A recent strike by child and family service workers in Manitoba demonstrates how unions can strategically use arbitration — not as a substitute to going on strike but as a powerful complement.

Utilizing new provisions introduced as part of a package of labour law reforms that brought anti-scab legislation to the province, the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union (MGEU) was able to win big for workers. How they did it should serve as a lesson for other unions.

The MGEU represents roughly 500 members at the three Manitoba agencies in this case: Michif Child and Family Services, Métis Child, Family, and Community Services, and Southeast Child and Family Services.

Collective agreements covering full-time and casual employees across the agencies expired on Jan. 31, 2023, in the case of Michif CFS and Métis CFS, and March 31, 2022, at Southeast CFS. Bargaining for new collective agreements did not begin until November 2023, with the parties struggling to reach agreement on key issues related to pay.

Achieving wage parity between workers at these Indigenous organizations and other similarly situated workers employed by provincial agencies was a key union objective. Furthermore, increased provincial government funding suggested this was an achievable objective. As the union pointed out, two of the agencies would receive an increase of $2.4 million as part of the province’s new $11.4 million increase to child and family services funding.

However, by March 11 workers across the three agencies looked poised to strike as the employer failed to meet worker demands related to pay parity. “It shouldn’t matter what community in Manitoba you come from. If you are connected with child and family services, you and your family deserve the same quality of care. And if you are a worker providing care or supporting those who do, you deserve to be paid fairly for that work, regardless of which agency you work for,” MGEU president Kyle Ross said in a union press release.

With a strong strike mandate from members in hand, the union issued a two-week strike notice, beginning a countdown to a March 25 deadline.

With a strike looming, Southeast CFS presented an offer to members that achieved wage parity with provincial employees on March 24. A bargaining victory now secured with one agency, the union postponed its call to strike this employer. Winning this key demand at Southeast CFS also allowed the union to leverage its newly inked deal with the remaining two agencies.

When the strike deadline arrived, more than 100 workers at Michif and Métis organizations walked off the job. In total, more than 330 people work between the two organizations, yet only a portion of them could lawfully withdraw their labour. Because the workplaces in question provide essential child and family services, a part of the workforce had to remain on the job.

This is where things got interesting and instructive.

As part of the labour relations amendments that secured an anti-scab law in Manitoba (under Bill 37), unions also agreed to a process for determining and negotiating essential services prior to work stoppages. Under this new arrangement, unions and employers must determine if any essential services exist, and if so, negotiate what portion of the workplace needs to operate during a strike or lockout.

Some labour analysts were critical of this new essential service requirement, seeing it as a capitulation in the anti-scab fight. However, this may be overly harsh for several reasons.

First, the bar for what constitutes an essential service is very high. An employer needs to demonstrate that a withdrawal of labour poses a significant risk to life, health or the environment. Furthermore, where the parties disagree, either can apply to the Labour Board for a determination.

Second, where essential services are found, the law requires only the minimum service necessary to maintain health and safety. This effectively bars employers from abusing essential service requirements. It also means that unions have a say in who performs the essential work, allowing the union to ensure compliance with the terms of the essential service agreement.

Last, in situations where an essential service requirement substantially interferes with the union’s right or ability to strike, the union can apply for binding arbitration. Resort to arbitration is limited to select circumstances and must provide a meaningful alternative to striking that is compliant with the Charter-protected right to free collective bargaining.

After Bill 37 came into force, MGEU and the child welfare organizations negotiated essential service agreements and strike protocols in February and March 2025, respectively, in compliance with the new amendments.

According to documents MGEU provided to Class Struggle, the union agreed that at least 50 per cent of staff would remain on the job during a strike at each worksite covered by the collective agreements. Workers at the agencies provide essential care services to vulnerable clients. Under these circumstances, maintaining service can be vital, even though this can also significantly reduce the number of workers able to withdraw their labour and picket.

Employer layoffs soon complicated matters, however. Early in March, 45 MGEU members at Métis Child, Family, and Community Services and 18 members at Michif Child and Family Service were laid off. The union interpreted these layoffs as a pressure tactic.

“By announcing the layoffs at this time in the bargaining process, it’s clear that this is an aggressive bargaining tactic to try and intimidate front-line workers to accept wages lower than other CFS workers in Manitoba have received,” the MGEU said in its press release. As the union further noted, there was no talk of layoffs until strike preparations were underway.

Yet, the layoffs also had knock-on effects not only for the union’s ability to continue its strike while complying with the essential service agreements but also for its use of binding arbitration. Once the layoffs took effect, MGEU was effectively unable to maintain its picket lines because striking workers were needed to perform essential work. This then opened a path for the union to argue that there was substantial interference with its ability to strike and thus apply for arbitration.

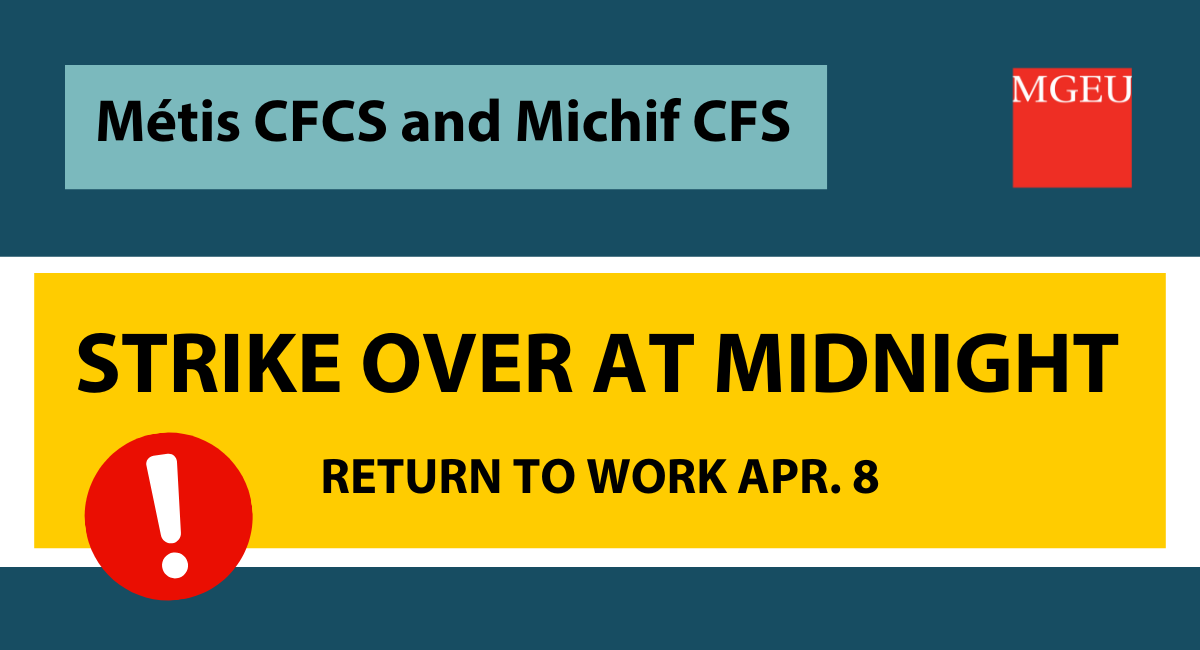

With its right to strike infringed, the union filed with the Labour Board to force arbitration on the employer. On April 7, the union announced that the employer had agreed to proceed to arbitration, thus ending the strike at midnight on April 8. “This is an important step forward in our efforts to achieve wage parity for CFS members,” Ross said in the union’s news release. “These workers should get the same pay as their counterparts in the Civil Service, and we will continue to advocate for that outcome in arbitration.”

Any agreement reached as a result of the union application for arbitration would have been limited to six months under the terms of the new labour relations amendments. This provided MGEU with additional leverage to compel the employer to voluntarily proceed to arbitration. An agreement reached through voluntary arbitration could cover a more standard length of time and thus avoid returning to the bargaining table in short order. In other words, the union was able to pressure the employer into voluntary arbitration on terms favourable to workers.

Most importantly, the union used its arbitration option where it was most strategically advantageous to do so. Having already secured a precedent-setting deal at Southeast CFS, the union remains confident that an arbitrated deal at the remaining two agencies will match the first.

This episode is a reminder for unions and labour activists not to fetishize the strike. Under most circumstances, withdrawing labour is the strongest weapon workers possess. However, we shouldn’t overlook instances where alternative courses of action can achieve more or complement limited strikes, especially when unions have adequately prepared and mobilized their members.

Of course, favourable amendments to the provincial labour relations framework set the background for MGEU’s successful strategy. Securing anti-scab legislation in Manitoba was a major victory. But as this recent case also demonstrates, the accompanying changes related to essential services and arbitration have also provided workers and unions with tools to use to their advantage.

Importantly, the effective use of arbitration requires that unions first do the hard work of mobilizing members and resources to maximize their bargaining power. Over the past three years, MGEU has undertaken a new strategic plan to increase member involvement and strike preparedness. The union has increased picket pay in order to better prepare for strikes and mobilize members to deliver strong strike mandates. This internal organizing and preparedness paid off. This bargaining round demonstrates this clearly, as did MGEU’s strikes at Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries and Manitoba Public Insurance in the summer of 2023.

With a more favourable labour law regime in place, the union was able to make gains on an important issue — wage parity — for workers at three Indigenous organizations providing essential services to vulnerable clients. Unions in Manitoba and beyond should look to this case for inspiration and guidance.

CORRECTION: This newsletter has been updated to note that MGEU increased picket pay alone, not picket pay and dues. The Maple regrets this error.

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- April 22 | A Major Canadian Union Is Calling For Pensions To Divest From Tesla

- April 14 | The Left Must Rebuild Our Electoral Power

- April 7 | Here Are Labour’s Policy Priorities For The Election

- March 31 | The Liberals And Conservatives Are Proposing Terrible Tax Cuts