Over the course of the pandemic, the mental health of Canadians has plummeted due in part to a broad range of systemic factors. Yet Bell, one of the most profitable corporations in the country, claims to want to help out.

Every year in late January, people across Canada are subjected to Bell’s “Let’s Talk” campaign, where the corporation promises to donate 5 cents toward mental health organizations for “every applicable text, local or long distance call, tweet or TikTok video using #BellLetsTalk, every Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube view of the Bell Let’s Talk Day video, and every use of the Bell Let’s Talk Facebook frame or Snapchat lens.”

The PR campaign and the inevitable pushback to it have become a staple in the discourse surrounding Canadian mental health. Bell pushes the narrative that they assist in destigmatizing and supporting mental health, and others counter by claiming the company actually doesn’t care. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Critics of Bell often point to allegations that they fired a radio host after she presented mental health leave orders from her doctor, and pushed sales staff so hard that one even puked blood, as proof of their claims. As someone who was in radio for three years, I’ve become well-acquainted with these sorts of stories from people who worked at Bell stations. Bell also charges prisoners for phone calls made from provincial jails, and Bell Media laying off staff right before the holidays has become a sadly predictable phenomenon.

Bell’s hypocrisy is something that surely needs to be pointed out. However, even if all of these stories were false, Bell’s campaign still wouldn’t be a force for good.

To start, the campaign only highlights certain mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress injuries and obsessive compulsive disorder. Meanwhile, other conditions that are even more stigmatized at this point, such as borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia, are mentioned much less. At most, the campaign’s Facebook page may feature people with these conditions, but TV spots and the bulk of other messaging don’t address them at all.

This isn’t to say depression or anxiety have been destigmatized, but rather that there’s a clear priority in what mental illnesses Bell feels are worth shining a light on. The people who suffer from more ostracized conditions are, ironically, too taboo for Bell’s campaign.

The campaign has also failed to adequately account for the unique mental health challenges racialized people face due to systemic racism.

A 2021 study found that the majority of Black people in Canada suffer from “severe depressive symptoms” as a result of systemic racism. Indigenous people are far more likely than other residents in British Columbia to die from opioid overdoses. In fact, toxic drug deaths in First Nations doubled in 2020.

The impact racism has on mental and physical health is dramatic, with experts saying symptoms of depression and PTSD can be directly caused by repeated and continuous racist interactions.

Despite this, it took more than 10 years for Bell’s campaign to commit to something significant directly focusing on this intersection of mental illness, systemic racism and Canada’s genocidal programs. In October 2021, they launched a podcast with racialized hosts to “explore mental health issues affecting culturally diverse communities throughout Canada.” They also promised more funds directly to organizations that help these communities.

And while Bell has donated money to Indigenous programs in the past, they haven’t properly addressed systemic issues in Canada’s healthcare services. But they have certainly evaluated how their campaign benefits corporations.

In her 2019 master’s thesis, Jasmine Vido wrote about how the “Let’s Talk” campaign benefits companies that profit in data-mining, as people who engage with it are targeted by advertisers. Vido writes, “Anti-anxiety blankets, antidepressant vitamins and self-help books are just a few examples of goods that would […] ‘treat’ people who admit they are struggling.” Bell’s campaign gives companies who sell these products more chances at profits. But the products are ineffective, and tackling mental illness properly requires meaningful access to mental health services and resources over a dedicated, long-term period.

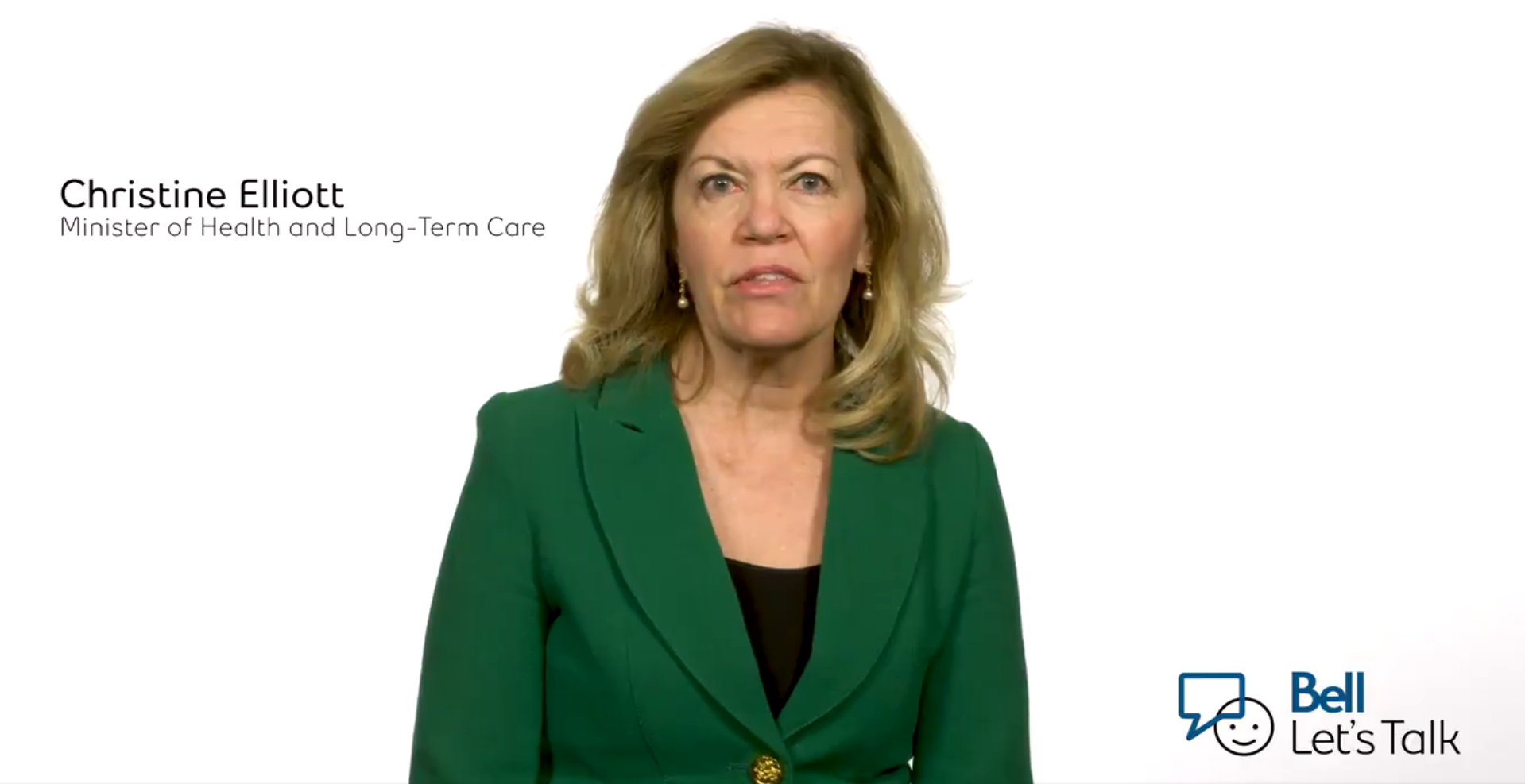

Bell has also used the positive attention it has received from prominent politicians, which grants them institutional legitimization, to excuse alleged abuses. For example, when Bell denied allegations that they pushed their sales people to the brink of mental collapse, a spokesperson said, “Bell has taken a leadership position in workplace mental health. It’s part of the way we work at every level. That’s been recognized by our team, the healthcare community, federal and other levels of government, other corporations across Canada and internationally.”

How dare you criticize Bell’s approach to mental health? Authority figures and institutions have approved of their work, why can’t you?

The campaign has helped change the national discourse toward mental health, but the new approach is also rife with issues. The language of the campaign often focuses on the impact mental health has on the ability of Canadians to work, and this sort of discourse spreads.

For example, a 2016 study from the Conference Board of Canada framed mental health support as a profitable investment, finding that depression and anxiety alone cost the Canadian economy about $50 billion per year. This reduces mental health to a line on a ledger, meaning there’s a good chance support funding will be cut as soon as it’s deemed financially responsible to do so.

Bell’s campaign has also received approval from our political elite. Premiers such as Dennis King, Jason Kenney, Brian Pallister, Doug Ford and Scott Moe have all sent messages of encouragement. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau supports the initiative as well, and even the Canadian Armed Forces joins in. The fact is, however, that these leaders are in a far better position to fund mental health efforts than a private corporation ever could.

Premiers like Kenney praise the efforts of corporations assisting in destigmatizing mental health while cutting funding for health care in their province. Ford will tweet supportive messages, and then stubbornly refuse to implement permanent paid sick days. While the federal government doesn’t have direct control over healthcare, they’ve certainly shown their unwillingness to help.

The focus on Bell’s messaging at the expense of government policies ends up shifting responsibility for the issue onto private entities, who then put the onus on public engagement to raise money and provide free advertising.

Bell is certainly not the company that should be leading the charge in destigmatizing or funding mental health. But the issue goes deeper than a dissonance in actions and words from one corporation.

The issue isn’t specifically Bell, as the dynamics discussed here apply to all corporate charity campaigns. And the only reason Bell has this role is because our governments handed them the torch, ignoring their duties and abandoning Canadians.