How did labour fare in 2025?

In many respects, last year was a mixed bag for workers and unions in Canada. Though union wage gains were relatively healthy, the overall economy continued to cool with unemployment creeping up and many workers still feeling the cost-of-living crunch.

The United States administration’s ongoing trade war shaped Canadian labour politics for much of the year, underlining Canada’s dependence on U.S. exports and the need for an alternative economic strategy. While the worst outcome was averted in April’s federal election, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s Liberal government quickly signalled it would be no friend of workers. Under the guise of responding to the American trade threat, the Liberals pushed through troubling legislation that will fast-track fossil fuel infrastructure with scant opposition from labour.

Strike activity was down in 2025, though moments of resistance were notable, such as Air Canada flight attendants’ defiant stand against the federal government’s back-to-work order and a long strike by British Columbia public sector workers.

Unions also notched a pair of organizing breakthroughs in B.C., with workers at an Amazon warehouse joining Unifor and Uber drivers in Victoria becoming the first to unionize. At the same time, overall union density will likely remain unchanged at around 30 per cent nationwide.

These were just some of the highlights, but what do the data on work stoppages and wage settlements tell us?

Class Struggle In 2025

After inexplicably removing its work stoppage data several months ago, sparking calls for an explanation and better record-keeping practices going forward, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) restored the figures just before the end of the year. This therefore allows us to gauge how strikes and other indicators of class struggle in 2025 compared to previous years.

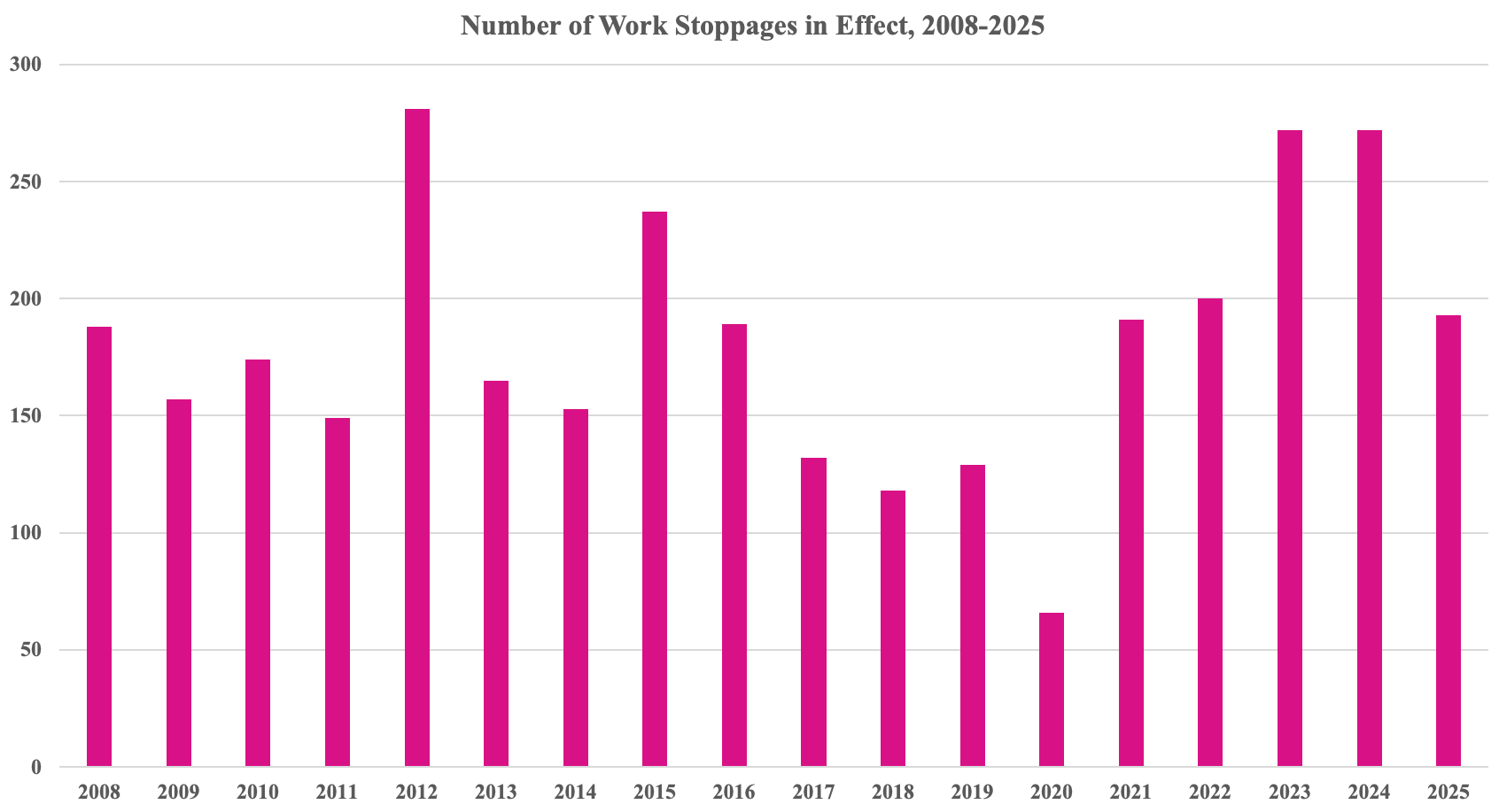

From January to the end of October, there were 193 strikes and lockouts in effect, down from 272 in both 2024 and 2023 (according to ESDC’s revised numbers). When the final two months of the year are added later, total work stoppages for all of 2025 will likely surpass 2022, but not reach the numbers seen in 2023 and 2024.

Of the 193 work stoppages in effect in the first 10 months of 2025, 103 (or 53.4 per cent) occurred in the public sector, while 90 (or 46.6 per cent) occurred in the private sector. With union membership highly concentrated in the public sector, private sector union members appear to have punched above their weight last year when it comes to overall work stoppages.

Taking a slightly longer view, the level of class struggle appears to be returning to what we might call a post-Great Recession norm, as the small wave of worker discontent following the pandemic cools.

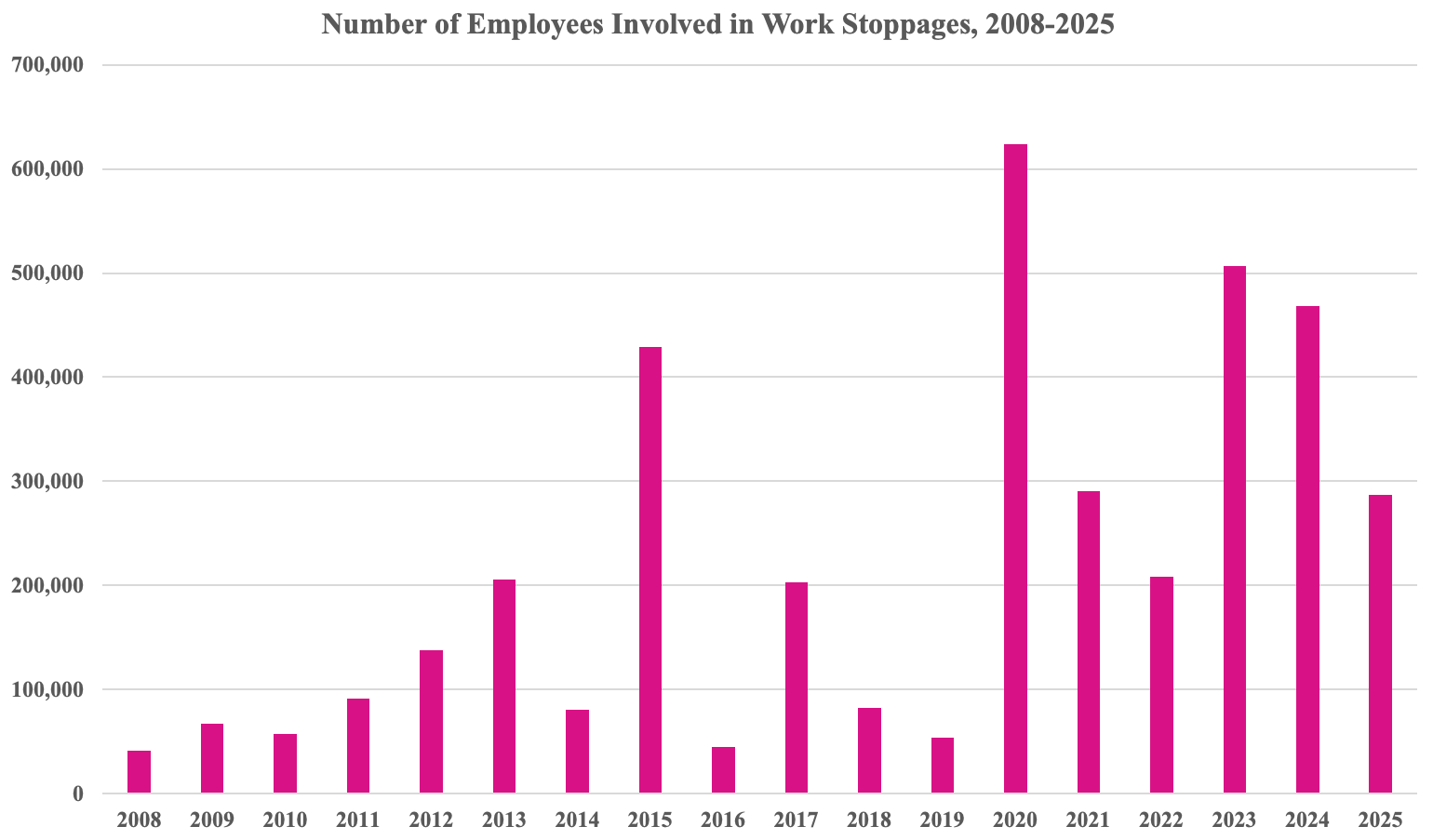

While the number of work stoppages dropped by about 30 per cent from 2024 to the first 10 months of 2025, the number of workers involved in strikes and lockouts fell by almost 40 per cent.

From January to the end of October, 286,628 workers were involved in strikes and lockouts, down from 468,740 in 2024 and 506,757 in 2023. Though 2025’s figure will rise when the final two months of the year are added later, as with work stoppages overall, the number of employees involved in work stoppages last year will likely look more like 2021 than the previous two years.

Compared to most years in the decade or so before the pandemic, however, there are still many more workers participating in strikes and lockouts now. This is largely explained by the growing militancy of public sector workers and the willingness of large, public sector bargaining units to strike.

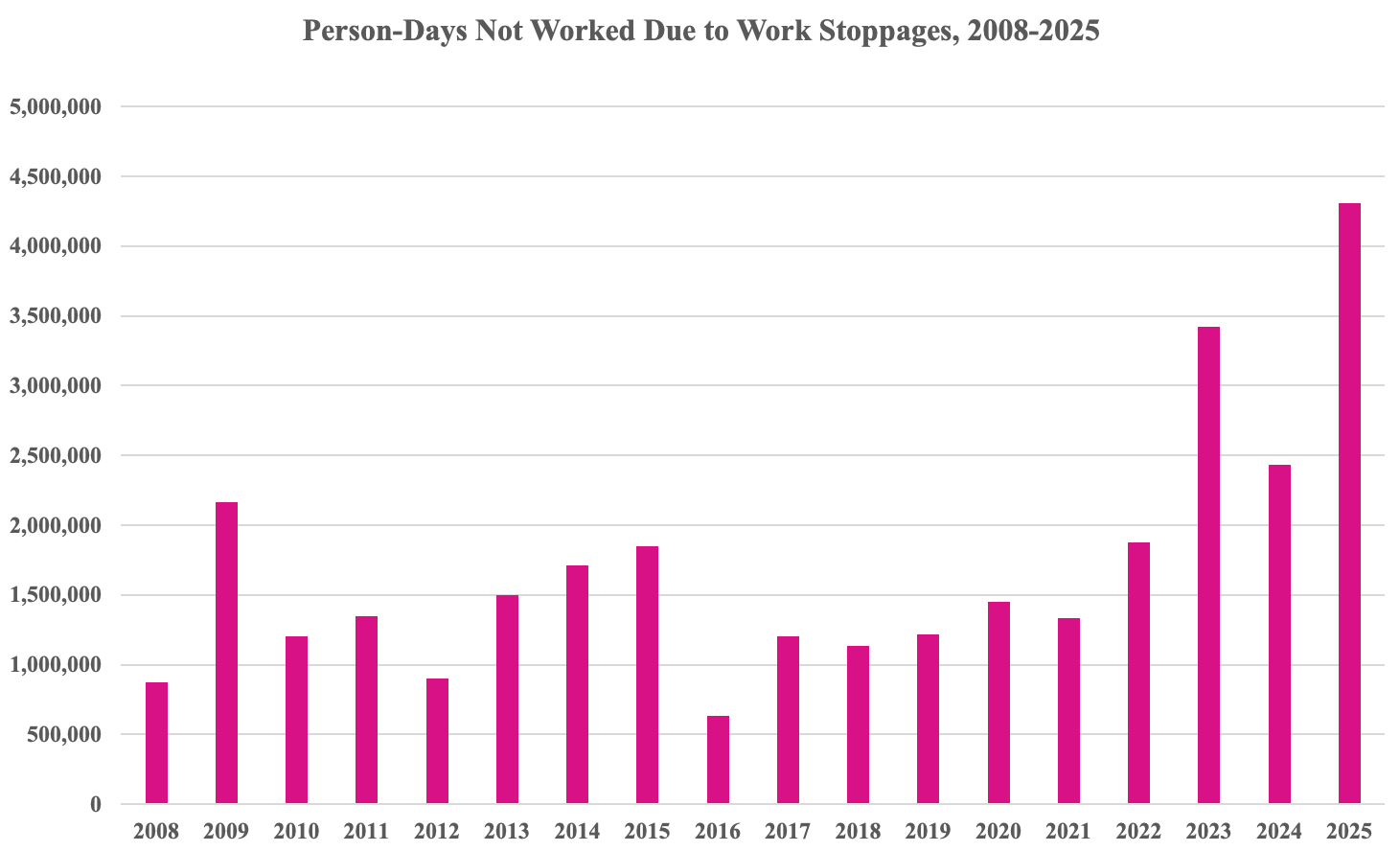

Despite the numbers of strikes and workers involved in strikes both falling, last year nevertheless saw a significant uptick in person-days lost to work stoppages.

In 2025, there were 4,307,910 person-days lost to work stoppages, up from 2,431,868 the previous year. In fact, last year saw the largest number of recorded person-days lost to strikes and lockouts since 1990 (though 2005 also came close).

This measure can be difficult to interpret. On the one hand, more person-days lost to strikes could mean workers are making defiant demands and holding out for more, but it can also indicate employers willing to wait their striking workers out.

As these three measures suggest, the overall level of class struggle in 2025 remained slightly above the decade or so before the pandemic, but seems to be on a downward trajectory from the wave of militancy witnessed post-pandemic. Interpreting recent figures against the longer history of workers’ struggles in Canada, we remain a long way from the levels of resistance witnessed in the late 1970s and early '80s.

Wage Settlements And Notable Victories

Although the cost of living continues to weigh heavily on many workers, particularly when it comes to food and housing costs, inflation has decelerated and remains at more manageable levels. At the same time, union members have been champing at the bit to renegotiate their wages and make up for losses incurred during the post-pandemic inflation.

In 2025, average annual union wage settlements by percentage of salary increase continued to climb.

Average annual wage increases reached nearly 4 per cent in major collective agreements covering 500 or more workers (100 or more in the federal jurisdiction) in the first 10 months of 2025. This was up from annual averages of 3.4 and 3.3 per cent recorded in 2024 and 2023, respectively, and well above the figures for pre-pandemic years. Unions continue to front load their contracts as well, with the average first-year wage increase in major union contracts coming in at 5.8 per cent last year, up from 4.8 per cent the previous year.

The wage gains of private sector workers outpaced those of public sector workers. Average annual wage increases for the former group reached 4.2 per cent in 2025, with average first year increases in new collective agreements hitting an impressive 7 per cent. Public sector annual increases were 3.4 per cent, unchanged from last year, with average first-year increases falling from 4.8 per cent in 2024 to 4 per cent in 2025.

It remains to be seen if unions can keep this momentum up in 2026, or if these impressive gains are temporary, the result of bargaining units making up for post-pandemic losses in one-time deals.

Notable Wins

Early in 2025, Amazon shuttered all of its Quebec facilities in response to workers unionizing a Laval warehouse in 2024. This was a crushing blow. However, Unifor’s later remedial certification in B.C. breathed new life into the fight to organize Amazon. We now wait to see if the workers can secure a first contract, and if the union can make inroads at other facilities in B.C. and across the country.

Also in B.C., Uber drivers in Victoria became the first ever to unionize when they joined the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), Local 1518. Taking full advantage of recent legislative changes that classified app-based workers as employees for the purposes of collective bargaining, UFCW engaged in a creative organizing drive and managed to secure a large bargaining unit covering the whole city of Victoria.

Perhaps the most exemplary victory of 2025 belongs to the more than 10,000 CUPE flight attendants at Air Canada who refused to comply with the federal government’s unjust back-to-work order in August. After delivering the strongest strike vote in recent Canadian history, these brave workers stood firm against the government and their employer. Then, during a circumscribed contract ratification process, flight attendants rejected Air Canada’s wage offer, sending this item to arbitration, where it presently remains.

Fight attendants did the entire labour movement a service by demonstrating that resistance to government overreach and oppression is possible.

Government And Employment Pushback

The question now remains: Will the Air Canada episode mark the end of the federal government’s love affair with section 107 of the Canada Labour Code? The government’s series of provocative actions intervening in strikes across sectors in 2024 continued into 2025, but may now have run their course. Time will tell.

The saga at Canada Post also continued throughout 2025, with the Canadian Union of Postal Workers restarting rotating strikes in May and then rejecting a forced ratification vote in July. In September, the federal government announced sweeping structural changes at the Crown Corporation, which may have hastened the tentative agreement finally reached between the parties days before the Christmas holidays.

The government of Quebec has also had its sights set on organized labour. In February, the CAQ government tabled legislation to expand essential service designations and significantly restrict the right to strike. Later in the year, they introduced a law requiring unions to separate “mandatory” from “optional” dues, taking a page from Alberta’s playbook.

In Alberta, Premier Danielle Smith’s government went nuclear by invoking the notwithstanding clause to force striking teachers back to the job. Unfortunately, Alberta labour did not follow the lead of CUPE flight attendants. While talk of a general strike proliferated, nothing ultimately materialized.

While flight attendants may have convinced the federal government to think twice about repressing workers’ rights in the near future, clearly many provincial governments remain undeterred. In 2026, unions will need to give governments reason to recalibrate.

The Year Ahead

Over the past year, moments of resistance punctuated a labour landscape that was otherwise quieting down. This doesn’t mean that in 2026 workers can’t again go on the offensive.

Several large contracts expiring at the end 2025 could provide the context for important fights. In November and December, Unifor’s provide-wide agreements with Bell covering around 4,200 workers in Ontario and 1,200 workers in Manitoba expired. SaskPower workers will also be in negotiations.

In the federal public sector, 13,260 Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada members are looking for a new collective agreement, as the federal government sets about a process of workforce adjustment. Workers in the Public Service Alliance of Canada continue to bargain in what will likely prove to be a difficult round of negotiations. Contracts with municipal workers in several Quebec cities, including Montreal and Sherbrooke, are also up for renewal.

Across the private and public sectors, 2026 could prove to be a challenging year for workers and unions. The economy is considerably softer than it was a few years ago. The federal government seems set on a contentious program of austerity. Some provincial governments remain committed to imposing anti-labour laws.

Reversing these trends and building an economy that puts workers first is possible, but only if unions commit to fighting for it. This year is as good a time as ever.

Recent Class Struggle Issues

- December 15 | The Government Is Withholding Data On Labour Relations

- December 8 | Manitoba Workers Will Finally Be Protected From Asbestos

- December 1 | Make Amazon Pay For Its Abhorrent Labour Practices

- November 24 | Trans And Non-Binary Workers Are Worse Off Than Cis Peers