Today, people use their political identity and affiliations as a form of catharsis. From SNL’s failed satires of former United States President Donald Trump, to the Babylon Bee recycling the same gender identity jokes from 2015, it’s fair to say that both liberals and conservatives reach for comedic relief by portraying their opponents as stupid and narrow-minded.

Comedic relief isn’t the only goal, however, as the portrayal of an opponent in this way has been a means of reinforcing one’s base. During the 2016 election in the U.S., for instance, Hillary Clinton said, — presumably to a room that already was in some agreement with her — “You could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables,” portraying them as unenlightened and bigoted. In December, Canadian Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole claimed to the Ryerson University Conservative group that “lefty radicals” were the “dumbest people” on campus.

When writing about human neurosis and pride, the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes noted that disagreeing with someone’s politics or religion is sure to sow discord because it’s akin to insulting their intelligence. Today, however, the move to insult the intelligence of an opponent, and to deliberately try to offend them by doing so, comes before the goal of attempting political discourse. It’s not that disagreement inherently sows discord, but that we intend discord by the way that we disagree.

During the Trump presidency, for example, we saw clearly how liberals took delight in mocking his supposed incompetence and mannerisms, while conservatives took equally as much delight ridiculing liberals’ supposed stupidity, sensitivity and naivete.

This mockery, which has come to define much of comedy and satire, serves as a mass therapeutic mechanism, and emerges from a crisis of personal identity and self-esteem.

As the social critic Christopher Lasch wrote in his 1979 book The Culture of Narcissism, “In a society in which the dream of success has been drained of any meaning beyond itself, men have nothing against which to measure their achievements except the achievements of others.”

Success is not only conventionally measured through what one does for a living, which may already lack meaning; it’s also the case that traditional ideals of success we’ve grown up with are increasingly unreachable. Housing is inaccessible, wages have stagnated, college degrees no longer guarantee job security and the proliferation of the gig economy has created a highly precarious workforce. Enjoying a sense of achievement necessitates feeling above others through whatever metric available, and political intelligence is quick and convenient.

With the decline of religion, people lack a community that affirms them and the way they see the world. While religion offered a clear vision of goodness and badness as well as what ought to be embraced and avoided, the secular era — for better or worse — leaves these questions up in the air. The proliferation of online political communities, in turn, create a filler for this void.

These communities also are reinforced outside of the internet and by mainstream media, pop culture and politicians, and offer ideological proxies for people to feel good about their intelligence: ‘You’re logical, because you’re a conservative like us’; ‘You are pro-science, because you’re liberal like us.’ Ideology serves as a proxy for one’s character — you identify with a community to tell others about who you are, and why you’re better than others with a different ideological proxy.

Another important and interesting component of this phenomenon is the false assumption of sincerity.

While Trump was still on Twitter, liberals attempted to angrily argue with him as though his remarks were sincerely unintelligent statements rather than components of a popular political persona. More recently, conservatives gasped at the Taliban calling for an inclusive and representative government. Jordan Peterson, for example, wrote, “This is beyond satire,” ignoring that this wasn’t a sincere statement. The Taliban, as every governing entity seeks to do, is playing a public image and legitimization game while facing feminist delegitimization tactics. This is how politics operates.

Surely Trump reply-guys and popular conservative commentators would both know that political actors don’t make their statements sincerely. Yet, they act with indignation toward them as though that’s the case. They do so because there’s a base that depends on it, and an exchange that occurs through this process. The indignant commentator is showered with approval; a boost to their self-esteem. Their base or community also feels the therapeutic effect of political — and by extension, intellectual — superiority.

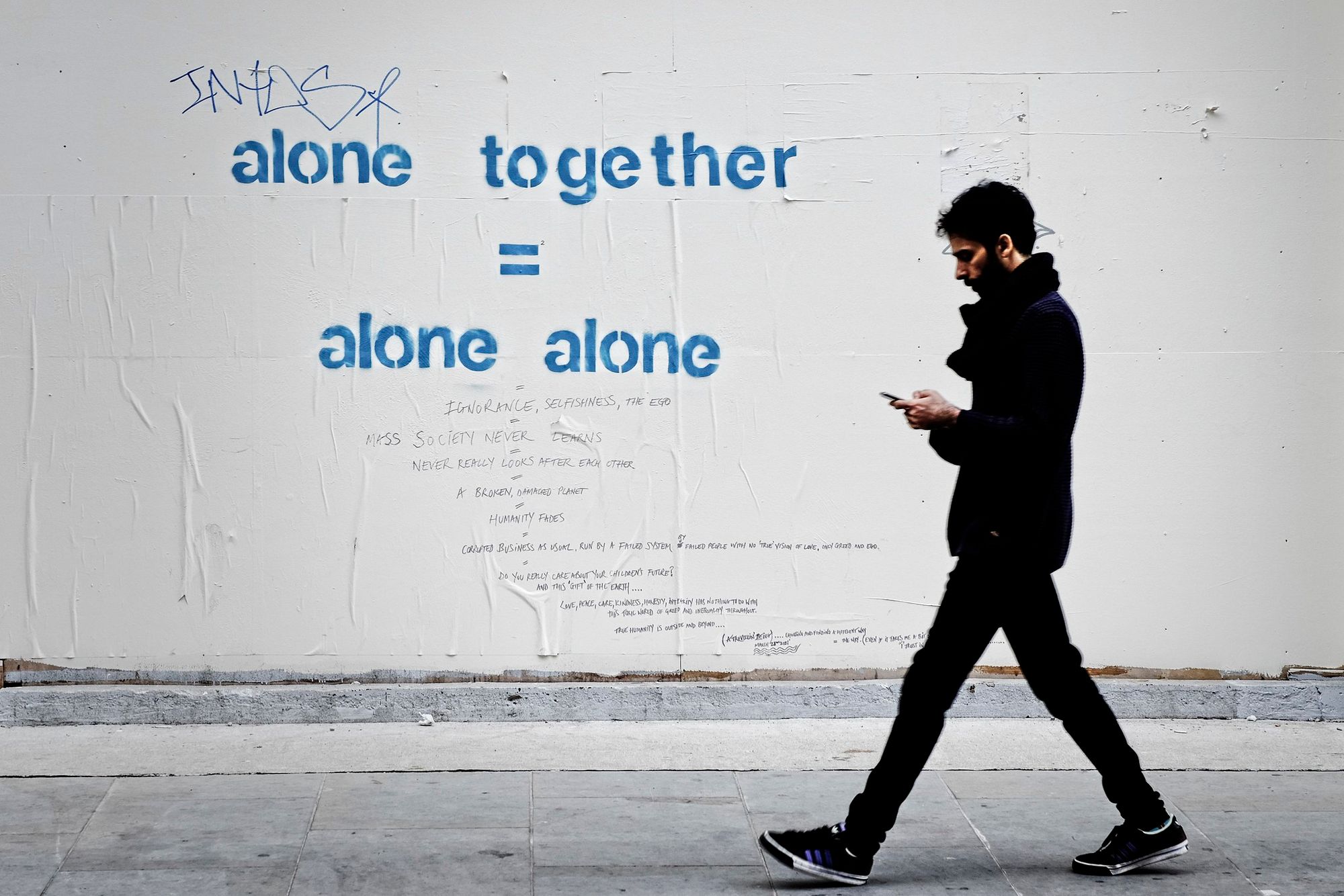

Fundamentally, we’re in a moment where many seem to involve themselves in a political community — left or right — not to try and coordinate for change, but rather to experience a sense of catharsis and belonging. While many have claimed “wokeness” is a religion, it’s more accurate to say that politics in general is serving that function.

I write this because I find this trend to be unsustainable and unhealthy: We’re attempting to compensate for our lack of community and mental health, and then pretending these coping acts are actually meaningful attempts at changing political society, or ones of righteous indignation. In turn, politics becomes obstructed: We’re discouraged from working with people our teams have deemed undesirable or unintelligent, and incentivized to represent other views uncharitably.

Instead of our current course, we ought to be honest with ourselves. What do we seek to gain from political discourse, and from political communities? Are our motives really geared at political change, or are they geared toward feeling intellectually superior and important?

If it’s the latter, we need to reflect on what it is about the way our society is structured that makes this the case, and why we’re unable to derive self-esteem and community from more wholesome and less destructive outlets.

Member discussion