From school closures to child mental health and family stability, the most reported-on facets of COVID-19’s impact on child wellbeing have been negative. However, a surprisingly positive outcome has been that youth detention facilities have far fewer inmates.

Statistics Canada recently published data that shows a dramatic decline in incarcerated youth over the course of the pandemic. The average number of young people in some form of custody (including pre-trial detention and sentenced custody) dropped more than 40 per cent, from 795.2 in 2017-18 to 459.2 in 2021-22.

Fewer youth in custody matters because incarceration, which is often a disorienting and violent experience, removes young people from family, school and other support networks in their communities. Moreover, custody acclimatizes youth to the criminal justice system, making reintegration harder and recidivism more likely.

Indigenous young people are incarcerated at significantly higher rates than other groups in Canada, so youth custody disproportionately impacts Indigenous communities that are already traumatized by the legacy of the residential school system. Ultimately, youth custody has not been found to reduce crime or positively affect young people’s behaviour, and so critics regard subjecting them to incarceration as being mostly about retribution and control.

The recent decrease in incarcerated youth constitutes a significant change in the scope of Canadian youth corrections, and it is part of a much longer downward trend in youth custody that has far reaching implications.

Is this most recent change only temporary? Or could the dramatic reduction of youth prisoners represent a blueprint for decarceration?

The reduction of youth in custody during the pandemic results in part from a broader strategy by courts and correctional systems to decrease the number of incarcerated people as a way to limit contagion.

Prisons, jails and youth facilities are high-density communities, which makes containing a contagious disease liked COVID-19 very difficult.

Moreover, at the height of the pandemic, many institutions were staffed by skeleton crews. High numbers of guards fell sick and isolated at home. And so, Canadian courts and correctional facilities quickly implemented measures like:

“...the temporary or early release of people in custody who are considered at low risk to reoffend; extended periods for parole appeal deadlines and access to medical leave privileges; and alternatives to custody while awaiting trials, sentencing and bail hearings.”

As a result, youth facilities, like their adult counterparts, saw a pronounced decline in inmate numbers.

Other factors related to the pandemic were also at play. Mary Birdsell, executive director of Justice for Children and Youth (JFCY), told The Maple that the introduction of heavy restrictions like lockdowns or curfews across the country meant that fewer people, including youth, were outside of their homes, occasioning fewer encounters with police, fewer arrests, fewer charges and, ultimately, fewer people behind bars.

Birdsell explained that these restrictions likely resulted in less youth crime but also left children and youth vulnerable to abuse at home because they had no access to the normal pathways of support and security that would otherwise be available to them through school, extra-curricular programming, or family and community connections. Youth crime may have dropped, but child and youth victimhood increased.

Nicole Myers, an associate professor of sociology at Queen's University who specializes in criminal justice policy, identified other contributing factors that may have affected youth incarceration rates during this period.

For example, Myers pointed to recent Supreme Court of Canada decisions that made it harder to incarcerate people for breaching their bail conditions. Similarly, Bill C-75, which came into force in June 2019, included amendments that made it more difficult to incarcerate youth who are charged with an administration of justice offence, such as breaching a condition of probation.

As a result of these decisions, fewer people, including youth, may have been incarcerated. And yet, while the above cases and legislative changes may have affected incarceration rates, Myers said that the reduction of youth in custody from 2018 to 2022 was “absolutely related to the pandemic.”

Both Birdsell and Myers agree that the dramatic drop in youth incarceration rates was sudden and significant, but also part of a much longer downward trend in the use of custody to control the behaviour of young people in Canada. This trend was the clear result of legislation called the Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA), which became law in 2003.

Before the YCJA, explained Birdsell, Canada incarcerated more youth than any other Western country. Texas was the only jurisdiction that confined more young people per capita than Canada, although Saskatchewan and Manitoba posted higher rates of youth in custody than Texas.

Substantial numbers of young people in Canada were in jail for minor offences, like breaches of curfew. And many social service-related issues were managed by youth custody. If a young person was unhoused, for example, they could be incarcerated.

As a result, Canada’s youth justice system, which was then regulated by the Young Offenders Act (YOA), was overloaded, and many young people were in custody with no purpose being there.

Richard Barnhorst, who was part of a small team of lawyers with the Department of Justice that developed the policy and the specific legislative provisions that became the YCJA, explained that the Act was “a complete shift in youth justice philosophy.” It took seriously the belief that there should be greater restraint in the criminal justice system.

Many of the changes in the youth justice system under the Act, Barnhorst observed, were “astounding.” Most notably, youth custodial sentences decreased by 91 per cent since 2003. “I’m not sure many people realize [the Act’s significance],” Barnhorst added.

In 2002, the year before the YCJA was implemented, an average of 4,145.5 youth were in custody. Five years later, 2,008.3 youth were in custody.

Another five years after that, 1,370.4 youth were in custody. And the numbers continued to drop every year. As noted above, by 2018, the number of incarcerated youth dropped to under 800.

Did the reduction of youth in custody result in an increase in youth crime during that period?

Not at all. Statistics Canada figures show that, from 2003 to 2021, the youth crime rate dropped by 72 per cent; youth crime severity declined by 65 per cent; violent youth crime severity decreased by 30.7 per cent, and non-violent crime dropped by 78.7 per cent.

However, Barnhorst stressed that the reduction in youth crime is not to be interpreted as an effect of the YCJA. But, it demonstrates that the decarceration of youth over the past 20 years has not made youth crime worse.

Understanding the effects of the longer downward trend in the number of incarcerated young people in Canada helps to determine some of the potential risks of the more recent, sudden and rapid drop in those numbers.

Importantly, less youth in custody has resulted in the closure of many regional facilities and the centralization of youth carceral institutions, some of which remain open but unfilled.

Birdsell noted that losing regional facilities means that young people are often removed from their communities, families and personal connections. In some cases, distance from a toxic environment can be a good thing, but typically, removing a young person from their community to serve time in an alien environment is isolating and potentially damaging.

The removal of Indigenous youth from their communities is especially troubling and constitutes a significant problem for the youth custody system. Indigenous youth are overrepresented in youth custody, and many Indigenous young people live in communities at a great distance from youth custody facilities.

In 2021, when Ontario Premier Doug Ford abruptly closed 26 youth detention facilities, which constituted half of all facilities across the province, Grand Chiefs representing Nishnawbe Aski Nation and Grand Council Treaty 3 wrote an open letter to the premier expressing their “collective horror about the impact on youth, from northern First Nations in particular, resulting from the abrupt closure of these facilities.” The sudden drop in youth incarceration over the pandemic exacerbates these and other problems that have already strained the system.

Birdsell suggests alleviating these problems by increasing support services to local communities and shifting youth custody from larger centralized institutions to smaller, community-centred facilities.

Smaller, localized facilities have been identified for some time as more effective options for youth corrections. For example, a panel convened by the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services noted in their 2016 report:

“There is some indication that the size of the facility contributes to a youth-centred, therapeutic focus and the ability to establish positive relationships with young people, with smaller facilities often more able to accomplish these objectives.”

Despite warnings from specialists that smaller, regional facilities better serve youth corrections, federal and provincial governments have been slow to react. In the case of the Ford government, they went in the opposite direction.

Notwithstanding these concerns, Myers said the recent reduction in the number of young people in custody in Canada is a promising sign, particularly when viewed in relation to longstanding trends.

“Look what’s possible,” said Myers. The drop in the number of young people in custody during the pandemic "suggests we are over-using custody in the first place."

Simon Rolston lives in Vancouver, and he writes about criminal justice issues, particularly the Canadian and U.S. prison systems. His book, Prison Life Writing: Conversion and the Literary Roots of the U.S. Prison System, was recently published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Go deeper

Here are a few stories from that expand on today's article

How To Dismantle The Prison Industrial Complex

From Passage: Abolishing prisons may seem like a radical idea to many, but there’s a strong, practical case to be made for it. In this course, Ted Rutland and Virginia Adamczak look at the history of Canada’s prison industrial complex, outline the immense harms it causes, and explore strategies for dismantling it and creating alternatives that promote safer and healthier communities.

More COVID Outbreaks Reported In Jails As Advocates Raise Concerns About Prisoner Safety

From January 2022: A series of COVID-19 outbreaks were reported at jails across the country as prisoners’ rights advocates express concerns about protecting inmates who are at risk of falling sick.

Top Maple story this week

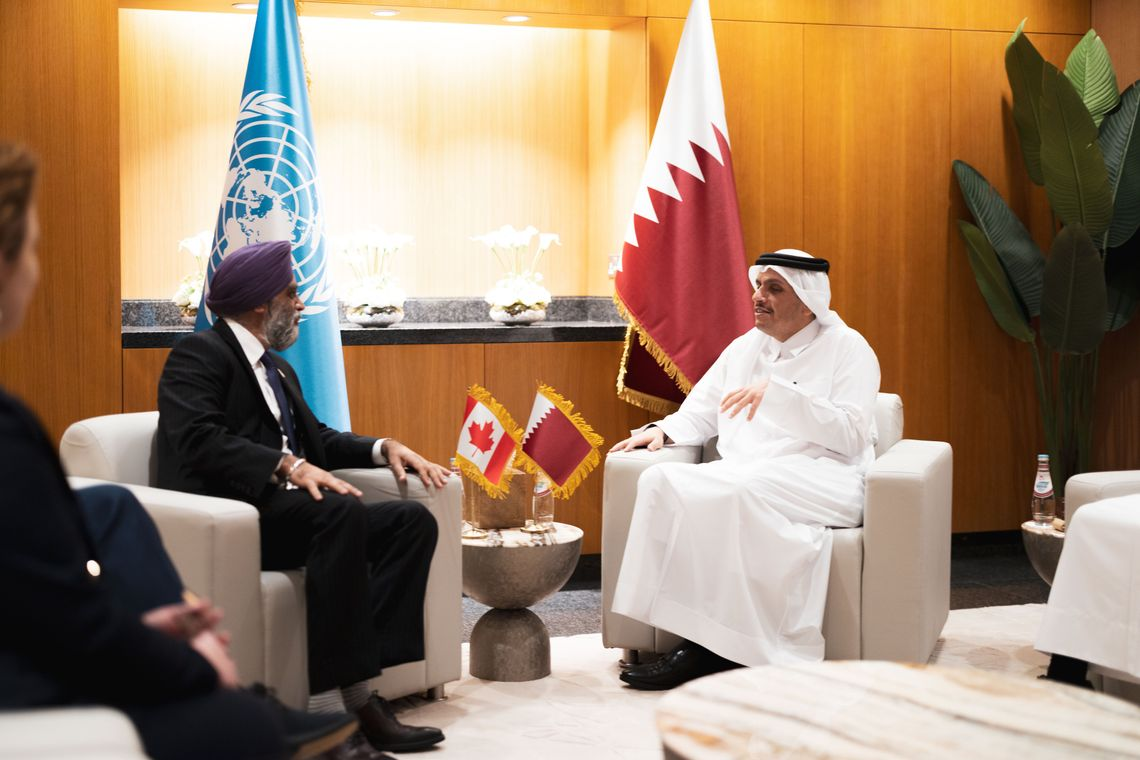

Minister Lobbied Qatar For Light-Armoured Vehicle Deal At World Cup

Ahead of a meeting with Qatar’s minister of foreign affairs at the FIFA World Cup last year, International Development Minister Harjit Sajjan was briefed to lobby for a potential deal between a Canadian light-armoured vehicle (LAV) supplier and the Qatari military.

Catch up on our latest stories

- Grocery Rebate Pays Just $9 Per Week For A Family Of Four.

- The Dark History of Psychological Coercion at McGill.

- Conservative Poll Lead Shrinks To Lowest Margin Since Last August.

Before You Go

We rely on the support of our readers to help us grow. If you support this type of journalism, here are some ways you can help…

🙏 Our work is funded entirely by readers like you. Become a member and help keep our journalism alive.

📣 Share The Maple on Facebook or Twitter and help us spread the word!

💵 Make a one-time donation to our Freelancer Fund and help us commission the top Canadian journalists.

📫 Sharing is caring - forward this newsletter to a friend and encourage them to subscribe today! (Hint: you can sign up here).

🎧 Prefer listening to your news? Check out our podcast here.