Since the end of the Cold War, Canada’s peacekeeping operations, although never particularly peaceful, have taken a more explicitly violent turn — especially across Africa and the Caribbean.

Through the 1990s and into the 2000s, Canadian and United Nations officials began expanding their power to use force and launch interventions without the consent of those living in the affected areas.

Even looser constraints

Prior to the 1990s, writes Jocelyn Coulon, who was previously Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s foreign affairs advisor, the majority of Canada’s peacekeeping operations were conducted according to Chapter VI of the United Nations charter, meaning they were based on the consent of parties, impartiality and the minimal use of force for self defence.

In reality, Canadian peacekeepers during this period directly killed no small number of people in the countries in which they intervened. Just as often, the peacekeepers worked in tandem with invading armies.

While these past missions generally began with consent from the host countries (as in Egypt, Congo and elsewhere), once the peacekeepers entered, getting them to leave often proved to be difficult.

Since the early 1990s, even these already flimsy checks have been dramatically revised in favour of more violent and forceful interventions.

‘An agenda for peace’: Expanding the use of force

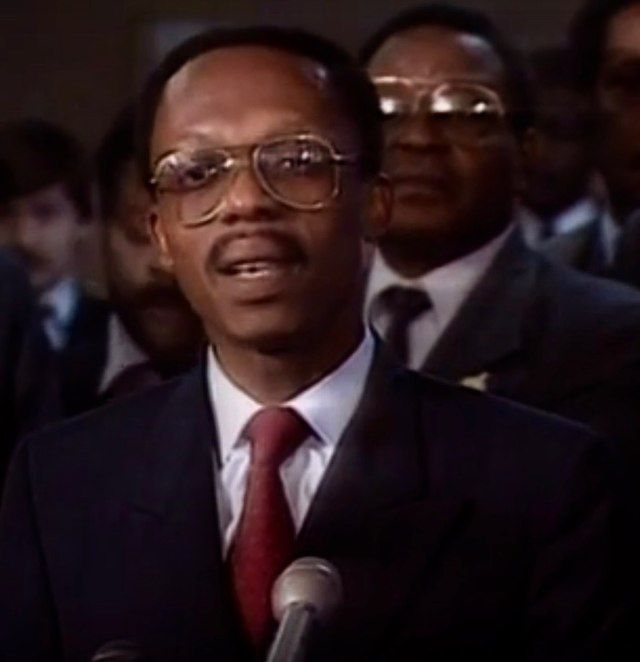

In June 1992, United Nations secretary general Boutros Boutros-Ghali remarked that the basic marketing terms of traditional peacekeeping – such as the “consent” of the host and the minimal use of force – had to be qualified.

Already, in 1973, then-secretary general Kurt Waldheim had clarified that the right of peacekeepers to use force in self defence in practice meant allowing "resistance to attempts by forceful means to prevent [them] from discharging [their] duties under the mandate of the Security Council."

Boutros-Ghali, for his part, acknowledged that "existing rules of engagement allow [United Nations soldiers to open fire] if armed persons attempt by force to prevent them from carrying out their orders." Still, in his speech “An Agenda For Peace,” the secretary general insisted that allowances for the use of force needed to be expanded.

With advice from Canadian military general Maurice Baril, Boutros-Ghali proposed that peacekeepers become, as Coulon put it, “more active, even more aggressive in the field.”

“The time of absolute and exclusive sovereignty,” Boutros-Ghali declared in 1992, “has passed.” He acknowledged that “its theory was never matched by reality.”

Soon after, as the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) observed in a 2002 report, the UN Security Council reiterated its readiness to take “appropriate measures” against parties which did not observe its decisions, and to authorize “all means necessary for United Nations forces to carry out their mandate.”

In the long term, Boutros-Ghali would be marked by, as Coulon notes, having “asked NATO to prepare a plan for the use of air power” in the breakup of Yugoslavia, as well as for his support for increasingly belligerent peacekeeping operations.

In the lead up to NATO’s first air strikes in Sarajevo, UN spokesman Fred Eckhard acknowledged to the Associated Press that expanding the enforcement of a no-fly zone over the region to a bombing campaign “would put at risk a large number of unarmed civilians” involved in other UN operations, and increase the intensity of the civil war.

It would, Eckhard warned, risk “Yugoslavia becoming another Somalia.”

Torture and murder in Somalia

On Jan. 26 1991, Siad Barre’s once Soviet-supported government in Somalia collapsed, and the country descended into civil war. As the Islamist United Somali Congress advanced on the country’s capital of Mogadishu, further violence between armed factions ensued.

On Apr. 24, 1992, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 751, establishing a small contingent of peacekeeping troops to intervene, seemingly without the consent of any Somalians.

Operation Deliverance saw Canadian “peacekeepers” – including, infamously, the Airborne Regiment – join the United Nations Operation. Initially, that mission tasked the peacekeepers with ensuring the delivery of humanitarian supplies to Mogadishu, and then to maintain order between warring “Somali factions.”

After a false start in the relatively peaceful zone of Boosaaso, the peacekeepers were re-deployed by U.S. strategic planners at the request of Canada’s then-chief of defence staff John de Chastelain.

Stationed in the city of Beledweyne, the Canadian peacekeepers secured roads for aid transfers. But they and other peacekeepers also clashed with local militias.

In December, the UN Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 794 to create a U.S.-led Unified Task Force (UNITAF), transforming the mission into a “Chapter VII” operation. With this change, the peacekeepers were allowed to use “all necessary means” to establish a “secure environment for humanitarian relief operations.”

After another round of clashes, the mandate was expanded again. UNSC Resolution 814, in March 1993, meant the peacekeepers were, as University of Toronto international security professor Aisha Ahmad writes: “Mandated to pacify and disarm combatants, restore law and order, continue humanitarian relief operations, support a political settlement between the factions and rehabilitate domestic political institutions.”

This, as Coulon notes, came with some immediate confusion around the rules of engagement. For example, the peacekeepers “were not authorized to use tear gas to control crowds; the Canadian and other Blue Helmets had to use their weapons [to] neutraliz[e] troublemakers.”

Indeed, the subsequently court-martialled captain Paul William Hope noted he did not review the UN Charter ahead of the deployment, and said he considered it “a straight military operation.”

But other Canadian peacekeepers did appear to closely observe the law. Lt. Col. Carol Mathieu, one of the few implicated in what came to be known as the “Somalia Affair” to give a testimony on the scandal, ordered that any theft of aid and supplies be considered an act of “sabotage” – which, Ahmad notes, allowed Canadian troops to “use deadly force against suspected thieves.”

The regiment was, as it later emerged, also sent by Sgt. J.K. Hillier to capture “infiltrators” as a “demonstration of Commando vigilance and intolerance of infiltrators.”

The resulting scandal is well-remembered.

On March 4, 1993, led by Cpt. Michel Rainville, the Canadian peacekeepers laid out food and water as bait. They captured and shot two unarmed teenagers, Ahmed Arush and Abdi Hunde Bei Sabrie.

On March 16, 1993, Captain Michael Sox captured 16-year old Shidane Abukar Arone, a suspected “looter” hiding in a portable toilet near an abandoned American air base. Less than 24 hours later, multiple accounts claimed, he was kicked, waterboarded, sodomized, burned, beaten with a baton and ultimately killed.

Ahmad writes that the killing of Shidane Abukar Arone was ignored by nearby soldiers, who “deemed the mistreatment of detainees appropriate as earlier that day Captain Sox had passed down orders from commanding officer Major Anthony Seward to ‘capture and abuse the prisoners.’”

In his diary, Seward affirmed that he did “order Somali intruders to be abused during the conduct of apprehension and arrest.’”

Shortly after the scandal emerged, it was revealed that Canadian peacekeeper Cpl. Matt McKay, then serving in Somalia, had previously sported Nazi regalia while serving in the military. Defence minister Kim Campbell accepted explanations that this was merely a “youthful folly.”

Later, a federal inquiry stated that “wavering” by the UN secretary general meant the operation was at times stuck in a “grey area between peacekeeping and low-intensity war.”

The emergence of ‘Chapter VII’ peacekeeping

While the Airborne Regiment was disbanded after the Somalia torture scandal, and the absolute abrogation of “consent” was put on hold, the expansion of peacekeepers’ use of force would persist.

Since 1992, in place of “Chapter VI” or “classical” peacekeeping, Chapter VII peacekeeping – where peacekeepers are freer to use force beyond self defence and defence of their mandate – has become dominant.

In 2017, the UN itself declared: “The era of ‘Chapter VI-style’ peacekeeping is over.” A 2019 parliamentary report noted that Canada’s peacekeepers have been increasingly empowered to use force “not only in self-defence, but also to protect civilians and to counter threats.”

In Soldiers of Diplomacy, Coulon writes:

“Between 1988 and 1994, taking advantage of the end of the Cold War and the alignment of the Soviet Union with Western Positions, the UN established twenty peacekeeping missions, of which only half a dozen were of the traditional type … The UN decided to make more frequent use of Chapter VII of its charter, which authorizes the use of force to fulfill UN mandates or to restore international peace and security.”

Swarthmore College political sciences professor Emily Paddon Rhoads likewise observes:

“Since 1999, blue helmets in places such as Sierra Leone, Haiti, Ivory Coast, and Mali have conducted military offensives to ‘keep’ and ‘make’ peace. Once limited in scope and based firmly on the consent of all parties, peacekeeping operations are now regularly authorized under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, charged with penalizing spoilers of the peace and protecting civilians.”

More recently, legal scholars, United Nations officials and others have distinguished between Chapter VI peacekeeping and “peace enforcement” missions, which are based on Chapter VII. But the difference, as noted by the 2002 SIPRI report, between Chapter VII “peacekeeping” in particular and “peace enforcement” is in significant part “semantic.” The report observed:

“The situation has been complicated since the end of the cold war by the tendency of the Security Council to afford Chapter VII mandates to what have been perceived essentially as peacekeeping operations.”

Sierra Leone

“Africa Burns, Canada fiddles,” declared a Globe and Mail headline in March 1999. While “Canadian companies have invested more than $100 million in the region in the past year,” the paper lamented, it had suffered from the “withdrawal of United Nations peacekeepers.”

Sierra Leone, well known for its vast mineral deposits, was a priority for the Canadian government and other NATO powers. At the time, the country’s civil war had, according to the Globe, descended from a military coup into reports of mass killings, mutilations and rapes.

The situation was not helped by Canadian mining companies. In particular, three Canadian mining giants — Diamond Works Ltd., Rex Diamonds Mining Corporation and AmCam Minerals — were accused by the federal government in 2000 of providing money and other assistance to dump military equipment and mercenaries into the war zone.

A 1997 report, for example, stated that a company controlled by Diamond Works had helped bring in a mercenary outfit, headed by personnel from South Africa’s apartheid-era special forces units, under orders from a Sierra Leone military commander to “kill everybody.”

The other side in the war, the RUF militia founded by Foday Sankoh, was also funded and armed with foreign money — notably by former Ukrainian timber magnate Leonid Minin.

Asked about the proliferation of mercenaries, a former UN peacekeeping officer told the Ottawa Citizen they may just have to be tolerated: “In a perfect world we don’t need them or want them. But the world isn’t perfect.”

This was supported by, among others, Britain’s foreign secretary Jack Straw, who declared: "A strong and reputable private military sector might have a role in enabling the UN to respond more rapidly and effectively to crises.”

The UN pushed ahead for a forceful intervention inside the country.

“It’s a dirty, messy business,” then-foreign affairs minister Lloyd Axworthy declared to the United Nations in 1999. “Something has to be done.”

From a previous observer mission, Canadian officials told the Globe they had pushed immediately to apply a Chapter VII mandate, arguing to “‘go in strong’ with a robust mandate and the resources to match, and be prepared to scale back should circumstances on the ground warrant.”

The UN Security Council soon followed through, re-establishing the UNAMSIL peacekeeping force — now consisting of 6,000 military personnel with a Chapter VII mandate, and tasked with, among other things, “disarm[ing] belligerents.”

Ethiopia, Eritrea and the ‘high readiness military tool’

In September 2000, hundreds of UN peacekeepers – including “armoured reconnaissance” and a “mechanized infantry” – were dispatched to the border of Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Under a Chapter VI mandate, the peacekeepers made up part of the UN’s later shuttered Standby High-Readiness Brigade, a force developed in part by Canadian officials for faster, six-month deployments. Taking advantage of a decline in Security Council vetoes, one 1995 Canadian military document proposed that the standing force could act as “the sharp end of future UN action.”

Initially, the Canadian forces wanted a short operation along the border, because, according to the Globe, such an operation “ensures that combat-ready troops are always standing by.”

While defence minister Art Eggleton said it would not be a “front-line or offensive combat operation” on the ground, open war took place anyway. "This war was almost like a throw-back to the First World War where the front lines were only about 100 yards apart,” Maj. Don Rees recalled.

In 2005, when Eritrea demanded that the Canadian troops leave, Jean-Marie Guehenno, the UN undersecretary-general for peacekeeping, said the issue would be referred to the UN Security Council. He remarked: "Certainly we are not planning to pull out any of the people who have been mentioned."

The Canadian peacekeepers remained in the region until 2008.

‘Complex peacekeeping’ in Haiti

UN peacekeepers have intervened repeatedly in Haiti since a popular uprising toppled Jean-Claude Duvalier’s right-wing dictatorship in 1986 — forcing him to flee to France on a U.S. Air Force plane.

When Lavalas leader Jean-Bertrand Aristide returned to power, after being ousted in a 1991 military coup, his repeated re-election wins infuriated a belligerent right-wing opposition, which eventually organized into Convergence Démocratique (CD).

The leadership of CD, for its part, was very clear to the Washington Post that it hoped for the U.S. military to directly “get rid of Aristide and rebuild the disbanded Haitian army” or, alternatively, for the CIA to “train and equip Haitian officers” who were in exile since the end of Duvalier’s regime.

As the rightwing prepared an insurgency, the Washington Post declared, Aristide faced “increasing pressure from the United States and other governments to leave office.”

Canada was one of those “other governments.”

In early 2003, Denis Paradis, Canada's secretary of state for Latin America and La Francophonie, hosted roundtable meetings dubbed "The Ottawa Initiative on Haiti.” While no representatives from Haiti’s government were present, the meeting still – according to one account – eagerly discussed the “possibility” of Aristide’s “departure” with Otto Reich and others implicated in past coups across Latin America and the Caribbean.

“Situation[s] like Haiti,” Paradis argued, “don't exclude the military taking over a country where the state failed to protect its people.”

Since 1996, Canada’s various peacekeeping forces had been buttressed by Joint Task Force (JTF) commandos to help train the country’s SWAT units. They returned to Haiti in 2004, soon after their deployment to Afghanistan, to act as an “assault troop” in the midst of the unrest.

According to the American Forces Press Service, Canada dispatched “a team of JTF2 [Joint Task Force 2] commandos” to protect “Canadian assets and secure the International airport,” while Aristide was flown out.

After Aristide’s removal, CNN reported: “A small contingent of Canadian troops [was] already in the city.”

“We are waiting for the international force,” rebel leader Guy Philippe told CNN. “They will have our full cooperation.”

Soon after Aristide’s departure, Canada deployed an additional rifle company and tactical helicopters as part of a larger UN Multinational Interim Force (MIF).

The Canadian forces followed a UN directive to coordinate on building a “secure and stable environment in Haiti” with a Chapter VII mandate to use “all necessary means” to do so. This was expanded in June 2004, based upon UN Security Council Resolution 1542 to aid the “transitional government.”

Reviewing the events, Colonel Fred A. Lewis wrote that Canada’s “successful” interventions in Yugoslavia, Somalia and Haiti marked a new form of “complex peacekeeping.” This is described elsewhere by Canadian army officials as operations which did not “benefit” from the “full consent of the parties and at times mandated, and used, force beyond self-defence.”

Putting it differently, University of Ottawa global studies professor Stephen Baranyi writes: “There is no doubt that grave human rights violations were committed both by [UN peacekeepers] and by the [Haitian National Police] during the grim years of 2004-2005.” According to first-hand accounts at the time, these attacks were against gangs and identified “Aristide supporters” alike.

A report by Harvard University Law Student Advocates for Human Rights found:

"MINUSTAH's most visible efforts have involved providing logistical support to police operations, which ... are implicated in human rights abuses, such as arbitrary arrest and detention and extra-judicial killings."

Even while defending the mission, Robert Fatton Jr. likewise conceded: “MINUSTAH has occasionally used dubious methods of repression.”

Col. Jacques Morneau remarked that “The HNPS had lost the confidence of the general population; it is not an exaggeration to say it is hated by some sectors of society.” Morneau observed that in the slums of Cité Soleil, there is a “reluctance and often refusal to patrol the slums on foot, patrolling instead in armoured personnel carriers on the main streets only.”

Noting that the area consists “mostly of slums,” Morneau suggested “close air support” to “neutralize snipers on roofs, towers and hills.”

Major General Michael T. Ward, then the director of learning design and program support for the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, went further, proposing long-term “international trusteeship.” In his 2006 article, Ward suggested overriding the UN’s “commitment to …sovereignty [and] independence” and obligations to “hold elections at the earliest possible date.”

Ward, a former NATO training official, wrote: “Elections should not be held before they can be carried out in a sufficiently institutionalized and effective framework. The Haitian people must have had time to internalize the norms that surround these acts.”

He called for global powers to maintain long-term “stabilization” operations to establish a new political and “economic” culture – a long-term military occupation.

‘Robust international peacekeeping operations’

The end of the Cold War, Brigadier Lamont Kirkland told a 2004 NATO conference, called for “robust” peacekeeping methods. He explained that “operations will be more complex and multidimensional; it recommends that a fresh approach be taken to prepare for and execute alliance operations.”

Similarly, the federal government’s 2005 International Policy Statement conceded that since the end of the Cold War: “Most of the Canadian Forces’ major operations have borne no resemblance to the traditional peacekeeping model of lightly armed observers supervising a negotiated ceasefire.”

Land Operations’ 2008 draft “Counterinsurgency Manual,” released by Wikileaks, further blurred the lines between war tactics and peacekeeping. It listed Canadian deployments in Afghanistan and Haiti alike as recent counterinsurgency operations, demonstrating how the greatest “attrition of insurgents” can be achieved with artillery and “precision strikes.”

Current Chief of Defence Staff Wayne Eyre himself proposed a major overhaul of combat and “peacekeeping” operations alike in 2006.

In a widely cited military journal article, Eyre reviewed Canada’s ill-defined peacekeeping operations throughout the 1990s. In Yugoslavia and elsewhere, he argued, peacekeeping descended into war and “only the unit’s inherent combat capabilities allowed for mission success.”

In all cases, Eyre insisted:

“The lesson we must take away is that, regardless of the mission’s mandate, our troops have to be able to fight and win. Only the mindset of a professional soldier who is trained and psychologically ready to kill the enemy, whoever that may be, will be the saviour when a mission goes downhill.”

Go deeper

Here are a few stories from our archive that expand on today's story.

Canada’s Modern Day ‘Peacekeeping’ Is War-making by Another Name

In this article, we examine the shift from early “peacekeeping” to overt war-making.

The Bloody History of Canadian ‘Peacekeeping’

Canadian Liberals have long celebrated this country’s history of “peacekeeping” as one characterized by upholding a benign and humane alternative to war. But in reality, the difference between war and “peacekeeping” is hazy.

Top Maple story this week

Understanding Canada’s Muted Response to Israel’s Recent Attacks on Gaza

On the most recent episode of The Maple’s North Untapped podcast, we spoke to Michael Bueckert, vice president of Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East (CJPME), about Israel's recent attacks on Gaza and what CJPME views as the Canadian government's “non-response” to those attacks.

Download the full episode to hear this informative discussion on Apple,Spotify or Google, and help us reach an even bigger audience by leaving us a five-star review on Apple podcasts!

Catch up on our latest stories

- Interview: Anjali Appadurai’s Challenge to the Status Quo

- Interview: The Next Premier of British Columbia?

- Canadian Government Called Out Over Response to Israel’s Latest Attack on Gaza.