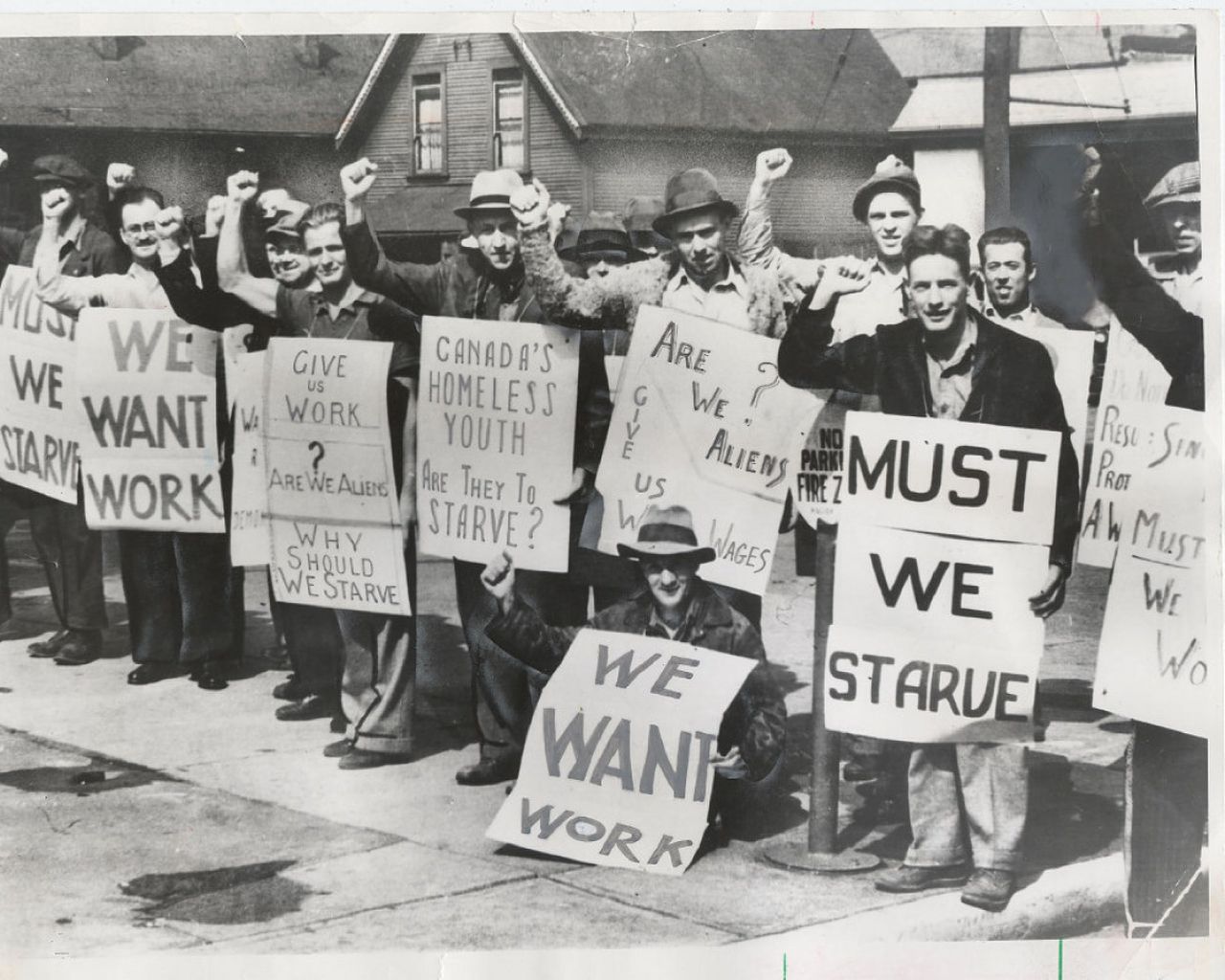

Where they couldn’t form national governments — as, for example, with the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the precursor to the New Democratic Party, in Canada — left parties formed subnational ones in provinces or cities, or built sufficient power to pressure parties to their right to pass national social welfare policies.

Left parties in power also benefited from the emerging Keynesian policy consensus during the period spanning from the Great Depression to the Second World War. The economist John Maynard Keynes’ ideas provided social democratic governments with a set of macroeconomic tools and a ready-made justification for large increases in government spending.

For example, the introduction of unemployment insurance programs conformed to both Keynesian and socialist objectives: When an economic recession occurred and an increasing number of workers found themselves out of jobs, unemployment insurance checks served as an “automatic stabilizer,” providing workers with needed income and ensuring continued demand for business output.

In the 30 or so years following the Second World War, the mix of social democratic governance, Keynesian economics and strong trade unions produced a period of unparalleled economic success as growth levels soared, public spending expanded, workers’ living standards rose and inequality remained comparatively low.

Social democracy, however, confronted mounting contradictions beginning in about the mid-1970s. As the economist historian Aaron Benanav’s research shows, declining manufacturing output and slow productivity growth produced economic stagnation and profitability crises throughout the West by the mid-to-late 20th century.

This set the stage for a political pushback from the right, which ultimately culminated in the triumph of neoliberalism — but more on this in the next lesson.

Conceptualizing the Welfare State

Now that we’ve reviewed some of the welfare state’s history, let’s go over what exactly the welfare state is and does.

Broadly, we can think of the welfare state as including two main functions: non-market public services and income transfer programs.

In the first category, there is public healthcare, education, fire and other emergency services, public transportation, and utilities.

How public services are delivered in Canada varies. Federal, provincial and municipal governments all share in the cost and delivery of services — we’ll discuss this more in the next lesson. Governments draw on numerous tax revenue streams to fund these services, particularly those that operate with no “user fees,” such as healthcare.

In some cases, public services are performed by state-owned enterprises — in Canada, usually called “Crown corporations” — that also operate to produce a surplus. For example, Canada Post ensures that inexpensive mail services are available across the country by having profitable routes — like in downtown Toronto — subsidize unprofitable services, such as sending a letter to Whitehorse.

In all cases, public services operate outside of “market principles.” This means that even when they require users to pay some portion of the cost at the point of use — for example, fares on public transportation — that price isn’t determined by supply and demand but rather reflects a mix of public funding and user fees.

As a result, how the “costs” of public services are distributed is an inherently political battle. Socialists fight to increase the tax-based funding of services to shift more of the burden onto the wealthy. User fees, by contrast, hit everyone “equally,” irrespective of their ability to pay.

In the second category, income transfer programs, we have things like unemployment insurance, maternity and parental benefits, social assistance and disability support programs, child benefits, and public pensions.

Although these numerous programs are aimed at different subsets of the population — the unemployed, people with disabilities, children and the elderly — they address the same issue in different ways: at all times, huge portions of the population are not engaged in paid work. This is temporary for some of these people (the unemployed, new parents and children), while others will remain outside of the labour market permanently (those with certain disabilities and retired people).

Along with providing people with non-labour income, sometimes public policy attempts to aid re-entry into the labour market, such as with unemployment insurance. In other instances, a robust welfare state secures adequate incomes for those who can’t participate in paid work, such as with disability payments.

Because capitalism only values work performed for wages, the overarching goal of welfare state income transfers is to redistribute money from workers and non-workers to correct for this inhumane feature of our economic system.

A robust welfare state that redirects income through various transfer programs can make life outside of the labour market less socially harmful, in addition to making the transitions in and out of paid work throughout a person’s life cycle not as stark and risky.

Different Types Of Welfare States

Some liberal thinkers argue that spending on the social welfare state tends to grow as a consequence of countries becoming richer, and opting to devote a greater portion of their gross domestic product to public services and social insurance.

There’s a certain truth to this argument. However, the liberal conception of “social democratic capitalism” fails to account for the class struggles that shape the welfare state and, consequently, to distinguish between different types of welfare states.

The sociologist Gøsta Esping-Andersen, in his classic, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, outlines three different sorts of welfare states: liberal, corporatist and social democratic. Each is the result of particular class struggles and each continues to shape politics differently.

These three welfare state types are primarily distinguished by the degree to which they “decommodify” labour. In other words, welfare states are defined by how much they reduce peoples’ overall dependence on paid work and “the cash nexus.” Every additional income supplement or public service reduces a worker’s dependence on paid work. As Esping-Andersen puts it, “decommodification occurs when a service is rendered as a matter of right, and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market.”

Liberal welfare states, such as in Canada and the United States, are defined by “means-tested” targeting of services to the poorest people, modest income transfers and overall stinginess. For example, the pandemic highlighted the inadequacy of Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) system. Before the pandemic, only 42 per cent of unemployed workers qualified for EI because of the program’s strict eligibility criteria. Others were poorly protected due to EI’s relatively low income replacement levels.

Corporatist welfare states, like those of Germany and France, have stronger public benefits, but restrict who has access along various status hierarchies, such as employment status and gender. Germany, for example, is infamous for a highly bifurcated labour market wherein workers with jobs in core industries enjoy relatively extensive welfare state benefits while those in “peripheral” sectors are largely denied comparable protections.

The social democratic welfare states of the Nordic countries are the most “decommodified,” emphasizing universality, generous public services and income supports, and an overall policy orientation that promotes equality and solidarity. Childcare in Sweden provides an illustrative example: Swedish “Educare” operates as a universal, subsidized preschool and daycare service with fees proportional to family income (families pay no more than 3 per cent of their net income). This model ensures that all families have access to the same high-quality service, rather than rich families buying private daycare and working-class families being relegated to an underfunded public system.

These policy differences have a huge impact on class politics. In short, the politics of the welfare state shape the degree to which workers are empowered, both as individuals and as a class. Workers who are less market dependent tend to be more assertive and solidaristic, and therefore able to improve their individual and collective bargaining power.

Moreover, welfare states that promote universality through progressive taxation and extending benefits to everyone, rather than targeting benefits at the poor, tend to be more politically durable and popular. It’s much harder for right-wing politicians to attack programs from which everyone feels they benefit.

Canada’s “liberal welfare state” has long been under attack from politicians across the political spectrum. Public services, like education and healthcare, have faced deep cuts and restructuring, while income support programs remain highly targeted and quite stingy. This ends up stigmatizing the poor and reducing popular support for many social services and income support programs.

In the next lesson, we’ll explore this issue further by looking at the composition of Canada’s welfare state and considering the ways neoliberal politicians of all political parties have hollowed it out.

Thanks for reading,

Adam.